|

|

|

01 |

Sunday morning |

|

|

|

02:56 |

|

|

02 |

I'm waiting for the man |

|

|

|

04:39 |

|

|

03 |

Femme Fatale |

|

|

|

02:38 |

|

|

04 |

Venus in furs |

|

|

|

05:12 |

|

|

05 |

Run run run |

|

|

|

04:22 |

|

|

06 |

All tomorrow's parties |

|

|

|

06:00 |

|

|

07 |

Heroin |

|

|

|

07:12 |

|

|

08 |

There she goes again |

|

|

|

02:41 |

|

|

09 |

I'll be your mirror |

|

|

|

02:14 |

|

|

10 |

The black angel's death song |

|

|

|

03:11 |

|

|

11 |

European son |

|

|

|

07:48 |

|

|

|

| Country |

USA |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

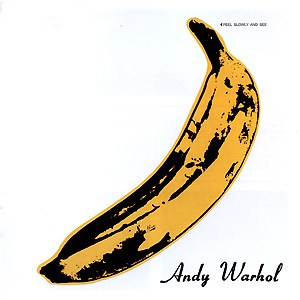

The Velvet Underground & Nico

Date of Release Jan 1967

One would be hard pressed to name a rock album whose influence has been as broad and pervasive as The Velvet Underground and Nico. While it reportedly took over a decade for the album's sales to crack six figures, glam, punk, new wave, goth, noise, and nearly every other left-of-center rock movement owes an audible debt to this set. While The Velvet Underground had as distinctive a sound as any band, what's most surprising about this album is its diversity. Here, the Velvets dipped their toes into dreamy pop ("Sunday Morning"), tough garage rock ("Waiting for the Man"), stripped-down R&B ("There She Goes Again"), and understated love songs ("I'll Be Your Mirror") when they weren't busy creating sounds without pop precedent. Lou Reed's lyrical exploration of drugs and kinky sex (then risky stuff in film and literature, let alone "teen music") always received the most press attention, but the music Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Maureen Tucker played was as radical as the words they accompanied. The bracing discord of "European Son," the troubling beauty of "All Tomorrow's Parties," and the expressive dynamics of "Heroin," all remain as compelling as the day they were recorded. While the significance of Nico's contributions have been debated over the years, she meshes with the band's outlook in that she hardly sounds like a typical rock vocalist, and if Andy Warhol's presence as producer was primarily a matter of signing the checks, his notoriety allowed The Velvet Underground to record their material without compromise, which would have been impossible under most other circumstances. Few rock albums are as important as The Velvet Underground and Nico, and fewer still have lost so little of their power to surprise and intrigue more than 30 years after first hitting the racks. - Mark Deming

1. Sunday Morning (Cale/Reed) - 2:56

2. I'm Waiting for the Man (Reed) - 4:39

3. Femme Fatale (Reed) - 2:38

4. Venus in Furs (Reed) - 5:12

5. Run Run Run (Reed) - 4:22

6. All Tomorrow's Parties (Reed) - 6:00

7. Heroin (Reed) - 7:12

8. There She Goes Again (Reed) - 2:41

9. I'll Be Your Mirror (Reed) - 2:14

10. The Black Angel's Death Song (Cale/Reed) - 3:11

11. European Son (Cale/Morrison/Reed/Tucker) - 7:46

John Cale - Bass, Piano, Guitar (Bass), Keyboards, Viola, Viola (Electric)

Nico - Vocals, Chant

Lou Reed - Guitar, Guitar (Electric), Keyboards, Vocals

Maureen Tucker - Bass, Percussion, Drums

The Velvet Underground - Arranger

David Greene - Editing, Remixing, Remastering

Hugo - Photography

Bob Ludwig - Mastering

Sterling Morrison - Bass, Guitar, Guitar (Bass), Guitar (Rhythm)

Gene Radice - Editing, Remixing, Remastering

Val Valentin - Director of Engineering

Andy Warhol - Producer, Design, Cover Painting

Tom Wilson - Producer, Editorial Supervisor

Omi Haden - Engineer

Acy Lehman - Cover Design

Nat Finkelstein - Photography

John Wilcock - Liner Notes

Billy Linich - Photography

CD Verve 823290-2

1967 LP Verve V6-5008

1997 CD Mobile Fidelity 695

1990 CD Verve 823290

CS Verve 823290-4

2000 CD Polygram International 9001

1996 CD Verve 531250

1996 CS Verve 531250

2002 CD Polygram International 9134

I'm Waiting for the Man

Composed By Lou Reed

AMG REVIEW: The Velvet Underground's most famous (or infamous) song, "Heroin," displayed a laissez-faire attitude about drug use that was scandalous in 1966, but while that song portrayed the troubling lure of narcotics at face value, "I'm Waiting for the Man" confronted an even stickier issue - the day-to-day realities of addiction. "I'm Waiting for the Man" hardly makes being a junkie sound like fun; feeling "sick and dirty/more dead than alive," the song's protagonist heads to a rough neighborhood uptown, where he's uncomfortably conspicuous as the only white guy around. His dealer, of course, doesn't show up on time (he apparently never does), and he becomes more and more nervous until he's able to score his 26 dollars worth of dope, shoot up, and wait for the process to start over again. While the details hardly sound inviting, the sneering cool of Lou Reed's vocal and the blotted-out bliss of the line "I'm feeling good/You know I'm gonna work it on out" might make some wonder if the thrill of the rush is worth the agony of the other 1,430 minutes of the day. In the song's original recording on the album The Velvet Underground and Nico, "I'm Waiting for the Man" had a frantic, staccato rhythm, nailed down by John Cale's hammering piano riffs. After Cale left the group and his keyboard left the arrangement, Maureen Tucker's drumming gained a bit more of a swing, and the tune took on a sturdy groove, as evidenced in a recording from Dallas, TX, featured on 1969 Velvet Underground Live (as well as the bootleg The End of Cole Avenue). In 1984, Cale took up the song again in his live shows, and his stark rendition appeared on the live set John Cale Comes Alive. Finally, in 1993, as the Velvet Underground mounted a reunion tour of Europe, the song found its way into their set once again - and in a surprising gesture, Lou Reed deferred to John Cale's version of the song and let Cale take the lead vocal. - Mark Deming

Venus in Furs

Composed By Lou Reed

AMG REVIEW: One of the most distinctive songs on the first Velvet Underground album, "Venus in Furs" is a haunting, ethereal viola-led paean to S & M, powered by funeral drums and Lou Reed's most sneeringly disinterested monotone - even weird sex has seldom sounded so cold and calculated although, as guitarist Sterling Morrison pointed out, "musically it's so shocking, it could have been about anything. That's what frightened people." Reed himself continued, "the prosaic truth about "Venus in Furs" is that I'd just read this book by Sacher-Masoch, and I thought it would make a great song title, so I had to write a song to go with it." He denied, however, that it was at all autobiographical. "It's not necessarily what I'm into." Alongside "There She Goes Again" and "Heroin," "Venus in Furs" was one of the three songs played at the Velvet Underground's first ever gig, at Summit High School on November 11, 1965. However, when the band began shopping around for a record deal, at least one record label ( Atlantic) insisted that "Venus in Furs" be dropped from the repertoire before they'd even consider signing the band, while another ( Elektra) demanded that the band dispense with the viola - which amounted to much the same thing. Thankfully Verve, the band's eventual home, were less squeamish, although a version of "Venus in Furs" without the viola does exist on bootleg, recorded at Poor Richards in Chicago, with Cale taking over lead vocals from the absent (through illness) Reed. - Dave Thompson

All Tomorrow's Parties

Composed By Lou Reed

AMG REVIEW: One of three songs sung by Nico on the first Velvet Underground album, "All Tomorrow's Parties" would remain in her live set for much of her solo career - indeed, although the song is frequently described among Lou Reed's finest compositions, it is difficult to even imagine it being sung by anyone else. (That said, a number of covers have emerged over the years, including a fine rendering by Nick Cave.) Edited down from its near-six-minute entirety to become the Velvet Underground's first ever single, the actual performance is not among the band's best. Nico sounds terrific, commanding all that lies before her; the musicians, however, all but cower in her shadow, restricting their involvement to little more than fluttering guitar and sepulchral drum. In later years, Nico would take to performing the song a cappella - not a fate that one normally expects to greet a Velvet Underground song but, on this occasion, a wise one. - Dave Thompson

Heroin

Composed By Lou Reed

AMG REVIEW: In 1966, when the Byrds' "Eight Miles High" and Bob Dylan's "Rainy Day Women #12 and 35" were generating no small controversy for daring to flirt with the subject of recreation drug use, the Velvet Underground crossed a then-unthinkable threshold and began performing a song called "Heroin." Actually, Lou Reed had written the song in 1964 while still a songwriter for hire for Pickwick Records, but his employers were understandably wary about allowing him to record it, and it wasn't until the Velvet Underground began performing in late 1965 that the song made its public debut. While "Heroin" hardly endorses drug use, it doesn't clearly condemn it, either, which made it all the more troubling in the eyes of many listeners; at a time when marijuana was still legally classified as a narcotic, the notion of a rock & roll song discussing a dangerous drug without openly condemning it was practically the same thing as a ringing endorsement. Musically, "Heroin" was every bit as challenging as it was thematically; few rock songs of the period made better or more intelligent use of dynamics, and the slow build through the verses into the manic frenzy of the song's conclusion sounded like nothing else in rock music at the time. In addition, John Cale's screeching, atonal viola helped introduce the use of serious dissonance to pop music; along with Roger McGuinn's guitar breaks in "Eight Miles High," it was one of the first examples of the lessons of free jazz or the avant-garde finding a willing student in rock music. While Lou Reed's solo recording of the song on the live album Rock n Roll Animal smoothed out a few of the rough edges, even in its meekest recorded version the song remained a dark and troubling masterpiece. - Mark Deming

There She Goes Again

Composed By Lou Reed

AMG REVIEW: "There She Goes Again" is the quintessential lo-fi, jangle rock song. Driven by Lou Reed's guitar, Sterling Morrison's bass, and, in this case, the tiny percussion of Mo Tucker, the song is a showcase for Reed's vocal stylings but with a great riff and light pop refrain ("there she goes") at its core. Because the band is better known for its sonic and experimental work, "There She Goes Again" is a bit of an anomaly (though they made a handful of jangle-poppers like "Beginning to See the Light") in their rich and varied catalog. The less said about the lyric, the better. It's less than woman-friendly nature made it all the more surprising that R.E.M. recorded a straight version of the song as a B-side to the 1983 reissue of the single "Radio Free Europe" (it also appears on the CD Dead Letter Office). The song was one of the band's early live concert staples; because they also recorded the Velvets' "Pale Blue Eyes," the band is often cited as spearheading the unofficial Velvet Underground revival sparked in the '80s which resulted in the reissue of all of the band's long out-of-print recordings. - Denise Sullivan

The Velvet Underground

Formed 1964 in New York, NY

Disbanded 1973

Group Members John Cale Nico Lou Reed Maureen Tucker Willie "Loco" Alexander Sterling Morrison Doug Yule

Few rock groups can claim to have broken so much new territory, and maintain such consistent brilliance on record, as the Velvet Underground during their brief lifespan. It was the group's lot to be ahead of, or at least out of step with, their time. The mid- to late '60s was an era of explosive growth and experimentation in rock, but the Velvets' innovations - which blended the energy of rock with the sonic adventurism of the avant-garde, and introduced a new degree of social realism and sexual kinkiness into rock lyrics - were too abrasive for the mainstream to handle. During their time, the group experienced little commercial success; though they were hugely appreciated by a cult audience and some critics, the larger public treated them with indifference or, occasionally, scorn. The Velvets' music was too important to languish in obscurity, though; their cult only grew larger and larger in the years following their demise, and continued to mushroom through the years. By the 1980s, they were acknowledged not just as one of the most important rock bands of the '60s, but one of the best of all time, and one whose immense significance cannot be measured by their relatively modest sales.

Historians often hail the group for their incalculable influence upon the punk and new wave of subsequent years, and while the Velvets were undoubtedly a key touchstone of the movements, to focus upon these elements of their vision is to only get part of the story. The group was uncompromising in their music and lyrics, to be sure, sometimes espousing a bleakness and primitivism that would inspire alienated singers and songwriters of future generations. But their colorful and oft-grim soundscapes were firmly grounded in strong, well-constructed songs that could be as humanistic and compassionate as they were outrageous and confrontational. The member most responsible for these qualities was guitarist, singer, and songwriter Lou Reed, whose sing-speak vocals and gripping narratives have come to define street-savvy rock & roll.

Reed loved rock & roll from an early age, and even recorded a doo-wop type single as a Long Island teenager in the late '50s (as a member of the Shades). By the early '60s, he was also getting into avant-garde jazz and serious poetry, coming under the influence of author Delmore Schwartz while studying at Syracuse University. After graduation, he set his sights considerably lower, churning out tunes for exploitation rock albums as a staff songwriter for Pickwick Records in New York City. Reed did learn some useful things about production at Pickwick, and it was while working there that he met John Cale, a classically-trained Welshman who had moved to America to study and perform "serious" music. Cale, who had performed with John Cage and LaMonte Young, found himself increasingly attracted to rock & roll; Reed, for his part, was interested in the avant-garde as well as pop. Reed and Cale were both interested in fusing the avant-garde with rock & roll, and had found the ideal partners for making the vision (a very radical one for the mid-'60s) work; their synergy would be the crucial axis of the Velvet Underground's early work.

Reed and Cale (who would play bass, viola, and organ) would need to assemble a full band, making tentative steps along this direction by performing together in the Primitives (which also included experimental filmmaker Tony Conrad and avant-garde sculptor Walter DeMaria) to promote a bizarre Reed-penned Pickwick single ("The Ostrich"). By 1965, the group was a quartet called the Velvet Underground, including Reed, Cale, guitarist Sterling Morrison (an old friend of Reed's), and drummer Angus MacLise. MacLise quit before the band's first paying gig, claiming that accepting money for art was a sellout; the Velvets quickly recruited drummer Maureen Tucker, a sister of one of Morrison's friends.

Even at this point, the Velvets were well on their way to developing something quite different. Their original material, principally penned and sung by Reed, dealt with the hard urban realities of Manhattan, describing drug use, sadomasochism, and decadence in cool, unapologetic detail in "Heroin," "I'm Waiting for the Man," "Venus in Furs," and "All Tomorrow's Parties." These were wedded to basic, hard-nosed rock riffs, toughened by Tucker's metronome beats; the oddly tuned, rumbling guitars; and Cale's occasional viola scrapes. It was an uncommercial blend to say the least, but the Velvets got an unexpected benefactor when artist and all-around pop-art icon Andy Warhol caught the band at a club around the end of 1965. Warhol quickly assumed management of the group, incorporating them into his mixed-media/performance art ensemble, the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. By spring 1966, Warhol was producing their debut album.

Warhol was also responsible for embellishing the quartet with Nico, a mysterious European model/chanteuse with a deep voice whom the band accepted rather reluctantly, viewing her spectral presence as rather ornamental. Reed remained the principal lead vocalist, but Nico did sing three of the best songs on the group's debut, often known as "the banana album" because of its distinctive Warhol-designed cover. Recognized today as one of the core classic albums of rock, it featured an extraordinarily strong set of songs, highlighted by "Heroin," "All Tomorrow's Parties," "Venus in Furs," "I'll Be Your Mirror," "Femme Fatale," "Black Angel's Death Song," and "Sunday Morning." The sensational drug-and-sex items (especially "Heroin") got most of the ink, but the more conventional numbers showed Reed to be a songwriter capable of considerable melodicism, sensitivity, and almost naked introspection.

The album's release was not without complications, though. First, it wasn't issued until nearly a year after it was finished, due to record-company politics and other factors. The group's association with Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable had already assured them of a high (if notorious media) profile, but the music was simply too daring to fit onto commercial radio; "underground" rock radio was barely getting started at this point, and in any case may well have overlooked the record at a time when psychedelic music was approaching its peak. The album only reached number 171 in the charts, and that's as high as any of their LPs would get upon original release. Those who heard it, however, were often mightily impressed; Brian Eno once said that even though hardly anyone bought the Velvets records at the time they appeared, almost everyone who did formed their own bands.

A cult reputation wasn't enough to guarantee a stable livelihood for a band in the '60s, and by 1967 the Velvets were fighting problems within their own ranks. Nico, never considered an essential member by the rest of the band, left or was fired sometime during the year, going on to a fascinating career of her own. The association with Warhol weakened, as the artist was unable to devote as much attention to the band as he had the previous year. Embittered by the lukewarm reception of their album in their native New York, the Velvets concentrated on touring cities throughout the rest of the country. Amidst this tense atmosphere, the second album, White Light/White Heat, was recorded in late 1967.

Each of the albums the group released while Reed led the band was an unexpected departure from all of their other LPs. White Light/White Heat was probably the most radical, focusing almost exclusively on their noisiest arrangements, over-amped guitars, and most willfully abrasive songs. The 17-minute "Sister Ray" was their most extreme (and successful) effort in this vein. Unsurprisingly, the album failed to catch on commercially, topping out at number 199.

By the summer of 1968, the band had a much graver problem on its hands than commercial success (or the lack of it). A rift developed between Reed and Cale, the most creative forces in the band and, as one could expect, two temperamental egos. Reed presented the rest of the band with an ultimatum, declaring that he would leave the group unless Cale was sacked. Morrison and Tucker reluctantly sided with Lou, and Doug Yule was recruited to take Cale's place.

The group's self-titled third album (1969) was an even more radical left turn than White Light/White Heat. The volume and violence had nearly vanished; the record featured far more conventional rock arrangements that were sometimes so restrained it seems as though they were making an almost deliberate attempt to avoid waking the neighbors. Yet the sound was nonetheless effective for that; the record contains some of Reed's most personal and striking compositions, numbers like "Pale Blue Eyes" and "Candy Says" ranking among his most romantic, although cuts like "What Goes On" proved they could still rock out convincingly (though in a less experimental fashion than they had with Cale). The approach may have confused listeners and critics, but by this time their label (MGM/Verve) was putting little promotional resources behind the band anyway.

Even in the absence of Cale, the Velvets were still capable of generating compelling heat on-stage, as 1969: Velvet Underground Live (not released until the mid-'70s) confirms. MGM was by now in the midst of an infamous "purge" of its supposedly drug-related rock acts, and the Velvets were setting their sights elsewhere. Nevertheless, they recorded about an album's worth of additional material for the label after the third LP, although it remains unclear whether this was intended for a fourth album or not. Many of the songs, though, were excellent, serving as a bridge between The Velvet Underground and 1970's Loaded; a lot of it was officially released in the 1980s and 1990s.

The beginning of the 1970s seemed to herald considerable promise for the group, as they signed to Atlantic, but at this point the personnel problems that had always dogged them finally became overwhelming. Tucker had to sit out Loaded due to pregnancy, replaced by Yule's brother Billy. Doug Yule, according to some accounts, began angling for more power in the band. Unexpectedly, after a lengthy residency at New York's famous Max's Kansas City club, Reed quit the band near the end of the summer of 1970, moving back to his parents' Long Island home for several months before beginning his solo career, just before the release of Loaded, his final studio album with the Velvets.

Loaded was by far the group's most conventional rock album, and the most accessible one for mainstream listeners. "Rock and Roll" and "Sweet Jane" in particular were two of Reed's most anthemic, jubilant tunes, and ones that became rock standards in the '70s. But the group's power was somewhat diluted by the absence of Tucker, and by the decision to have Doug Yule handle some of the lead vocals. Due to Reed's departure, though, the group couldn't capitalize on any momentum it might have generated. Unwisely, the band decided to continue, though Morrison and Tucker left shortly afterward. That left Doug Yule at the helm of an act that was the Velvet Underground in name only, and the 1973 album that was billed to the group (Squeeze) is best forgotten, and not considered as a true Velvets release.

With Reed, Cale, and Nico establishing important solo careers of their own, and such important figures as David Bowie, Brian Eno, and Patti Smith making no bones about their debts to the band, the Velvet Underground simply became more and more popular as the years passed. In the 1980s, the original albums were reissued, along with a couple of important collections of outtakes. Hoping to rewrite the rules one last time, Reed, Cale, Morrison, and Tucker attempted to defy the odds against successful rock reunions by re-forming in the early '90s (Nico had died in 1988). A European tour, and a live album, was completed in 1993 to mixed reviews; before a planned American jaunt could start, Reed and Cale (who have feuded constantly over the past few decades) fell out yet again, bringing the reunion to a sad close. Sterling Morrison's death from illness in 1995 seems to have permanently iced any prospect of more projects under the Velvet Underground name, although a few of the surviving members played together when they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. By that time, an impressive five-CD box set (containing all four of the studio albums issued when Reed was in the band, as well as a lot of other material) was available to enshrine the group's legacy for the ages. - Richie Unterberger

1967 The Velvet Underground & Nico Verve

1967 White Light/White Heat Verve

1969 The Velvet Underground Verve

1970 Loaded Warner

1972 Live at Max's Kansas City Atlantic

1973 Squeeze Polydor

1974 1969: Velvet Underground Live Mercury

1974 1969: Velvet Underground Live, Vol. 1 Mercury

1974 1969: Velvet Underground Live, Vol. 2 Mercury

1974 Live with Lou Reed Mercury

1976 Live Mercury

1993 Live MCMXCIII [Single Disc] Warner

1993 Live MCMXCIII [Double Disc] Warner