|

|

|

01 |

All Your Love |

|

|

|

04:46 |

|

|

02 |

Snowy Day |

|

|

|

03:46 |

|

|

03 |

Sitting On Top Of The World |

|

|

|

03:37 |

|

|

04 |

That Collins Thing |

|

|

|

04:41 |

|

|

05 |

'Sixty-Six |

|

|

|

04:53 |

|

|

06 |

Diving Duck |

|

|

|

02:56 |

|

|

07 |

Mystery Train |

|

|

|

04:35 |

|

|

08 |

Close To Me |

|

|

|

04:55 |

|

|

09 |

Killing Floor |

|

|

|

02:34 |

|

|

10 |

Dust My Broom |

|

|

|

03:22 |

|

|

11 |

Blu-E |

|

|

|

05:12 |

|

|

12 |

Sidetracked |

|

|

|

05:02 |

|

|

|

| Studio |

World Studio |

| Country |

USA |

| Cat. Number |

HMS-215 |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

Elliott Sharp - E# electric guitar, lap steel guitar

David Hofstra - electric bass, acoustic bass

Joseph Trump - drums

Produced by Ellitott Sharp

Date of Release Aug 5, 1994

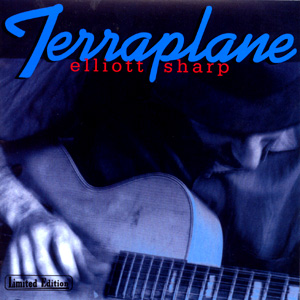

AMG EXPERT REVIEW: Elliott Sharp's musical excursions take him into some of the most extreme and avant-garde territory of his contemporaries, so much so that it's hard to be surprised when he swings around to traditionalism again; Terraplane is a straight-out blues record (yes, blues), with Sharp applying his conventional guitar skills to uptempo, rollicking and utterly normal blues shuffles. It's hard to imagine that those who have enjoyed Sharp's experimental work with Carbon will be particularly taken with Terraplane, except for as a novelty — but there's undoubtedly a small group of Sharp's devotees who will enjoy it immensely. — Nitsuh Abebe

Who would have guessed that Elliott Sharp, that avant-garde, mad scientist, guitarist supreme, would play such soulful blues? On Terraplane, Sharp takes on 12 tracks either written or popularized by his blues idols, as well as four original compositions in similar styles. Ably accompanied by bassist David Hofstra and drummer Joseph Trump, he is nothing less than absolutely convincing here. Dispensing with the irony and impotent intellectualism that often hampers his other work, Sharp plays his guitar with verve and spirit. He showcases a good variety of tones and approaches to the instrument as well, showing that, without a doubt, he has done his homework. In addition to his conventional guitar playing, he also plays some mean lap steel, as capably demonstrated on "Sitting on Top of the World." Every once in a while, Sharp's avant-garde roots come to the forefront, but when they do, they remind the listener more of Jimi Hendrix' extremely progressive approach to the blues than anything else. The original compositions are quite good, with such memorable moments as the funky vamp of "'Sixty-Six" or the unusual turnaround of "Snowy Day." Sharp has never sounded this spontaneous and as in-control of his instrument. Fans of blues and blues guitar should do themselves a favor and pick this up, as they will no doubt be pleasantly surprised. Dirty, funky, and full of the genuine spirit of the blues, Terraplane, although an anomaly with regard to sound and approach, is one of the high points of Sharp's extensive catalog. - Daniel Gioffre

1. All Your Love (Rush) - 4:46

2. Snowy Day (Sharp) - 3:46

3. Sitting on to of the World (Traditional) - 3:37

4. That Collins Thing (Sharp) - 4:41

5. Sixty-Six (Sharp) - 4:53

6. Diving Duck (Estes) - 2:56

7. Mystery Train (Crudup) - 4:35

8. Close to Me (Williamson) - 4:55

9. Killing Floor (Burnett/Howlin' Wolf) - 2:34

10. Dust My Broom (James) - 3:22

11. Blu-E (Sharp) - 5:12

12. Side Tracked (King) - 5:02

Elliott Sharp

Born Mar 1, 1951 in Cleveland, OH

Elliott Sharp began playing the piano at six. According to Sharp, he was performing concerts by age eight. Sharp claims that his parents wanted him to be both a concert pianist and a scientist. He gave up piano, first in favor of the clarinet and then the guitar. His interest in science led him to build his own effects boxes for the instrument. He became intrigued with all types of experimental music, from contemporary classical to free jazz and sophisticated rock. Sharp studied anthropology at Cornell, where he played in a band and took an electronics class with synthesizer inventor Robert Moog. At Bard College he studied with free jazz pioneer Roswell Rudd (future Lounge Lizards John and Evan Lurie were classmates). He went to graduate school in Buffalo, where his academic advisor was Morton Feldman. He moved permanently to New York City in 1979, where he played gigs at various underground performance spaces, including the notorious Mudd Club. In the '80s Sharp became a major figure on the downtown New York experimental music scene, collaborating with many of it's most prominent players, including John Zorn, Wayne Horvitz, Bobby Previte, and Butch Morris. Over the years, Sharp has led his own bands more often than not. His music draws upon the wide range of his influences, from Coltrane to Zappa to Xennakis and beyond. An improviser at heart, Sharp's compositions tend to be quite loose, allowing plenty of room for the musicians to roam. Among his recent projects is the blues/hardcore/free jazz hybrid Terraplane, with bassist Dave Hofstra, saxophonist Sam Furnace, and drummer Sim. - Chris Kelsey

1977 Hara Zoar

1979 Resonance Zoar

1980 Rhythms and Blues Zoar

1981 I/S/M Zoar

1982 I/S/M:R Zoar

1982 Nots Atonal

1983 (T)here Zoar

1984 Carbon Atonal

1985 Marco Polo's Argali/Carbon: Six Songs Dossier

1985 Spring & Neap: Live at Music Merge Festival,... Zoar

1986 Fractal Dossier

1986 The Virtual Stance Dossier

1987 In the Land of the Yahoos SST

1987 Tessalation Row SST

1988 Larynx SST

1989 Hammer, Anvil, Stirrup SST

1990 K!L!A!V! Newport

1990 Datacide Enemy

1991 Tocsin Enemy

1992 Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Yahoos Sulphur

1993 Truthtable Homestead

1993 Yunta and Jiraba Akabana

1993 Amusia Atavistic

1994 Terraplane Homestead

1994 Cryptid Fragments Extreme

1994 ' Dyners Club Intakt

1995 Tectonics Knitting

1995 Interference Atavistic

1995 Psycho-Acoustic Victo

1996 Sferics Atonal

1996 Blackburst Psycho-Acoustic Victo

1996 XenocodeX Tzadik

1997 Figure Ground Tzadik

1998 Field & Stream Knitting

1998 Rwong Territory [live] Cavity Search

2000 Blues for Next Knitting

2001 Suspension of Disbelief Tzadik

2002 Anostalgia Grob

2002 The Prisoner's Dilemma Grob

2002 Beyond Auditorium

Beneath the Valley of the Ultra Vixens Sulphur

Twistmap Ear-Rational

Bootstrappers Gi=Go Atonal

ELLIOTT SHARP AND DAVID FULTON

Hara (Zoar) 1977

ELLIOTT SHARP

Resonance (Zoar) 1979

Rhythms and Blues (Zoar) 1980

ISM (Zoar) 1982

I/S/M:R (Zoar) 1982

Nots (UK Glass) 1982 (Ger. Atonal) 1992

(T)here (Zoar) 1983

Live in Tokyo [tape] (Zoar) 1985

Virtual Stance (Ger. Dossier) 1986

In the Land of the Yahoos (SST) 1987

K!L!A!V! (Newport Classic) 1990

Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Yahoos (Sulphur/Silent) 1992

Westwerk (Ger. Ear-Rational) 1993

Terraplane (Homestead) 1994

'Dvners Club (Sw. Intakt) 1994

Arc 1: I/S/M 1980-1983 (Atavistic) 1996

Figure Ground (Tzadik) 1997

Arc 2: The Seventies (1972-79) (Atavistic) 1997

Arc 3: Cyberpunk and the Virtual Stance (Atavistic) 1998

Suspension of Disbelief (Tzadik) 2001

ELLIOTT SHARP/CARBON

Datacide (Enemy) 1889

Carbon (Atonal) 1984

Marco Polo's Argali/Carbon: Six Songs (Ger. Dossier) 1985

Fractal (Ger. Dossier) 1986

Larynx (SST) 1988

Monster Curve (SST) 1989

Sili/Contemp/Tation (Ear-Rational) 1990

Tocsin (Enemy) 1992

Truthtable (Homestead) 1993

Autoboot (no label) 1993

Amusia (Atavistic) 1994

Interference (Atavistic) 1995

ELLIOTT SHARP/ORCHESTRA CARBON

Abstract Repressionism: 1990-99 (Can. Les Disques Victo) 1992

ELLIOTT SHARP AND THE SOLDIER STRING QUARTET

Tessalation Row (SST) 1987

Hammer, Anvil, Stirrup (SST) 1989

Twistman (Ger. Ear-Rational) 1991

Cryptid Fragments (Extreme) 1993

ELLIOTT SHARP: TECTONICS

Tectonics (Ger. Atonal) 1995

Field & Stream (Knitting Factory Works) 1998

Errata (Knitting Factory Works) 1999

ELLIOTT SHARP'S TERRAPLANE

Blues for Next (Knitting Factory Works) 2000

SEMANTICS

Semantics (Rift) 1985

Bone of Contention (SST) 1987

BOOTSTRAPPERS

Bootstrappers (New Alliance) 1990

Garbage In=Garbage Out (Ger. Atonal) 1992

BACHIR ATTAR AND ELLIOTT SHARP

In New York (Enemy) 1990

BOODLERS

Boodlers (Cavity Search) 1994

ELLIOTT SHARP/ZEENA PARKINS

Psycho Acoustic (Can. Les Disques Victo) 1995

HOOSGOW

Mighty (Homestead) 1996

There aren't many musicians who need so many different band names under which to work. But Elliott Sharp has that many different ideas, sounds and styles swirling in his clean-shaven head. And, at the expense of a linear career that could earn him bigger bucks or notoriety, he has explored them all. Sharp is a composer, improviser, instrument inventor and mathematician able to play clarinet, saxophone, guitar, bass, sampler, piano, computer and instruments of his own creation - like the slab, pantar and violinoid. Since 1979, he has been based in Manhattan, making a name for himself as a freelance avant-gardist willing to collaborate with anyone, from Pere Ubu to the Kronos Quartet, and try anything, from jungle dance music to the blues to compositions based on fractals and the Fibonacci number series.

Since the start of the '90s, Sharp has put an end to a dozen side projects and started a dozen more, increasing, along the way, the political content of his music and his kinship to experimental dance music. Where Carbon was a vehicle for some of Sharp's noisiest, densest, longest experiments in the '80s, it began transforming into a sort of industrial metal band on Datacide and solidified, for the first time ever, its lineup (as a quintet) on Tocsin. (The Orchestra Carbon album Abstract Repressionism: 1990-99, a seven-movement, hour-long composition, offers a glimpse into the band's past.)

On the angrier Truthtable and Amusia albums, Sharp's distorted voice howls about conspiracy theories and corruption as Zeena Parkins plays her electric harp like a lead guitar and Sharp, bassist Marc Sloan and sampler-player David Weinstein grind out sheets of rhythmic, metallic noise. On Interference and parts of Autoboot (an authorized bootleg Sharp made mixing unreleased Carbon studio tracks and excerpts from live performances), Carbon focuses less on Sharp's paranoia in favor of more abstract instrumentals endowed, on some tracks, with the more atmospheric minimalism of ambient music.

One of Sharp's most accessible solo records of late is Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Yahoos (a Russ Meyer-titled sequel to 1987's In the Land of the Yahoos). Each of the fragmented pop songs lasting two to three minutes enlists a different avant-garde musician, from Eugene Chadbourne playing piano and singing the blues on "Return of the Pharm Boys" to Sussan Deihim wailing ethereal Middle Eastern vocals on "X-Plicit."

If it wasn't for the distinctly chunky sound and warbling slides of Sharp's guitar, Terraplane would sound as if another musician made it. With David Hofstra on bass and Joseph Trump on drums, Sharp reinvents himself as the thinking-person's bluesman. The album opens with Otis Rush's "All Your Love" and continues by mixing Sharp's own, convincing 12-bar compositions with Elmore James and Freddie King standards. On 'Dyners Club, the composer moves forward half a century, performing with his guitar quartet. The band retunes its instruments to riff out-of-phase on "Residue" and explore Sonic Youth's cacophonous terrain on "Flowtest."

Other than Nots, a reissue of a 1982 album augmented by unreleased and rare material he recorded in the early '80s, Sharp's solo albums this decade aim to convert mathematical and scientific terms and theories into music. One of the best of these is Tectonics, a sophisticated record in which machine-driven techno rhythms and free jazz merge in an exploration of the deformities of the earth's surface (which range from songs about geology to one about Newt Gingrich).

Cryptid Fragments uses the scientific term for a creature whose existence has been documented only anecdotally (like Bigfoot) as an analogy for the instruments in its title track. Sharp created the seventeen-minute "Cryptid Fragments" by giving cellist Margaret Parkins and violinist Sara Parkins a score to play. He then spent 150 hours at the computer rearranging and processing the music until what was left was not the sound of the violin and the cello but those of virtual instruments that exist only in computer memory. "Shapeshifters," also on the album, uses a similar process to manipulate the scraping and sliding of the Soldier String Quartet.

Sharp's avant-garde jam bands have yet to approximate the chaotic beauty of his '80s group the Semantics. The Boodlers, a trio with Fred Chalenor on bass and Henry Franzoni on percussion, offers competent but uninteresting laid-back, slightly psychedelic avant-jazz and computer-processed noise. In its second incarnation, Bootstrappers - Sharp supplemented by bass (Thom Kotik) and percussion (Jan Kotik) - veers away from jazz and all-out noise in favor of industrial-sounding avant-garde funk. (The rhythm section on Bootstrappers is Mike Watt and George Hurley of fIREHOSE.)

Sharp's collaborations don't always work. In New York, an improvisation with Bachir Attar, the leader of Morocco's Master Musicians of Joujouka, is a case in point. On the album's best tracks, Attar's flutes and strings spin and soar over Sharp's electric guitar underpinning. But the intrusion of a crudely programmed drum machine and a disequilibrium between Attar's spiritual, buoyant playing and Sharp's craggy, scientific jamming make it an experiment that doesn't quite succeed. Still, like everything Sharp has done, this imaginative undertaking is better heard than ignored.

[Neil Strauss]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Elliott Sharp Interview

Prolific, huh? You want prolific do you? OK then, I have an Elliott Sharp discography sitting here next to me with over 136 entries. Is that prolific enough? So he's hardly Sun Ra ... I know, I know. Of course, there's more to Elliott Sharp than just his astonishing work rate, but if the quantity of his music doesn't impress you, the quality and diversity will.

Even by downtown New York's excessively eclectic standards, Sharp is something of a phenomenon. Barely has he returned from a tour of Europe with his avant-rock group Carbon (their new album Amusia has just been released by Atavistic and Spectrum / Play It Again Sam) than he has to set everything else aside in order to write a composition for orchestra to a very tight deadline (Racing Hearts, written for the Bang On A Can festival's Spit Orchestra, was premiered in January). Since one rock group is clearly barely enough to keep the man busy, you could instead look out for his electric guitar quartet, Dyner's Club (album recently out from the Swiss Intakt label, they're already performing a new 50-minute composition), or Tektonics, where he controls a drum machine and other electronics via a Buchla Thunder, helped out by Melvin Gibbs on bass, KJ Grant and Dorit Chrysler's vocals. The most recent CD to arrive at ESTHQ was by the Boodlers, an improvisational trio with bassist Fred Chalenor and drummer Henry Franzoni. Straight improv is clearly too much like lazing around for Elliott, as this recording has been heavily sliced-and-diced via digital computer processing. It mostly comes over as more conventional in tone than much of Sharp's music, ditching angular tonalities in favour of rockist guitar solos and lyrical jazz tenor sax, but the digital confusion takes control on the collage-based Cambionics.

There are some people who would suggest that Sharp's rampant eclecticism falls prey to the "jack-of-all-trades" syndrome, and it's a suggestion that contains a grain of truth. But what's interesting about his output is that whether you're listening to a super-dense black-hole of a string quartet, to wired and wily solo blues guitar covers, or to one of his many bitstream juggernaut "rock" groups, there are ideas and attitudes that appear consistently.

Sharp's music embodies the revolution that science has undergone throughout the twentieth century. The age when Newton could formulate simple, precise rules with which to measure and explain the universe has long passed away, via a series of developments that have increasingly revealed the uncertainty principle at the heart of science: quantum uncertainty, chaos maths, fractals, strange attractors. All Sharp's music inhabits this meme-scape, reflecting the paradoxical combination of chaos and order that underlies the new physics. OK, I know, we wouldn't want to get carried away here, after all, it's just music, but however much your humble writer might back up Sharp's achievements with overblown verbiage, it's still true that the relationship between the rational and the irrational is what gives his music its on-edge, wired quality, and what makes it stand out.

I suspect that Elliott himself might be a little more modest, but he's clearly aware of the way in which his music acts as metaphor and representation for more than just a series of notes on a piece of paper. "Music is applied physics - at the risk of spouting 'new age sew-age' it is truly a direct application of vibrating energy systems. When I began to read as a child, I was sucked deeply into the world of sci-fi with Philip K. Dick being a major philosophical influence. A major lesson of both sci-fi and of recent science is that the borderline between them is rather tenuous. The paradigms of reality are continuously being shifted. Music is an abstract language that allows the composer and listener to continuously re-define reality - to process them, to post new definitions - a feedback loop."

If it's not too much of a jump, perhaps I'd better be a little more down-to-earth. Elliott's musical life began age six, taking piano lessons which led to taking part in a recital at the age of seven. "The 'practice' of piano took its toll on me", Elliott notes, "I hated it and developed asthma which nearly killed me. I long associated the collapse of my lung with piano lessons. I enjoyed the sound of the clarinet and began to study it at eight when offered it as part of school. It provided some sonic satisfaction and seemed physically therapeutic (although once again the so-called 'teaching of music' by bitter and incompetent idiots bothered me intensely)".

As a child, Elliott admits to having been an "extreme science nerd", and with track titles like Gigabytes, Calibrate, and Diffractal it's obvious his interest in science hasn't disappeared. He received a grant from the National Science Foundation to spend a summer at Carnegie-Mellon University.

"Rock in the form of the Beatles, Stones, Yardbirds, surf music, Byrds woke me up. I had discovered Jimi Hendrix and the many forms of the blues and bought a cheap electric guitar. I spent my time in the CMU lab designing and building fuzzboxes and playing with a seven-head tape machine. I scammed a midnight to 4am slot on the campus radio station. I would dig through the fairly extensive library and find all kinds of interesting records: the ESP jazz series (Albert Ayler is a fave), Xenakis, Harry Partch, Cage, Stockhausen, Indian music, Tibetan music, gamelan, B'ambuti pygmies, Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, Ornette, Tod Dockstadter, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Lightnin' Hopkins, Pierre Henry, Kagel, Ligeti etc. I immersed myself in sounds and in text about sound (Helmholtz, Cage, Partch, Leroi Jones, Xenakis all wrote important books about music, sound, acoustics; another important one was J.R. Pierce's Symbols, Signals, and Noise). My guitar experiments were informed heavily by all this stuff and the blues also. Blues guitar hit me extremely hard: the guitar was transformed through bending, use of slide, and distortion into a vocal instrument, transcending 'notes', melodies, chords, harmony.

"I played clarinet with a cheap microphone taped to the bell and plugged into a small amp of my own construction. I could do a pretty good imitation of Jeff Beck's ruder guitar solos. When I returned to finish my last year of high school (1968-69) I was more interested in psychedelic guitar noise in all its glory (feedback, preparations, 'extended techniques') than just about anything else (except for blues which I still listen to and play in Terraplane, which now features the vocalist Queen Esther) and I would play in as many situations as I could. I didn't think of what I did as 'Improvisation' or 'Composition'. This awareness came later as I entered into studies and battles in university with Roswell Rudd, physicist Burton Brody, ethnomusicologist Charles Keil, and composers Morton Feldman and Lejaren Hiller."

After a spell at Cornell University, where he performed in psychedelic bands such as St Elmo's Fire and Colonel Bleep, Elliott studied physics, composition, improvisation and ethnomusicology. He moved to the University of Buffalo to continue his studies. His studies with Roswell Budd, the composer and free jazz trombonist sparked an interest in ethnic music, which he developed at Buffalo with Charles Kell (he played guitar and saxophone in Kell's Outer Circle Orchestra). But if these learning experiences would have an obvious effect on his music, I was puzzled to discover precisely how well he'd got on with composer Morton Feldman, one of the teachers at Buffalo's Center for Creative and Performing Arts at the time. After all, the crazed abandon of psychedlic rockers like the Grateful Dead or Jimi Hendrix can still be heard in much of Elliott's music ю check out the guitar solos on Carbon's Tocsin for one of many examples. The blues have been an ongoing if often submerged influence - 1994's Terraplane album mixes Sharp originals with covers of songs by Otis Rush, Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson and others. And it's difficult to find a Sharp album that doesn't bear the influence of ethnic time-signatures, harmonies, timbre or rhythm. Morton Feldman's music, which often relies on extremely slow playing, allowing (say) piano notes to linger beautifully, seems a pole apart.

"My encounters with Feldman remain perversely inspirational. I liked much of Feldman's music and enjoyed texts of his that I had come upon. At the University of Buffalo, he was the philosophical emperor of the music department. I took part in the Composer's Forum which held discussions (or rather Feldman held court and we listened) and presented our music. My first concert used a 90-second through-composed soprano sax melody played through a ring-modulator to tape, slowed down to half-speed, with a now 180-second melody, ring-modulated, over-dubbed. This tape was played back at half-speed again yielding a 360-second background over which I improvised again on soprano. Feldman called me into his office the next morning. In his thick Brooklyn accent with 2 inches of cigarette ash ready to anoint me, he pronounced 'Improvisation, I don't buy it!' and dismissed me.

"At our next Composers Forum event in March 1975 I presented my Attica Brothers piece based upon the eponymous prison uprising (I was involved in some support groups and activities around this). The piece used a microtonal melody (for maximum buzz and difference tones) for electrified string quartet plus conga drums, rock drums (the beginning of my association with Bobby Previte) and orchestral percussion. The parts (written out) were conducted by time-cards. The conga player played a 16th note pulse throughout. As we were about to commence the piece in a packed concert-hall, Feldman stood up and said 'Where's his music-stand?' pointing to the conga drummer. I replied that he didn't need one as he was cued by the conductor to begin and end. Feldman got up on stage, grabbed a music-stand and placed it in front of the conga drummer saying 'Now you can play it.' Again I was called into his office the next morning and told: 'You put too much sociology in your music - music should be listened to sitting in red plush seats and your music is for sitting on the floor!'"

As I said, Elliott's music is littered with pirated ethnic elements. From his early music I'd recommend the jazz-rock (now there's a fine example of how pigeonholing never works) Monster Curve CD collection. If the liner notes didn't tell you, you'd never guess that abstruse maths (the Fibonacci series) was used to generate tunings and structure, because it's the muscular, fevered, euphoric quality of the music that hits first. The up-front saxophones remind me of Moroccan ritual music, and the interlocking polyrhythms, overtone singing and tamboura-like strings (on Not-Yet-Time). This is hardly Paul Simon-style ethno-politeness, though, it's passionate music which re-creates the energetic rawness of the original inspirations rather than just the superficial trappings. The tracks originally from the Fractal album exemplify the musical paradoxes at work, combining these "ethnic qualities" with musical structures based on fractal geometry, although to my mind the turbulence thankly overpowers any hint of the ummm, algorithmic contents.

Similar ideas appear in a more extended form on the three-quarter-hour Larynx, a composition for four brass players, four drummers, string quartet and Sharp himself (playing sax, clarinet, sampler, electric guitar and bass). The brass players also play some of Sharp's invented instruments, including the pantar (a four-stringed, contact-miked large metal pan played like a guitar) and the slab (solid blocks strung as horizontal basses and bowed or struck like a dulcimer). The music owes a lot to the overtone-singing of the Mongolian tuvan, the Inuit or Tibetan Buddhist monks, with all the instruments tuned to accentuate the harmonic series. It's formidable, fertile music.

"As one throat-singer is an entire orchestra, I wanted an orchestra to function as my own throat. The source material was inspiration and metaphor. This piece was the culmination of my work with Fibonacci numbers, fractal geometry, and chaos theory. The Fibonacci numbers were used to generate structures, tunings (in just intonation), and rhythms. Macro- and micro-structures echo each other and appear in various forms throughout the piece - sonic ideas may appear in the strings in one place, in the percussion in another, in the homemades (slabs, pantars) in yet another place - always transformed, shifted in proportion or shape. Elements of improvisation would appear sometimes as foreground, sometime as background - even these roles could shift.

"The rich and varied functionality of music in non-western cultures has always been an important attraction for me (aside from the obvious: pungent and extreme timbres, complex rhythms, microtonality, incredible melodies). Music in western life becomes more de-valued everyday: a soundtrack for consumption. The extensive use of appropriation is as much the symptom as the culprit. In the 70s and 80s artists used appropriation to comment upon society and culture. Now it is used to disguise a general lack of originality and creativity. Icons are plucked from the datastream and recombined endlessly. Novelty effects are created - for me the affect is trivial. Witness the way samplers are put to use 99% of the time. A sure sign of a stagnant culture when the watchword is retro and people march full-speed backwards with a smug and 'ironic' smirk. Smaller and smaller chunks are re-cycled - now artists try to capitalize on nostalgia not for past decades but for past weeks or days. As we are surrounded by increasing amounts of raw data, we need some transformative mechanism to filter it and render it 'useful'."

The processing of data is a frequent theme in Elliott's music. To quote theorist Arthur Kroker,

"It entertains opposite impulses simultaneously. It's got the crusading spirit for the technical apocalypse. At the same time, it revels in a kind of violent primitivism ... It's perfectly schizophrenic".

He may have been talking about modern American culture, but it could just as well apply to Elliott Sharp's music.

"I see music as an agent of psycho-acoustic chemical change. Intent as a composer is of vital importance! I had always found it better to learn a technique or approach and then bend it to one's own talents or limitations. My own practice of khoomei singing is clearly related to its Tuvan sources but no one would mistake it for Tuvan. When I use this singing or some other 'extended technique' in a composition/performance, I'm providing a sound that has it's own resonant power in its inherent nature as well as providing 'markers' to steer the listener to other places and attitudes."

Elliott moved to New York in 1979, realising that it was probably the only place where he could pursue his musical interests, have an audience, and find like-minded people to interact with. "I had had some contact with some people including Giorgio Gomelsy, Eugene Chadbourne, Bill Laswell before I moved there and found it quite easy to make musical connections. I was living in cultural and physical isolation in western Massachusetts. Moving to NY was like 'coming home' - I immediately connected with the improvisors and played in the no-wave scene around Tier 3 and Mudd Club and Hurrah as well as doing session work, odd gigs and playing for dance companies. One day might include five gigs in extremely different environments, starting at noon and finishing with an after-hours gig at 6 in the morning. NY is about diversity - continuously changing scenes and casts of characters. A lot of the best musical experiences are social as much as musical. These factors can't be separated."

He also found time to run his own label, Zoar Records, releasing his own records as well as albums by Robert Previte, Mofungo, Guy Klucevsek and Charles Noyes. Zoar was also responsible for the classic downtown New York compilation State of the Union. Then, of course, there were the bands: Semantics, Bootstrappers, The Sync, Frame, Scanners, GX4, Sonicphonics, Terraplane, Slan, Dyners Club, Boodlers etc where Sharp teams up with Samm Bennett, John Zorn, Mike Watt, David Linton, Anthony Coleman, Geoff Serle, and more other left-field, mostly-NY notables than you can shake a microphone at. Elliott's own band, Carbon, have been the most long-lived and prolific of them all. For the most part, they've purveyed neurotic, angular funk-jazz-rock, at times as inoffensive as the worst of their NY neighbours, at times both looser and more edgy. I'd suggest Monster Curve, Datacide and Tocsin as suitable introductions. Expect relentless polyrhythms; trembling, pointillistic sax; guitars that sound like hammering on electrical cables; pointless tangents and pointed chords.

He has also remained visible in the world of free improvisation (see, for example, EST 6's interview with Nicolas Collins), although none of his recent recordings have been entirely improvised.

"I was never a devout free improvisor - intent and structure (information in process) were always too important. Improv can be fun to do but not always to listen to. I had always had strong feelings about how I wanted music to be manifested: the sonic elements, the structural elements, the balance of order and chaos, use of improvisation. I tried to pull these ideas together in 1980 as 'ir/rational music': ir being a bad pun on the ear and hearing. Rational having to do with structure, order and intent. Overall is the irrational: the tangential and spontaneous. Improvisation brings the music to life. Music should be MUSIC - the thing that can't be defined but that which maps sound to other natural forms and processes. Not all elements are always perceivable. I like it when the music reveals itself in layers and over time and when a given composition can have a very clear identity while manifesting unique internal detail with every performance. The various elements may exist as major guiding forces at one point and then become merely tools of orchestration. I have found these tools to sometimes recede in usefulness and then return again, screaming for attention. Fibonacci numbers are one such element: in my recent orchestra piece for improvisors, Cochlea (commissioned for the Inner Ear festival in Linz, Austria, March 1995) the fibonacci numbers were a predominant factor. As one applies these principles to different groupings of musicians or playing situations, an overall style emerges, no matter what the situation."

Sometimes, Elliott's music structured on some abstruse mathematical algorithm sounds as chaotic as the freely improvised music, and vice versa. It's not unlike serialist composition where however clear the mathematical structure behind the composition may be to the writer, it's rarely if ever audible. Fortunately, with Elliott's music, the structuring principles are just means to an end. If he often uses fibonacci-related tunings (the fibonacci series comprises the numbers 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21 etc), it's because they sound good, as much as anything else.

Elliott has also become increasingly known for his compositions. Larynx stuck to an expanded version of the typical Carbon instrumentation, as did Sili/Contemp/Tation and the unreleased Redrum and Serrate. K!L!A!V! comprises "extreme music for various keyboards", encompassing sampler, commercial keyboards and piano. Sharp's Skew appears on the album First Program in Standard Time by the New York Composers' Orchestra (mostly a brass/woodwind ensemble).

Several albums exist with music for string quartet or similar instruments. Abstract Repressionism (the title is a Bob Black quote, trivia fans) is for the "Orchestra Carbon", and shows that Xenakis and Penderecki weren't the only composers who liked to fashion chaos and energy from the paradoxically taut, nervous quality of stringed instruments. It's a difficult, atonal, fractured piece, but a rewarding one. Hammer Anvil Stirrup, featuring the Soldier String Quartet (and combining the title track with the entirety of the earlier Tessalation Row album), is a more mixed affair, although the swirling, squawking layers of stringy, metallic wires on Tessalation Row; work well against each other, and there are even moments of lovely slow droning amidst the more usual storm of rapid-cut bowing. Cryptid Fragments (which, irritatingly, features some but not all of the Twistmap album) also features the Soldier String Quartet, but is more cartoony in style. On the track Shapeshifters, squeaky string harmonies vie with creaky door movements, tippy-toe plucking and rubber band rabbit hopping, suggesting that John Zorn isn't the only musician to have learnt a trick or two from Carl Stalling.

Interview conducted by eMail, March 1995, by Brian Duguid.

Elliott Sharp

photo credit - jane chafin

Interview by John Kruth (November 2001)

The Hardcore Junior Scientist Reveals the Pure Mystery of Fruit Flies, Noodles and other Large Musical Forces

On my way over to Elliott Sharp's downtown flat, I walked past Tompkins Square Park, the site of the annual Charlie Parker Festival. There was a guy standing out in the pouring rain, squawking on an alto sax. The word 'commitment' suddenly popped into my noggin. Commitment - committing - or being committed, it's a fine line indeed. It's December 13th 1999, Joseph Heller, author of the brilliant novel Catch 22 (ah, I see a theme beginning to take shape here) died today and the world is certainly much poorer and less sane for it. As the century changes many of our best musicians, writers, artists and short-order cooks have gotten their hat and hit the eternal highway. Mr. Sharp, one of the most committed individuals the music world has known in recent years, continues to live true to his vision as an experimental composer, multi-instrumentalist, world-traveling performer and self-described "Zen-Groucho Marxist." He's often calculated, analytical and scientific. Yet Elliott understands the power of free expression, unleashing a flash flood of sound that gushes from his guitar and sax. Sharp roars in a language that reverberates the walls of our ancient caves while sonically spackling the hole in our souls left by such innovative forefathers as Son House and Sun Ra. It's all in a night's work.

I had recently made the aquaintence of the enigmatic Elliott Sharp, although we had been crossing paths for years. it turns out that he's been mesmerized by the Master Musicians of Jajouka as long as i have. Bachir and the brotherhood had brought their village to the city and we found ourselves down at the Knitting Factory for four consecutive infusions of cleansing fire. Along with violinist/guitarist Jonathan Segel who just arrived in town after his tour with Sparklehorse was cancelled after an earthquake in Athens, we joined forces with a tempermental Turkish drummer named Atilla and repaired to Elliott's studio to improvise a set of quirky instrumentals for the Sparkling Beatnik label. Moon Dog Girl by Noodle Shop (our name instantly inspired by a glanc out the window at the corner take out joint's neon sign) was cut live in five hours - start to finish and dedicated to late great Moondog, the famous sightless viking who sang opera outside of carnegie hall for years.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

JK: Today the General Surgeon declared that one out of every five Americans is mentally ill.

ES: And another eighty percent have been already declared incurable! (Laughs) Then there's us, the twenty percent that's not taking Prozac. And what percent of that eighty-percent have guns? And what about the Signal to Noise readership? They're based in Vermont. Everybody up there has guns! (Laughs)

JK: I understand you're rather fond of improvised music.

ES: It's always been close to my heart. When I taught myself guitar I would set up pedals that I made.

JK: That you made?

ES: Don't forget I was a science geek. I got an electric guitar when I was seventeen. I had been a classical pianist when I was six years old and had been playing concerts when I was eight. The stuff drove me crazy. I was playing Liszt and it gave me asthma. I almost burst a lung. There was a lot of stress. My parents expected me to be a Nobel Prize winning scientist and a concert pianist. When I got out of the house I stopped playing piano and began playing clarinet, figuring that would help me with my lungs. I got an electric guitar when I heard Hendrix on the radio. I started playing in a rock band and built my own fuzz box.

JK: Wow! You built your own fuzz box? Cool!

ES: It's a pretty simple design. I had no money to buy one. Then I got this National Science Foundation grant to be a junior scientist at Carnegie-Mellon University for the summer. I did some research to show how microwaves mutate fruit flies. Of course everything mutates fruit flies! (Laughs)

JK: And microwaves mutate everything!

ES: So I immersed myself in the lab and built fuzz boxes and played with tape echo units. And had a midnight to four AM slot on the radio station on WRCT and played Fugs records and Stockhausen and Ornette. Any weird things I could find.

JK: I understand.

ES: I'd make noise on the guitar. I didn't know it was improvisation. It was solipsistic. I'd lock myself in my room so I couldn't hear the yelling about the feedback and just play. Then I began reading books about music on Xenakis' Formalized Music because of the musical and the mathematical connection. I read Cage's Silence and Harry Partch, plus I was playing in weird rock and roll bands doing blues and Fugs covers. I tried to make the sounds I heard Albert Ayler and Coltrane doing except without the technique.

JK: Who did you find to play with?

ES: A buddy of mine was into Beefheart and Zappa, so the two of us played together. His father had the Coltrane record with Dolphy, Live at the Village Vanguard.

JK: And you heard "Spiritual."

ES: Exactly. Of course Coltrane blew me away but when I heard Dolphy's bass clarinet playing, it was like a voice from Mars. It was so vocal. It was like he was speaking in tongues. I knew I had to get one at some point. It was pure mystery. I was also listening to Ravi Shankar and other Folkways and Lyrichord records I got at the library.

JK: What happened to your science career?

ES: Well, when I saw what kind of lives scientists led, I didn't want to be one. I didn't know what I wanted to do but I knew I liked a lot of music, particularly non-Western music. I applied to Cornell and studied anthropology.

JK: Good move.

ES: Especially for attaining hallucinogens. I got involved in politics, anthropology and played in a rock band and took an electronics class with Robert Moog which was great. His factory was outside of Ithaca. I ended up going to Bard College. Roswell Rudd, who I knew about from Archie Shepp records, was teaching there. I studied Monk and Ellington and tried to develop my sense of being a composer. Now I feel that black dots on a piece of paper don't necessarily connote death (Laughs) but at the time it was such a European way of doing things and I wanted the music to be more alive and spontaneous. Again, coming from a mathematical and scientific background I was trying to figure out how to give a set of instructions to musicians so that the piece would be specific but could be manifest differently each time it was played. I also started fooling around with tape manipulation and ways of structuring improvisation. I'd jam with John and Evan Lurie (from the Lounge Lizards) who were in Roswell's class. I started playing saxophone and got back into the clarinet. Roswell was very encouraging about playing wind instruments. Then I went to Buffalo to do graduate studies and I ended up fighting a lot with Morton Feldman, who was my advisor. I love his music but he had an attitude. The short of it was he didn't buy improvisation. I ended up with a Masters' degree and that degree got me a twenty five cent an hour raise at the factory I was working at. Now that shows you the value of education, kids!

JK: For a guy who recorded for SST Records you're really quite a student. Didn't they give you an IQ test first?

ES: In those days, SST was great! Fred Frith, Henry Kaiser, Sonic Youth, Negativland.

JK: That's quite a leap, from junior scientist to hardcore.

ES: At the same time I was involved in a systematic way of acquiring and applying knowledge, I lived in a street culture, though I wasn't into hard drugs, I felt it was necessary to have empirical knowledge of them. So I know a bit about consciousness alteration and playing in rock bands and improvisation. It was a good balance to my formal education.

JK: Then you moved to New York for a "real" education.

ES: I moved to the city in '79 and began playing at the Tier 3 and the Mudd Club. It was a good time to be here. You had to get on and burn for twenty minutes and then get off the stage. I wrote an electronic opera called Innosense for three improvisers that was performed in a basement somewhere in post-apocalyptic New York. The characters came in at random and sang gibberish and bits of news or read from natural history textbooks.

JK: I used to have a punk/blues band called the Whirlin' Dervishes back in Minneapolis in '79. We'd rip through Robert Johnson's "Hellhound on My Trail" in one minute and thirty-eight seconds. So when I heard your band Terraplane it made perfect sense to me, to mix blues with hardcore and aspects of free jazz.

ES: In his book Black Music, Amiri Baraka, back when he was LeRoi Jones, said that no matter how far out free jazz got, you could still hear the blues cry in it and I agree. The vocal quality in free jazz always resonated with me. I'd been playing in a band called High Sheriffs of Blue in the early eighties and was looking for that meeting point, where I could bring the Albert Ayler/Ornette thing in on my horn. I formed Terraplane in '91 but we had some personnel problems and it just didn't gel. Now I've got Sim on drums who used to be with the Rollins Band, Mr. Bottom, David Hofstra on bass, and he also plays tuba. And Sam Furnace who is burnin', he turns up the heat with his saxophone. At the same time I was dealing with the logistical problems of how to organize large musical forces in New York with no time, money or place to rehearse.

JK: How large of a force are we talkin' about?

ES: 22 musicians.

JK: You're a hard guy to keep track of. You've got so many projects going.

ES: People dis me for that but I'm a composer. A composer isn't just a dead European guy with a powdered wig. As you can see I wear no wig! (Sharp says with a laugh, brushing his shiny shaved head with his hand). You get a sound in your ear and then you want to orchestrate it -whether it's for solo acoustic guitar or an orchestra.

JK: A lot of people are walkin' around just full of ideas but you've got an uncanny knack of conceiving a project and seeing it through - getting it performed and recorded.

ES: I came up through the mid seventies/punk/do it yourself independent music scene. I've always been a workaholic. It's what I love doing and I was independent from an early age I've had very little resources so I had to find a way to survive because I could never have a normal job. It would just kill me! So I've had to be extra resourceful. Plus record companies would never touch my music.

JK: As a composer don't you find being a multi-instrumentalist extremely helpful? Are any of your compositions ever dictated by a particular instrument?

ES: Actually my playing is an outgrowth of my compositional work.

JK: For me it's just the opposite.

ES: It used to be that way when I was into a more technical aspect of playing back in the early seventies. I loved Mahavishnu, Weather Report, Miles and Coltrane was a massively technical player. So I did a lot of woodshedding on my instruments. I used to write jazzy pieces for rock and funk bands that would come out of my instrumental technique. Now I'm not as good a player by any means. I've lost a lot of technique but I'm a much better musician because my hearing is better.

JK: Being a mandolin player and a multi-instrumentalist myself, I played a lot of folk, blues and rock. My interest in improvised music was originally sparked by Indian, Moroccan and Eastern European hoedown music I'd hear on old Nonsuch Records when I was a teenager. I got into jazz through guys like Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Don Cherry and Yusef Lateef, the fathers of world beat. But I listened to the Master Musicians of Jajouka much more than say Weather Report or Chick Corea.

ES: It was great meeting you backstage at the Jajouka show. We both knew Bachir (Attar). We both loved his music and the more we talked the more I thought, "yeah, we could do something."

JK: Hence Noodle Shop with Jonathan Segel (of Camper Van Beethoven/Camper Van Chadbourne fame) and Turkish percussionist Attila Engin.

ES: It was a great session. We had fun, trying a lot of different things, mixing all those traditional and folk sounds and we barely scratched the surface! I liked the fact that we didn't have any preconceived notions and we came up with some tunes. I always liked improvisation but I felt that musicians left to their own devices would fall into predictable patterns. We seemed to improvise song forms, creating short things, knowing there was a certain arc that would end over a course of five or ten minutes instead of just noodling.

JK: I have little patience for incessant noodling. As a songwriter and an arranger I constantly found myself being the anchor or straight man, which is pretty scary when you think about it.

ES: Jonathan really brought a strong sense of structure to the session too. And Bryce (Goggin) is an incredible engineer. He really pulled it all together. There was a certain perssure and intensity knowing that it was all being recorded live to two-track.

JK: And a guy none of us had met out in Missouri (Phil James) put up the money for the session. Unfortunately my ghaita (the Moroccan oboe played by the Master Musicians of Joujouka) was out of commission, so we'll have to try it again some time.

ES: Well, it was a good trip.