|

|

|

01 |

Albert's Shuffle |

|

|

|

06:56 |

|

|

02 |

Stop |

|

|

|

04:23 |

|

|

03 |

Man's Temptation |

|

|

|

03:26 |

|

|

04 |

His Holy Modal Majesty |

|

|

|

09:17 |

|

|

05 |

Really |

|

|

|

05:33 |

|

|

06 |

It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry |

|

|

|

03:30 |

|

|

07 |

Season Of The Witch |

|

|

|

11:08 |

|

|

08 |

You Don't Love Me |

|

|

|

04:10 |

|

|

09 |

Harvey's Tune |

|

|

|

02:07 |

|

|

|

| Country |

USA |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

CD Release Date: Oct 25 1990

All Music Guide

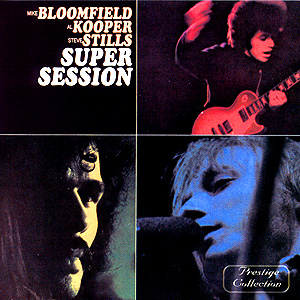

Al Kooper was the mastermind behind this appropriately named album, one side of which features his "spontaneous" studio collaboration with Mike Bloomfield and the other a session with Stephen Stills. The recordings have an off-the-cuff energy that displays the inventiveness of the two guitarists to best advantage. The best-selling recording of Bloomfield's career, it inspired the follow-up The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper. ~ Jeff Tamarkin, All Music Guide

Album Credits

Michael Bloomfield Primary Artist

Eddie Hoh Drums

Al Kooper Track Performer, Vocals, 12-string Guitar, Electric Guitar, Guitar, Keyboards, Ondioline, Organ, Piano, Horn Arrangements, Producer

Stephen Stills Track Performer, Vocals, Guitar

Steve Stills Track Performer, Electric Guitar

Harvey Brooks Bass

Barry Goldberg Electric Piano, Keyboards

Joe Scott Horn Arrangements

Fred Catero Engineer

Roy Halee Engineer

Michael Thomas Liner Notes

story as told by Al Kooper in his book

Backstage Passes and Backstage Bastards (c) 1998

"Mike Bloomfield was the son of an amazing businessman who created one of the most lucrative businesses in the history of America. Included in his father's giant restaurant supply arsenal were patents for the hexagon-shaped saltshaker with the steel circumcised top and the Jewish star pattern of holes, the cut glass sugar canister with steel doggy-door top, and the classic coffe-maker later appropriated by Mr Cofee for home use. The coffee-maker still bears the Bloomfield name today. Mr Bloomfield sold his business and patents to Beatrice Foods at its peak, and retired to a life of horseback riding and golfing while his two teenage sons went about the business of growing up in his extremely large shadow. My origins were comparatively humble is comparison.

However, there had been an amazing parallel between Mike Bloomfield's career and mine. We were both Jewish kids raised in big cities who were drawn to urban musicologies. We both came into the public eye from playing on Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited album (where we met). We both served apprenticeships in pioneer electric blues bands (Paul Butterfield/Blues Project). We both started relatively embryonic horn bands (Electric Flag/BS&T) and both eventually got kicked out of them. It seemed like destiny was throwing us together whether we liked it or not. We liked it.

I got him on the phone and it turned out he was not doing much of anything. "Why don't we go in the studio," I propose, "and just jam?" I don't think your best playing is on tape yet and this might just be the best way to get it there. Columbia will pay for it and release it and .... ya know....big deal."

"Okay," he said, "let's just do it in California."

We picked the sidemen (I chose bassist Harvey Brooks, Mike's recent bandmate from the Flag and my boyhood buddy; Bloomers chose Eddie Hoh, the Mama's and Papa's drummer known as Fast Eddie) and set the dates. I got all the proper permissions, filed all the correct paperwork, and away I went.

To make sure everyone was comfy, I commandeered a rent-a-house in LA. It was a nifty joint with a pool that fellow producer David Rubinson had been using while recording blues singer Taj Mahal. It had two weeks to run on Dave's monthly rental, and it seemed like a drag to just waste it. I got there a few days early and swan my New York ass off 'til Harvey and Bloomfield hit town.

Michael always had some kind of problem that he carried around with him; it's like a cross he enjoyed bearing (part of his American-Jewish suffering heritage). This time around he arrived with an ingrown toenail, which he kept insisting was gangrene. As soon as he walked in, he took the most expensive crystal bowl from the kitchen and soaked his big toe in it for an hour. His injured toe is immortalized in a photo on the back of the album for all you blues purists and foot fetishists.

That first night in the studio, we got right down to business. Barry Goldberg, also late of the Electric Flag, came down and sat in on piano for a few tracks. We recorded a slow shuffle, a Curtis Mayfield song, a Jerry Ragovy tune, a real slow blues number and a six-eight fast waltz modal jazz-type tune, and in nine hours had a half an album in the oven.

Jim Marshall and Linda Rondstadt came down to visit, and Jim snapped away on his Nikon documenting the evening on film, while Rondstadt quietly sat in the corner watching. There was a real comfortable feeling to the proceedings, and while listening to one of the playbacks I noted that I had gotten the best recorded Bloomfield and, after all, that was the whole point of this exercise. We piled into the rent-a-car and made it back to our palatial surroundings, crashing mightily with dreams of finishing the album the next night.

What happened next is one of the quirks of fate that you can't explain, but you never question in retrospect. The phone started jangling at 9am and it was some friend of Bloomfield's asking if he made the plane 'cause she was waiting at the airport to pick him up.

"Huh? Michael's fast asleep in the next .... Hold on," I said, doing a gymnastic hurdle outta bed into the next bedroom to find... an envelop? And, inside:

'Dear Alan, Couldn't sleep ... went home.... Sorry' "

SHIT!

Raced back to the phone.

Nobody there.

I got half an album, studio time, and musicians booked, and this putz can't sleep in the $750. a month dungeon with the heated pool and the crystal toe soaking bowl.

My first corporate hassle.

"Well Clive, of course I'm aware of the costs, but he couldn't sleep. I mean haven't you ever had insomnia?" No way that was gonna work.

It was 9:15 in the morning and mind and ulcers were having a foot race for the finish line. I was actually on the verge of packin' it in myself, but a cooler part of me fortunately prevailed. I methodically made out a list of all the guitar players I knew who lived on the West Coast. At noon, I started callin' 'em. Randy California, Steve Miller, Steve Stills, Jerry Garcia. By 5pm I had a confirm on one player and left it at that. Once again, fate stepped in to save my ass, this time in the persona of Steve Stills, also unemployed by the breakup of his band, Buffalo Springfield.

Steve was primarily known as a singer-songwriter, and mainly on the West Coast, but I knew he was a hot guitar player and I was more than willing to give him a try. (Besides I didn't have a choice, did I?) At 5pm I tried Ahmet Ertegun in New York. Steve was signed to Atlantic, and you just don't make records for other labels without permission - another corporate hassle. Steve was one of my favorite singers and to have his voice on the album would have upgraded it two hundred percent, but at that point I felt it would have endangered the release of the album by tying up Atlantic and Columbia in one of those red tape battles that pencil pushers are so fond of. It's bad enough he was gonna play without permission, I thought. Let's leave it at that and cross our fingers, hoping Atlantic will let us just use his fingers. In retrospect, the negotiations included a swap so that Graham Nash (signed to Epic/Columbia as a member of The Hollies) was allowed to record for Atlantic on the first Crosby, Stills and Nash album in exchange for Stills appearance on our album. Steve had just gotten his first stack of Marshall amps and was chompin' at the bit to blast his Les Paul through 'em.

At seven that evening Steve, Harvey, Eddie and yours truly sat down at our instruments and

stared at each other.

Now what?

One of the songs I wanted to do was inspired by an English album I had recently acquired. It featured the performance of a spectacular young organist named Brian Auger and a trendy jazz singer named Julie (Jools) Driscoll. The album contained their version of Dylan's "This Wheel's on Fire," which was a top single in Europe, and a rambling version Donovan's "Season of the Witch" that I had heard coming out of every shop on Kings Road when I had recently visited London. I thought it would be nice for us to do it, 'cause it provided a lot of room for improvisation and everyone already had the basics of the song down. We did two takes straight off, and the version we kept was edited from the two. Since this was the first big-time record I'd ever produced, I was kinda green in some areas. Editing was one of them. During "Season of the Witch" there are a few edits between takes 1 and 2. The problem is that the two takes were different tempo's. I didn't care. I just hacked away and got the bad parts out and the good bits in. So at every edit point the tempo changes. Either you hear those edits or you think we were musicians so attuned to each other that was sped up and slowed down to perfectly together. Not!

When I'd played on Highway 61 Revisited, we'd cut some songs two or three times with different arrangements each time. One such song was Dylan's "It Takes a Lot to Laugh It Takes a Train to Cry." We originally recorded it as a fast tune, but Dylan opted for the slower version cut a few days later as the keeper for his album. I pulled out the fast arrangement and taught it to everyone and we had song number two.

A staple number in Buddy Guy's and Junior Wells repertoire was Willie Cobb's "You Don't Love Me." It was usually done as a shuffle, but I found it lent itself well to a heavy-metal eighth-note feel. Later, when I mixed the album, I put the two-track mix through a process called "phasing" that gave it an eerie jet-plane effect.

It was 3am and we had three tunes under our belt, leaving us one or two tunes short of an album side. We racked our brains, but to no avail. Then Harvey said he had just written a tune that we might like, and played it for us on the guitar. We did like it and that became the final tune on the album. It was called "Harvey's Tune" at that time, but it was later included with a lyric on an Electric Flag album as "My Woman Who Hangs around the House." Nice title Harvey.

I left for New York, a day later with the tapes and continued working on the album there. I put on all my vocals, added some horns for variety, and mixed it slowly and deliberately. After all, this was my debut as a producer, and I wanted it to be as competent as possible. I played it for the big boys at CBS and they thought it was okay enough to release. Bruce Lundvall, a kindly VP (later to become president of Blue Note records) named the collection Super Session. Six weeks later it was in the stores.

Fully aware that this was just a furthering of the Grape Jam concept, and considering the relative infamy of Bloomfield, Stills and myself. I didn't delude myself that the album was going straight up to number one or anything. It was merely something for me to do while I learned my new craft. I was back in LA the day it was released, and ambled into Tower Records to see the initial reaction. I swear they were sailin' 'em over the counter like Beatles records!

In a matter of weeks, it was in the Top Twenty and finally peaked at number 11. But that was plenty. This was a first for me. It only cost $13,000. to make, and soon it was a gold album (for sales exceeding 450,000). I found this particularly ironic. All my life I'd busted my ass to make hit records. Now me and these two other goons went into the studio for two nights,screwed around for a few hours, and boom, a best-seller.

In retrospect, I think that's what sold the record. The fact that, for the first time in any of our careers, we had nothing at stake artistically. Also, we had brought another ounce of respectability to rock and roll by selling a jam session as "serious" music, something that had only been done in jazz circles up 'til then. All of a sudden, I had the respect of the CBS shorthairs. Shortly thereafter, because of the tremendous success of Blood, Sweat & Tears' second album, my BS&T album turned gold, and then there were two (gold albums, that is). In retrospect, I might add that as of this writing, I still have not received one cent in royalties for these albums that sold millions of copys.

With Super Session's success, things became a lot more comfortable around the corporate HQ. Instead of just being the company freak, I was the company-freak-with-the-number-eleven-LP-on-the-charts, an important distinction. I had already been through three frightened "straight" secretaries (who quit, or asked to be transferred), and I still don't understand the ramifications of the "paperwork system."

As Super Session began making it's way down the charts, I needed some product on the street. I got a bad case of commercial fever and decided to cut a follow-up to our quasi-hit. One of the only criticisms of SS was that it was a studio album and, therefore, "uninspired." Always one to want to shove it up critics' asses, I decided to cut a live jam album, possibly at the Fillmore in San Francisco. I called Bloomfield and he said sure, I owe you one for (for when he snuck out of the first album).

This time he chose his friend and neighbor, John Kahn, on bass, and I selected Skip Prokop on drums. Prokop had just quit The Paupers , a Canadian group I was friendly with. I couldn't get Steve Stills because of prior commitments on his part - but mostly on instruction from higher-ups, who evidently were still embroiled in the legal aspects of our last venture." . . .

Michael Bloomfield - Guitar, Guitar (Electric), Keyboards, Vocals, Performer

Al Kooper - Organ, Guitar, Piano, Guitar (Electric), Keyboards, Vocals, Guitar (12 String), Producer, Performer, Ondioline, Horn Arrangements

Stephen Stills - Guitar, Vocals, Performer

Barry Goldberg - Keyboards, Piano (Electric)

Michael Thomas - Liner Notes

Harvey Brooks - Bass

Fred Catero - Engineer

Roy Halee - Engineer

Eddie Hoh - Drums

Joe Scott - Horn Arrangements

Steve Stills - Guitar (Electric), Performer