|

|

|

01 |

Giddyup |

|

|

|

00:18 |

|

|

02 |

Frankie Doris |

|

|

|

02:52 |

|

|

03 |

Money On My Mind |

|

|

|

03:31 |

|

|

04 |

Don't Let The Devil Ride |

|

|

|

02:10 |

|

|

05 |

Keep Your Lamp Trimmed And Burning |

|

|

|

02:53 |

|

|

06 |

Capitaine |

|

|

|

02:06 |

|

|

07 |

Santoro |

|

|

|

02:36 |

|

|

08 |

Fire On The Radio |

|

|

|

00:27 |

|

|

09 |

Fire |

|

|

|

05:09 |

|

|

10 |

Bb |

|

|

|

02:18 |

|

|

11 |

Downhome Prelude |

|

|

|

00:09 |

|

|

12 |

Downhome Sophisticate |

|

|

|

03:17 |

|

|

13 |

Sista Rose |

|

|

|

06:28 |

|

|

14 |

Black Maria |

|

|

|

04:32 |

|

|

15 |

Chinook |

|

|

|

02:30 |

|

|

16 |

Money Eye |

|

|

|

04:04 |

|

|

17 |

Where The Yellow Cross The Dog |

|

|

|

01:53 |

|

|

18 |

F'shizza |

|

|

|

05:42 |

|

|

|

| Country |

USA |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

Date of Release May 7, 2002

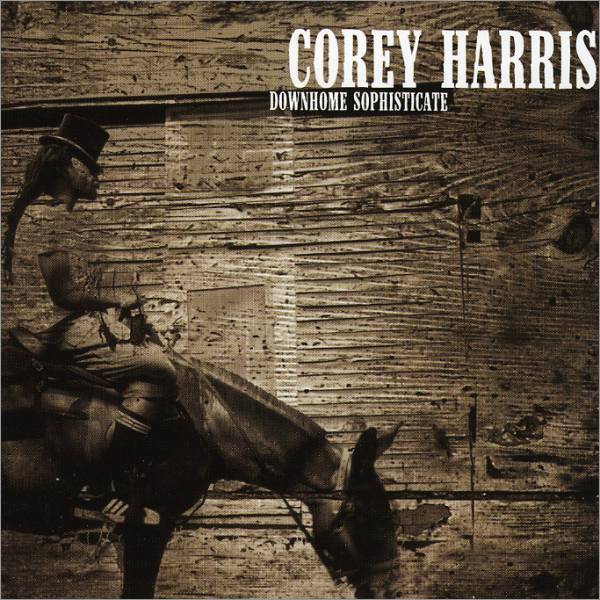

Few artists reflect the breadth of black music as vividly as Corey Harris, who performs at the peak of his strength throughout Downhome Sophisticate. The overall feel is rural, with plenty of slide guitar slithering over raw, live rhythms. The hooks have a timeless feel, as on "Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning," with its rootsy gospel vocal motif and an implied handclap beat over a "My Sharona" hook. But Harris nods as well toward acoustic folk-blues, softened and broadened on the solo track "Capitaine" by an almost John Redbourne feel (which owes a lot in itself to Son House). Instrumental tracks evoke images nearly as clearly as those with words; the jump boogie bounce of "BB" paints a picture of a Southern roadhouse on a Saturday night. But when Harris adds lyrics they enhance this eloquence, as on "Fire," whose references to Babylon, bloodshed, and perditional flames project an ominous, apocalyptic power. It's an easy leap for Harris from folklore to urgent urban settings; his depiction of a police car as a fearsome, prowling Biblical beast makes "Santoro" especially disturbing. The fact that Harris also borrows from Mexican and Latino traditions, especially on "Sista Rose" and the sensuous "Black Maria," makes the point that African-American culture, the center of Western pop, abuts multiple styles and is able to draw from each with equal ease. In the end, the title says it all: This is music both primitive and elusive, easy to absorb and more difficult to play than it seems. - Robert L. Doerschuk

John Gilmore - Drums

John d'Earth - Horn

Olu Dara - Trumpet

Vicki Brown - Bass

Stephen Van Dam - Engineer

Corey Harris - Guitar, Producer, Art Direction, Lap Steel Guitar, Concept

Fred Kervorkian - Mastering

Mark Maynard - Horn

Jeff Juliano - Engineer, Mixing

Jeff Decker - Horn

Wyndsor Taggart - Design

Mark Henry - Producer, Mixing

Rob Jackson - Rhymes

2002 CD Rounder 613194

By: Neil Strauss "New York Times"

Corey Harris makes a good first impression. The first time I saw him was in the tiny back room of a club in New Orleans. He was sitting on a stool, a battered National steel guitar in his hand. His shirt was unbuttoned and sweat was dripping off his beard onto his chest. Each time he struck the rattling strings, tapped his ragged brown shoes on the dirty concrete floor or coaxed a phrase out of some place deep inside his gut, the audience's sense of place and time disappeared a little. Until all they were left with was this incredible musician who had somehow plugged himself not just into the deep-running waters around the Mississippi Delta but also the equally deep and raging currents of his own blood, of the journey from freedom to slavery to freedom of his own ancestors, whose roots he has spent much of his life researching. Corey Harris makes an even better second impression. Talking with him opens up a world of experience.

He has a degree in anthropology; he studied Pidgin-English on a Watson Fellowship in Cameroon, West Africa; he drove throughout the South playing guitar; he taught middle-school French in a small Louisiana town; he's led students on public service projects in New Orleans. He listens to everything: rap; spirituals; klezmer; Indian sitar music; Hawaiian slack-key guitar; French dance-hall tunes and Malian guitar players. His ears are amazingly wide open. And in the past year the world's ears have been opening to his music. Until just a couple of years ago, Harris' main concert venue was the streets. Now, at 28, he's played at festivals all over Europe, appeared in Japan with B.B. King and Buddy Guy, and toured across America as an opening act for not only B.B. and Buddy, but also for Natalie Merchant and The Dave Matthews Band, gaining exposure to a pop audience is an extremely rare opportunity for an acoustic blues musician.

He's also grown remarkably as a songwriter, striking an equal and effortless balance between his own songs and the blues canon on this album, his second for Alligator. On his first, Between Midnight And Day, there were only three originals and there was a kazoo instead of a brassy back-up band. Harris' life has turned completely around in the past year. For the first time in his life, he's actually making a living at concert halls. And what does he want to do now? "Play for school children," he says. Harris is a beautiful contradiction, and it shows in every aspect of this album. Beginning with the titled, Fish Ain't Bitin', (Real Audio) a bad-luck expression from a man who's had almost nothing but good luck (at least career-wise) lately. Then theres the first few bars of the first song, High Fever Blues. It begins with a sparsely plucked guitar, which is suddenly answered by a melancholy blast from a horn section that seems to have wandered over from a street parade in Harris' current home, New Orleans. Forget authenticity; Harris is going for a sound true to himself. To top it off, the high fever Harris sings about with such conviction and desperation is the chicken pox. "You know that high fever makes a rich man poor," he sings with a mix of humor and earnestness on spending a workday in the sick bed. This kind of unpredictability continues throughout the album.

Though some listeners peg Harris as a Delta blues purist playing like he's a contemporary of Robert Johnson or Son House, it's too easy an explanation for an album with roots this complex. That's not to say that Harris isn't a believer in tradition. He is staunchly so, especially when those traditions have to do with family, the blues, reggae, Africa, education or hundreds of other things. But he's only interested in tradition insofar as it enables him to put the present into focus. That may explain songs like the police corruption lament 5-O Blues, which mixes contemporary slang with a guitar-picking style at least 70 years old. Yet this album is not a hybrid in any self-conscious way. The percussion may vary from Harris' stolid foot-tapping to the deep-barreled rhythms of the djun-djun, a Malian bass drum. But, considering Harris' wide range of interests, the sound is remarkably consistent and unforced. "I don't like to be all over the map," Harris says. "But I don't need to tune out things either. I leave room in the music for little bits of things to influence it. Sometimes I might say something I heard on a hip-hop record. It's about bringing what Iнve experienced into my music and just being true to how I express myself naturally." Take the albums title track, Fish Ain't Bitin', which begins with a delivery that sounds more like radical 60s poetry (a la The Last Poets). That is, before the tuba kicks in. "As a title, Fish Ain't Bitin' came to me from thinking about the situations in rural areas," Harris says. "I lived for a while in rural Louisiana and saw how people have problems with the environment, education, unemployment and just having something as simple as having an ambulance get you if you have an accident. So I summed it up: Fish Ain't Bitin'. There is a lot of things to be had, but they're not reaching the people they need to reach. The song also comes from me being a kid, going down to East Texas to fish for catfish on family land. Nowadays those kinds of interchanges and being outdoors with your family, old people telling stories are very precious. It's special when they happen, the simple things. Harris' first album, Between Midnight And Day, was so simple it took only six hours to record. This one took a little more time but not so much that the music loses its immediacy. The first session was recorded during a weekend in October, 1996. Harris waited until December to return for a final two days of recording and mixing. After all, why rush timeless music? Neil Strauss, The New York Times

For Myles, Corey Harris would like to thank The Creator, The Ancestors, my family, Kore, Sharon and Jamal, Shane and Ginger, Josephi, Harry, Wolf, Charles, Tuba and Chris. Thanks also to Nora and everybody at Alligator, Dave at Ultrasonic and la famille Crumb. JAH loveth the gates of Zion more than all the dwellings of Jacob.(Psalm 87). Larry hoffman wishes to thank Kore Obialo, David Farrell, Bruce Iglauer and staff at Alligator and Kurt Johnson.