|

|

|

01 |

21st Century Schizoid Man including Mirrors |

|

|

|

07:23 |

|

|

02 |

I Talk to the Wind |

|

|

|

06:06 |

|

|

03 |

Epitaph including March For No Reason and Tomorrow And Tomorrow |

|

|

|

08:48 |

|

|

04 |

Moonchild including The Dream and The Illusion |

|

|

|

12:12 |

|

|

05 |

The Court Of The Crimson King including The Return Of The Fire Witch and The Dance Of The Puppets |

|

|

|

09:23 |

|

|

|

| Country |

United Kingdom |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

King Crimson

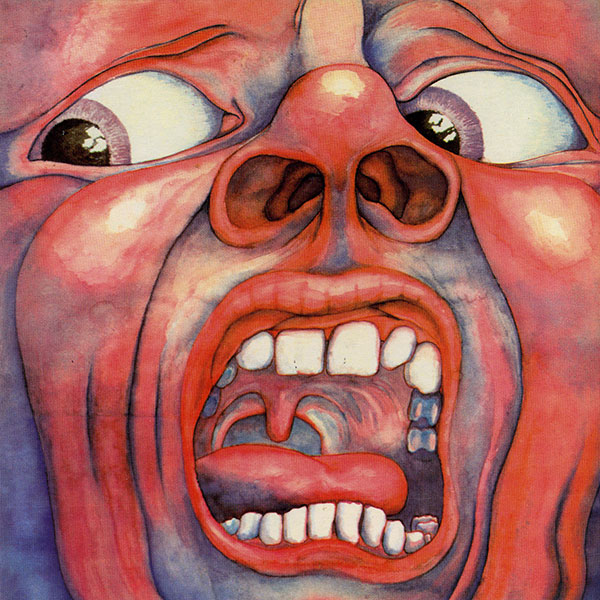

In the Court of the Crimson King

(an observation by King Crimson)

Robert Fripp : Guitar

Ian McDonald : Reeds, Woodwind, Vibes, Keyboards, Mellotron, Vocals

Greg Lake : Bass Guitar, Lead Vocals

Michael Giles : Drums, Percussion, Vocals

Peter Sinfield : Words and Illumination

Produced by King Crimson

THE DEFINITIVE EDITION

Re-Mastered by Robert Fripp & Tony Arnold 1989

786 485 2 EGCD 1 (P)+(C) 1969 EG Records Ltd.

Bob Eichler:

Put me down as one of the heretics who think this album is a little overrated, both in its title of "first prog album" (there are plenty of earlier albums that could arguably be called prog) and in the songs themselves. The only song from this disc that I think is an absolute, must-hear classic is "21st Century Schizoid Man", and even that one has much better live versions available. The rest of the disc is way too lightweight for Crimson, sounding rather soporific and dated.

As everyone else mentions, this is an album that all prog fans should hear for historic purposes if nothing else. Just don't expect too much. And for those who don't like the "pointless noodling" section of "Moonchild" - try the Frame By Frame boxed set version where that bit is edited out.

Heather MacKenzie:

For some reason I lump this in with the output from the '72-'74 phase of the band; not quite as avant-garde as that material, but equally progressive, exciting, and somewhat dark.

It's hard to decide if the original "21st Century Schizoid Man" is better than the later live versions, or not. Generally the live versions are crushingly heavy and chaotic; but the original studio version, while not quite as aggressive, has other benefits, mainly the extended guitar solos not duplicated live: howling, angular, eerie, perfectly capturing the emotion expressed by the cover. What I find most appealing about this is the perfectly fluid mix of classical, jazz, and rock within one piece. One moment is high-tension dramatics such as the rising pitch motifs of the main guitar/sax riffs, and running guitar lines. Another is all graceful staccato syncopation, crescendo and decrescendo. And yet another, chaotic noise, another, almost bebop sounding riffs. Fascinating.

"Epitaph" is also a Crimson classic and I don't find it hard to see why people consider it so, with the dark acoustic guitar arpeggios, swelling volume dynamics, epic Mellotron, and rolling drums; especially interesting is the funeral march section with the gloomy woodwinds and sinister guitar chord slashes.

Although this album influenced symphonic prog bands, there are distinct differences. This album is, compared to the (more popular) symphonic rock that it influenced, less precious and less whimsical, and is darker, jazzier, and noisier, with leaner/shorter compositions (between the five and ten minute mark).

Sean McFee:

As we all should know, this is the album that is widely considered as having launched the progressive rock movement. I see no reason to disagree with this assessment, for as some proto-prog efforts surely predate this album, this is the album that crosses the line into full-blown prog and influenced most of what was to come from the main symphonic bands.

Every aspect of this album can be looked at for the way that it set a trend to be followed. The potent, statement-making artwork. The fantasy-laden, grandiose and sometimes tedious lyrics. The transitions from soft, pastoral sections to dark "orchestral" fanfare (simulated on Mellotron of course) or frenetic, jagged instrumental workouts. The construction of longer, "epic" pieces from disparate themes. And, one could remark cynically, the inclusion of a big duff track ("Moonchild") on an album of otherwise good material which would plague many groups, particularly Genesis.

So where does that leave this album? Judging by the merits of its influence, it simply should be heard. Judging solely by the content, free of context, it's somewhat less essential but is still worth the price of admission for "21st Century Schizoid Man".

Joe McGlinchey:

Some may find a less-than-perfect rating to be heresy, as this is regarded as one of (if not the) premiere landmarks of the progressive rock genre. Well, I like this album a lot, but its staying power hasn_t been as strong to me as later Crimson material. The only song here that I ever play nowadays is "21st Century Schizoid Man." The other tunes, while undeniably sumptuous bits of melancholy ("Epitaph," "Moonchild," verses of the title track) or bedazzlement (the chorus of the title track) saturated with Ian Macdonald's mellotron, also have rather conventional guitar progressions and structures that I find to be a bit over-repetitive. Also, I've never been a big fan of Peter Sinfield's lyrics. There are some lyricists who I think did that sort of style in a much more creative and exciting way (the Incredible String Band comes to mind). But with the exception of "Schizoid Man," where Sinfield hits the bullseye, I find most of his wordscraft not very interesting and often even bloated to an unforgiveable degree. Apart from these criticisms, though, a great debut and love that cover!

Eric Porter:

Don't go away just yet. I know what you are thinking: "everyone gives this one a great rating, so why read another review?". This really was a defining moment for the genre. Crimsons sound was unique, aggressive at one moment with "21st Century Schizoid Man" and atmospheric and full of subtleties on the next like "Moonchild". This does not get five stars for what it was, though; I think it still warrants five stars today. Sinfield's surreal lyrics, a classic album cover (that a CD package can never do justice to), and music of incredible quality. The jazzy wild "21st Century Schizoid Man" would still slay an audience today with its ferocious attitude and the screaming sax lines of Ian McDonald. The band then shifts gears completely with the pastoral "I Talk to the Wind" using acoustic sounds, flutes, woodwinds, and a great melody. "Epitaph" is an emotional powerhouse, with an incredible vocal performance from Greg Lake. It is dripping with Mellotron laden passages and one of their most dramatic songs. "Moonchild" may be the one song that everyone may not enjoy with its experimental mid-section using vibes and percussion to create some different atmospheres and possibly influenced by the jazz experimentation of the times. The title track, again using high drama, closes out the CD. The song again goes from soft subtle passages to the uplifting and powerful chorus. Even if you are not as enamored by this music as I am, as a progressive fan this is a must have. This CD is one of the high points in progressive music and Crimson's career.

Brandon Wu:

It's debatable whether this was the album that truly launched the progressive rock movement as we know it (I would say no), but there's no denying that this is a landmark release, and a classic to boot. Though it's not the King Crimson album that gets the most spin time in my CD player, there are some fantastic moments on here. The smoking, distorted jazz-rock of "21st Century Schizoid Man" is a crowd favorite to this day at live Crimso shows; the epic, Mellotron-soaked adventures "Epitaph" and "The Court..." virtually kicked off the symphonic-rock genre; and the flute-led "I Talk to the Wind" wallows in a strange, enchanting beauty. I might argue that the title track is too repetitive, the opener "Schizoid Man" is too distorted and demented, or that the jam that forms 75% of "Moonchild" is boring as hell. But while all those criticisms are true to a certain extent, that's missing the point - anyone that calls himself a prog fan must give this disc a listen, as it's not only a great album, but also a piece of history and a true monument of the genre.

conrad

When I first purchased this album a number of years ago, I had already been listening to the other classic progressive rock groups for some time. This album didn't grab me at first, and I was hard pressed to see what all the fuss was about. After all, I'd heard it all before. The mellotron arrangements and gentle flute I had heard Genesis do, the silly section of pointless meandering at the end of Moonchild I had heard in "Take a Pebble" by ELP, and I had even heard the song "Epitaph" on Welcome Back My Friends... (again by ELP). But that's just the point. This is the album that set the agenda for the next five years, which were the golden age of progressive rock.

So this is an important album, you get that. The next question is, "Is this album worth buying for somebody who is not interested in its historical value?" The answer, for me, is a qualified yes. I prefer most of the classic progressive rock albums to this one, but that doesn't mean that it isn't a good album. The songwriting is strong, and aside from ten minutes of "Moonchild" there is nothing I would consider mediocre. The moods created are very effective, and reminiscent of what was to come, though King Crimson had an agressive streak that nobody was quite able to match.

Even with the freshness that this album posessed in 1969 gone a little stale, this is still a worthwhile album. If you don't have it, get it straight away for its historical value, or buy it after Red for its musical value.

7-28-03

http://www.interx.net/~jgreen/

In the Court of the Crimson King

Date of Release 1969

The group's definitive album, and one of the most daring debut albums ever recorded by anybody. At the time, it blew all of the progressive/psychedelic competition (the Moody Blues, the Nice, etc.) out of the running, although it was almost too good for the band's own good - it took them nearly four years to come up with a record as strong or concise. Ian McDonald's Mellotron is the dominant instrument, along with his saxes and Fripp's guitar, making this a somewhat different-sounding record from everything else they ever did. And even though that Mellotron sound is muted and toned down compared to their concert work of the era (see Epitaph, below), it is still fierce and overpowering - coupled with some strong songwriting, most of it filled with dark and doom-laden visions, the strongest singing of Greg Lake's entire career, and Fripp's guitar playing (a strange mix of elegant classic, Hendrix-like rock explosions, and jazz noodling), the mix was overpowering. Fripp would be the only survivor on their subsequent records. Note: Be sure the CD you buy indicates it was made or distributed by Caroline Records - earlier versions sounded awful. - Bruce Eder

21st Century Schizoid Man

AMG REVIEW: King Crimson enjoyed a lengthy, varied career throughout their various incarnations and managed to maintain critical favor even while progressive rock as a genre came to be inextricably linked (in many cases, unfairly) with the idea of indulgent excess. Yet their signature song has always remained "21st Century Schizoid Man," the very first track from their 1969 debut album, In the Court of the Crimson King. Built around a lumbering, heavy main riff that alternates with the verses, swirling production, and an explosive, intricate middle section of up-tempo jazz-rock, "21st Century Schizoid Man" set the general tone for much of the rest of the group's output, regardless of lineup: their virtuosic musicianship was not just an end in itself, but enhanced the often edgy, disorienting feel of the music. Lyrically, the song evokes a dystopian future that bears a strong resemblance to the unstable late '60s: full of war ("innocents raped with napalm fire"), torture, political assassination, starvation, and greedy consumerism ("nothing he's got he really needs"). The fear is that the only way to deal with life in such a world will be through frantic paranoia, that the larger picture cannot help but have a psychologically damaging effect on the individual. It's an unforgivingly dark, humorless worldview, to be sure, yet "21st Century Schizoid Man" is based a great deal more on real-world issues than the subject matter of many other prominent art rock bands of the '70s, lending an evocative drama to the group's tense instrumental interplay. As the song begins, Ian McDonald's overdubbed horns wail plaintively above the ominous rumble of the guitar/bass foundation, and harmonizations of the otherwise simple riff bounce around between his multiple instrumental voices. Both Greg Lake's vocals and Ian McDonald's backing Mellotron chords on the verses are distorted, wafting toxically above periodic bursts of activity in the rhythm section. The middle section of the song, called "Mirrors," reflects just how tense and off-kilter the mind of a 21st century schizoid man is; the jazzy main riff of this section is taken at a furious pace and repeated over frantic, disjointed rhythms (virtuosically executed by bassist Greg Lake and drummer Michael Giles). There follows an extended solo by guitarist Robert Fripp, who uses different amplification effects and plays sharply angled, almost atonal melody lines, creating dissonance and texture instead of simply displaying his technique. After another run through the main "Mirrors" riff, there's an intricate unison section in which all the lead voices articulate busy, lightning-quick lines with start-stop rhythms. There's an abrupt return to the much slower original song structure for the final verse, after which the music dissolves into an apocalyptic chaos, just as the psyche and the society of the title character do. Overall, the song is a powerful statement that musicians of lesser technical ability simply wouldn't imbue with nearly as much resonance; it's one of progressive rock's finest individual moments. - Steve Huey

Epitaph

AMG REVIEW: Rock history, like all kinds of history, tends to be divided after the fact into winners and losers. Among most rock critics evaluating progressive rock bands, King Crimson has been tagged as winners and the Moody Blues as losers. The fact is, though, that in their early days, King Crimson could sometimes sound rather close to what the Moody Blues were doing in the late '60s. Nowhere was that resemblance stronger than in "Epitaph," the portentous nine-minute cut that closed side one of ^In the Court of the Crimson King: An Observation y King Crimson. This is not to say that this sounds like a Moody Blues copy, or that being like the Moody Blues is always a bad thing; it's just an observation. The song begins with a dramatic drum roll and pseudo- orchestral sweep of somber melody. This gives way to a rather folky verse - many prog rockers used folk-rockish structures as the backbone of some of their material - in which the singer records rather gloomy images of nightmares, death, and decay, accented by doom truck drum thumps. The singing becomes more passionate on the following verses, leaping a whole octave upward, as the vague poetic words continue to evoke dark places where nothing is known and threat is looming. This leads up to a more dramatic chorus in which the words are punctuated by more spacious pauses and brief dabs of notes before concluding on a more thunderous, apocalyptic note, expressing the singer's fear that things aren't going to turn out all that well. Cheerful stuff indeed, but the tune is pretty attractive. The arrangement is good too, with Robert Fripp's guitar undulating like a weeping willow and Ian McDonald's Mellotron adding a layer of fear. An extended instrumental break finds the reeds and woodwinds playing off particularly gloomy guitar chords, the stop-and-start beats and frequent beats mirroring the oncoming crawl of a grim reaper. The extended fadeout on the last part of the chorus pushes the Mellotron up front to seal the spooky, desolate atmosphere. - Richie Unterberger

I Talk to the Wind

AMG REVIEW: King Crimson, it is not often noted, had some folk and folk-rock influences in their very early days (and the Giles, Giles & Fripp collaborations predating King Crimson). "I Talk to the Wind" is the track that most reflects these folk influences and the influence of co-songwriter Ian McDonald (only a bandmember for the first album) in particular. Coming right after the assaultive jazz- prog rock of "21st Century Schizoid Man," the first track on their debut album ^In the Court of the Crimson King: An Observation y King Crimson, this gentle, subdued folky ballad was quite a contrast and served notice that King Crimson was more versatile than your average new band. McDonald's lilting recorder carries the song's principal pastoral riff, leading into a typically late-'60s lyric of a passive, disoriented protagonist, not so much making comments as recording impressions and reveling in ambiguity. The harmonized, slightly jazzy vocal melodic lines, though, were lovely, leading to a slightly more up-tempo, tensely pensive verse, lamenting (or perhaps merely just noting) that the lyrical observations were blown away, unheard, by the wind. The version on King Crimson's album is the only one that most listeners are familiar with, but actually the song had been recorded at least a couple of times in 1968 by embryonic King Crimson lineups. One version, a more genteel arrangement featuring McDonald, Robert Fripp, Michael Giles, Peter Giles (who dropped out before King Crimson's first album), and ex- Fairport Convention singer Judy Dyble, showed up on the 1975 compilation The Young Person's Guide to King Crimson. This, and a second 1968 recording featuring the same lineup minus Dyble, appear on the archival Giles, Giles & Fripp CD The Brondesbury Tapes. - Richie Unterberger

The Court Of The Crimson King including The Return Of The Fire Witch and The Dance Of The Puppets

AMG REVIEW: "The Court of the Crimson King" was the grand finale to King Crimson's epochal debut album, ^In the Court of the Crimson King: An Observation y King Crimson. Although the song is really not at all typical of what most of King Crimson's records contained - particularly since guitarist Robert Fripp has been the only member from the lineup on that album to play on most of the group's subsequent recordings - it remains, justifiably, their most famous song. The track wastes no time pulling out the stops, starting with a grand, clenched-teeth Mellotron riff anchored by Michael Giles' always varying, underrated drum beats, and the drama is heightened by a turnaround (inspired by James Brown, of all people) in which the Mellotron slowly creeps up the scale until it gets back to where it started. As the intro fades out, a folky verse starts that's really not all that different from a typical classy late-'60s Donovan tune. (Lest some find the Donovan citation an affront, let it be noted that early King Crimson regularly covered Donovan's "Get Thy Bearings" in concert.) The lyrics evoke a medieval royal court and not one that's entirely welcome, with its images of a black queen, funeral march, and fire witch. The vocals become more intensely dramatic - portentous, pretentious even - as the singer announces the court of the crimson king, leading into a death-mask wordless harmonized vocalization of the grinding theme introduced in the opening instrumental section. Cleverly, the band varies the instrumentation and tempo subtly from verse to verse with thoughtful skill beyond most folk-rockers or prog rockers - Michael Giles' stuttering drum rolls being particularly excellent. The verses are interrupted by instrumental breaks which, again, are quite different from each other, though they adhere to the same tune: one glides like a kite set free over fields, another is a pastoral respite that accelerates ominously near the end. The macabre mood peaks in the last verse, where the wordless turnaround eventually comes to a tumbling halt, followed by a sudden optimistic chord and Aeolian vocal as if heralding the appearance of a sudden shaft of sunlight in the dismal court. But it's a false ending, some percussive tinkles leading into a downright goofy reiteration of the main theme by recorder, as if to mimic the dances of the puppets described in the song. An especially booming drum pattern leads the band back into its most crazed, violent restatement of the main theme, this time wholly instrumental, with some of the greatest, chilliest Mellotron ever played on a rock record (by Ian McDonald). The impression here is of a magical court on the verge of teetering amok, especially with the near-berserk keyboard washes of the final bars before it comes to a cold end. The nine-minute "The Court of the Crimson King" may have some of the bombast and pretension that early progressive rock in general is accused of purveying. But few, if any, early progressive rock tracks were as powerful, perfectly evoking the magical yet ghastly faces and artwork adorning the album sleeve. - Richie Unterberger

A Young Person's Guide to All Things Crimson, Part 1:

The Early Years

By Clayton Walnum

King Crimson has had a long and illustrious career over which the band, in its many incarnations (Robert Fripp is the only member who has participated on every album), has released some of the most challenging and thought-provoking rock music known to man. Although often relegated to a cult following, King Crimson is still respected as one of the original "big six" of progressive music's early days, along with Yes, Genesis, Pink Floyd, EL&P, and Gentle Giant. Moreover, they're the only band from progressive rock's golden years that has retained their artistic vision to this day, never placing a desire for commercial success over the integrity of the music, never allowing critics to affect whatever direction the band chose to take at each step along its career.

Although King Crimson has been around since the genesis of progressive rock (some would say that KC's In the Court of the Crimson King was the first progressive rock album ever released), and although the group is still active today, many fans of progressive music have not kept up with this extraordinary group or may have neglected the band's early releases. In this two-part article, I hope to rectify both of these cases, by providing an album-by-album overview of this groundbreaking group's studio releases. (We won't discuss live albums, of which King Crimson has released more than just about any other artist outside of Frank Zappa.)

In The Court Of The Crimson King (1969)

I'm often amused by people who look down on so-called neo-progressive music (such as Pendragon, IQ, etc.). Why? Because so much of King Crimson's first album -- considered by many to be a groundbreaking progressive-rock work -- would today fall into the neo-progressive category. Sure, "21st Century Schizoid Man" is a savage number that opens the album with distorted guitars, tortured vocals, and uncanny virtuosity, but songs like "I Talk To The Wind" and "Epitaph," not to mention parts of the tracks "Moonchild" and "The Court Of The Crimson King," feature lovely melodies and simpler song structures, two of the characteristics of neo-prog. Of course, back in 1969, no one had ever heard anything quite like these songs or anything quite like the mellotron that drenches much of this album - thus was born progressive rock.

Although the final two tracks, "Moonchild" and "In the Court of the Crimson King," have their melodious moments, they are, at times, every bit as experimental as "21st Century Schizoid Man." In the case of "Moonchild," the centerpieces of the song are the ambient, almost avant-garde, subtracks "The Dream" and "The Illusion," which feature eerie guitar and vibes noodling, backed by inventive percussion. "In The Court Of The Crimson King", too, has its artsy moments, especially when, near the end, the song's main, regal theme collapses into a complex stew of creative dissonance.

Of historical interest is the fact that Greg Lake, who would go on to be the vocalist and bassist for Emerson, Lake & Palmer, handles the vocal duties on this album. Lake does not, however, play bass.

In The Wake Of Poseidon (1970)

This album, which still features Greg Lake on vocals, is a continuation of what Crimson was doing with In The Court Of The Crimson King. That fact notwithstanding, Poseidon is still, I think, a step forward as far as composition goes. The first track (not counting the very short "Peace - A Beginning," which, along with "Peace - An End," acts as a one of a pair of bookends for the rest of the album), titled "Pictures Of A City," opens the album in a strongly progressive vein, providing the same function as "21st Century Schizoid Man" did on the first album. Although a jazzier, less harsh, piece than its cousin, "Pictures Of A City" does feature the same lightning fast, unison stop-and-go phrases that were the trademark of "Schizoid Man," and so acts as a stylistic tie to the first album. The second and third full-length tracks, "Cadence and Cascade" and "In The Wake Of Poseidon," too, link to the first album, filling the roles of the tracks "I Talk To The Wind" and "Epitaph."

From this point on, In The Wake Of Poseidon, heads in a different direction than the first album. The track "Cat Food," an almost humorous piece that foreshadows the type of novelty song Lake would soon be singing with EL&P, is nothing like Court's "Moonchild." And, the last full-length track, "The Devil's Triangle," marks Crimson's first step into the dark, nightmarish themes that most people now associate with the group. This Bolero-like, mellotron-based masterpiece is not a track you want to listen to alone in the dark. The grim themes here build to such an intensity that they are guaranteed to generate goose bumps and make the little hairs on the back of your neck stand up. You have been warned! The return of the gentle theme started in "Peace - A Beginning" -- now titled "Peace - An End" -- helps to calm nerves shattered by "The Devil's Triangle." This would be the last time Greg Lake's voice graced a King Crimson composition.

Lizard (1970)

The third and fourth albums in King Crimson's oeuvre are perhaps the most controversial. People either love them or hate them. I think that Lizard, at least, is a masterpiece, far superior to KC's first two releases. In the case of Lizard, although the basic sound Crimson developed in their first two albums remains intact, compositions become more artsy. Gone, for the most part, are the pleasant melodies rendered in songs like "Epitaph" and "Cadence and Cascade," replaced with much darker themes and more complex and often dissonant instrumentation. (The shortest track on the album, "Lady Of The Dancing Water," which is less than three minutes long, is one of the few melodious moments on this album.) Gone, also, is Greg Lake -- who left to form Emerson, Lake and Palmer -- with the vocal chores now taken on by Gordon Haskell, who also plays bass.

While the first four songs on this album have great moments (especially the spooky "Cirkus" and the complex "Indoor Games"), the album's highlight is the lengthy title track, "Lizard," which clocks in at over 23 minutes and features, in the "Prince Rupert Awakes" subtrack, Jon Anderson from Yes on vocals. ("Prince Rupert Awakes" is the only other melodious song on the album.) Interestingly, in spite of Lizard's overall dark focus, the chorus for "Prince Rupert Awakes" is (perhaps not coincidentally, considering Anderson's presence) upbeat and reminiscent of Yes's approach to prog rock. For the most part, the rest of "Lizard" takes on a jazzy avant-garde feel, with occasional returns to the melodious Prince Rupert themes, as well as a trip back to the dark, mellotron drenched sound achieved in In The Wake Of Poseidon's "The Devil's Triangle."

Islands (1971)

One word that might describe King Crimson's fourth album, Islands, is stark. In general, much of this album is minimalist in nature. Where the previous album, Lizard, started off with the dark and almost vicious "Cirkus," Islands begins with the laid-back, slightly avant-garde "Formentera Lady," a track featuring ghostly vocals, minimal percussion, and violin accents. The ghostly vocals, however, soon give way to "Sailor's Tale," a track that even people who dislike the Islands album tend to like a lot. With its jazzy drumming, layered guitar and mellotron lines, and driving bass (in the latter half of the song, anyway), "Sailor's Tale" is a foreshadowing of what Crimson would be doing on its next album, Larks' Tongues In Aspic, and is, without a doubt, the best track on the album, and maybe even one of the best tracks Crimson has ever done.

Track 3, "The Letters," returns the album to its stark nature. A brief tale of infidelity, lines such as "Impaled on nails of ice," sung with heartfelt agony, are sure to generate goose bumps. "Ladies Of The Road," on the other hand, is a crude, simplistic, almost humorous track, whose tone (in spite of the downright Beatle-ish chorus) matches what must be the band's disdain (or maybe reverence?) for groupies. This track is as close to actual rock-and-roll that Crimson will ever get. Finally, the fully orchestrated, classical piece, "Prelude: Song Of The Gulls," is something entirely new for KC, whereas the closing track, "Islands," is moody, quiet, and pensive, featuring a gentle vocal over piano accompaniment, garnished with soft horn and flute solos.

Lark's Tongues In Aspic (1973)

It was on this album, I think, that King Crimson managed to pull together the instrumental prowess and melodic nature of the album In The Wake Of Poseidon with the artiness of the album Lizard to produce a work that all KC fans could adore. My favorite KC album, tracks here include the roaring "Larks' Tongues In Aspic, Part One" and "Larks' Tongues In Aspic, Part Two," as well as the mystical, albeit energetic, "The Talking Drum." The melodious side of KC appears as well, on the tracks "Book Of Saturday" and "Exiles," with vocals and bass this time around handled by newcomer John Wetton, the fourth KC singer in five albums. Other new additions to the band include Bill Bruford (fresh from Yes) on drums, David Cross on violin, and Jamie Muir on percussion.

Although most of this album is instrumental, John Wetton's vocals on "Book of Saturday," "Exiles," and "Easy Money" introduced the world to a great new prog voice. (He left KC long ago, but Wetton is still active in the prog scene, having turned out several solo albums.) The song "Exiles" is much like what Greg Lake was singing on the first album, In The Court Of The Crimson King, although Wetton has a coarser voice (in a good way) that you wouldn't likely confuse with Lake. With the song "Easy Money," King Crimson came close to producing (if you could remove the instrumental center part, which I, of course, wouldn't dream of doing) the kind of FM-radio prog that Pink Floyd produced with tracks like "Have A Cigar" and "Money." The sometimes moody, sometimes metalish, sometimes avant-garde, but always complex, two-part epic (over 20 minutes) "Larks Tongues' In Aspic" is among the Crim's best compositions.

Starless And Bible Black (1973)

Starless And Bible Black fits well along side Larks' Tongues In Aspic, having generally the same sort of sound and compositions. I don't think it's as successful as Larks' Tongues, however, although it's miles above most of the music that was coming out in 1974 (or since, for that matter). This time around, Crimson went from a five-piece to a four-piece, losing the percussion antics of Jamie Muir, though Bruford takes on the extra chores just fine. Like Larks' Tongues, most of this album is instrumental, although the "The Great Deceiver" -- a cranking KC tune if there ever was one -- features John Wetton on vocals, as does "Lament," a song that starts off on the gentle side of KC, but then goes through several meter changes. "The Night Watch," too, is a vocal outing, featuring a gentle melody sung over instrumentation that boasts bells, bass-guitar harmonics, mellotron, and guitar.

The rest of the album comprises dark instrumentals that seem structured one moment and improvisational the next. The disarming and atmospheric "Trio" leads into the spooky mellotron of "The Mincer," which itself evolves into a collage of guitar played over Bruford's and Wetton's tasty rhythm section. Wetton also has a short vocal section in this track, although it's more of a melodic chant than anything like a verse or chorus. The title track, "Starless And Bible Black," starts off on the avant-garde side and sounds mostly improvisational, building as it goes into a cacophony of percussion, snarling bass, and Fripp's trademark guitar wail. Finally, "Fracture" is a cousin to the previous album's title song, "Larks' Tongues In Aspic," though it's more musically subtle, spending much of its 11 minutes on the quiet side. Things don't really kick into high gear until almost eight minutes into the track, when the boys finally work up a serious sweat.

Red (1974)

With the album Red, KC returned as a power trio, with Wetton and Bruford joining Fripp for a powerhouse set of metalish instrumentals and vocal pieces. This would be the last album that featured the dark sound that KC had been cultivating since "20th Century Schizoid Man" and that peaked with the album Larks' Tongues In Aspic. (After Red, King Crimson would go on hiatus and not return until the 80s, with a brand-new sound that would rely heavily on the extraordinary guitar and vocals of Adrian Belew.) Red's intensity is the sound that newer KC-inspired bands such as Anekdoten borrow from today and is also a favorite among KC fans.

The title song "Red" -- a concert staple for King Crimson -- is a strong instrumental that features reams of distorted guitar, snarling bass, and pounding drums. On "Fallen Angel," the pace at first slows a bit, enabling Wetton to demonstrate his vocal prowess on the song's gentler melodies, but the metal edge soon returns in the track and continues on through the second vocal track, "One More Red Nightmare." Next, the instrumental "Providence," like the closing tracks on the previous album Starless And Bible Black, seems mostly improvisational, but no less nightmarish. The final track, "Starless," at first harkens back to the gentler, mellotron-saturated songs such as "Epitaph," but the nightmare returns about five minutes into this 12-minute piece. Perhaps most curious about this final track is that, with the repeated lyric "Starless And Bible Black," it seems as if this song was originally meant as the title song for the previous album.

King Crimson

In the Court of the Crimson King

An Observation of King Crimson's First Album

Band Members: Robert Fripp (guitar), Greg Lake (bass and lead vocals), Ian McDonald (flutes and keyboards), Michael Giles (drums and percussion), Peter Sinfield (lyrics and lightshows).

Producer: King Crimson.

Engineer: Robin Thompson & Tony Page (assistant).

Tracks: 1. 21st Century Schizoid Man, including Mirrors (7:20), 2. I Talk To The Wind (6:05), 3. Epitaph, including March For No Reason & Tomorrow And Tomorrow (8:47), 4. Moonchild, including The Dream & The Illusion (12:11), 5. The Court Of The Crimson King, including The Return Of The Fire Witch & The Dance Of The Puppets (9:22).

The musical scene in the late sixties

The year was 1969. Progressive rock has not been invented yet. but some early attempts had been made, mostly inspired by psychedelic hippie vibes. The Beach Boys had already started exploring the possibilities of multi-tracking ("Pet Sounds", 1966), Jimmy Hendrix started combining R&B with psychedelic rock ("Are You Experienced" 1967), and the first so called "concept albums" were released, like "St. Peppers" by the Beatles and "Days Of Future Past" by the Moody Blues.

Procol Harum had already recorded their organ classic "A Whiter Shade of Pale", but the track wasn't included on their debut album "Procol Harum" (1967). Classical influences were also present on the first two albums by The Nice (with Keith Emerson). And in this period, three young dinosaurs were born, Pink Floyd, Genesis and Yes, but their first albums still were rather "flower power" than what we now call progressive rock.

Then suddenly, an album was released by a new band, King Crimson. It came in a strange and frightening cover, that seemed to fit the music quite well. The music was something completely new and overwhelming, both fragile, majestic and aggressive, with unusual sounds, changing time signatures, and complex arrangements.

For many people, this album "In The Court Of The Crimson King, An Observation by King Crimson" marked the true start of progressive rock. For this reason, this article will try to give some background information on how this album came together.

The formation of King Crimson

The idea for King Crimson was conceived in London 1968. Michael Giles (drums) and his brother Peter Giles (bass) had been playing in several bands all over the country. In London they met guitarist Robert Fripp, who had been there since 1967, without work, but with the desire to become a professional musician. As he recalls: "I arrived in London with Sergeant Pepper's bubbling inside of me. Hendrix, Bartok string quartets, an experience of passionate music".

Fripp and the Giles brothers formed a band (Giles, Giles & Fripp) and in 1968 recorded an album "The Cheerful Insanity of Giles, Giles and Fripp". The album was described as a combination of the silly Beatles stuff, Monty Python and the Moody Blues in their less pompous moods. Unfortunately, the album was quite unsuccessful and GG&F failed to get any gigs.

During November 1968, the idea for a new band was formed, without Peter Giles, but with two other members from the GG&F-team: lyricist Peter Sinfield and multi-instrumentalist Ian MacDonald. Sinfield came up with the new band's name: King Crimson, "a synonym for Beelzebub". Fripp also contacted an old friend, Greg Lake, who had just left his band The Gods, and was trying to get a solo record deal. Lake agrees to join them and moves to London.

Crimson rehearsals and performing

King Crimson started rehearsing in January 1969 in a cafe basement, usually in the presence of a small audience of friends. Most of the music evolved from these rehearsals, with all of the members bringing in ideas and suggestions.

"We didn't really have a formula", Lake remembers, "All we knew was that the music had a life of it's own". The same idea was expressed by the other band members (Giles: "The music was playing us" and Fripp: "the music came to live, of itself, as we played it").

Lake felt that as musicians they were totally unconnected. According to Fripp, the main things that kept the band together were commitment and creative frustration. They felt that, after years of doing things which were unsatisfying, they should create an opportunity to do what they wanted.

In Giles' words: "We wanted to make music that didn't sound like anybody else's music. Our intention was to make some powerful, adventurous new music that hadn't been done before, and make our mark on the world".

Of course, 1969 was the time of the student demonstrations in Paris, Vietnam, flower power, drugs and the hippie movement. But according to Giles: "We were somehow outside that, just concentrating on the music. There was a lot of concerts and club dates, and the audience just sat and listened, they had a longer attention span. I can remember bands like Soft Machine, which was far more complicated music".

Picture of the early Crimson

From April 1969 the band started its first official gigs, starting as an opening act for other bands. But they soon crashed the main programme, because of their powerful performance. Their sound was quite "new"; they were loud, using unusual sounds like the mellotron and electrified saxes. Also adding to the musical magic was Sinfield's light show. As Sinfield recalls: "I would go: blue, blue, rrrrr ed , b b b blue- and Ian or someone would respond to the colour sequence with a musical phrase. It was a very wonderful feeling!"

The Album

In June 1969, the band started the recording of their first album. The album came in a remarkable sleeve by Barry Godber. Fripp: "The face on the outside is the Schizoid Man, and on the inside it's the Crimson King. What can one add? It reflects the music". This cover was the only one Godber ever did, as he died in 1970 at the age of 24.

The album was originally to be produced by Tony Clark (who also worked with the Moody Blues), but eventually the band decided to produce the album themselves. The recording and mixing took about 10 days. It's important to notice here that Fripp has always regarded King Crimson as a live band, and not a recording unit. For him, a recording can only capture a part of the music that is happening. Still, the album can be seen as an important musical milestone. The album was finished in August and officially released in October. On the album were only 5 long pieces:

1. 21st Century Schizoid Man

(incl. Mirrors)

"Cat's foot, iron claw

Neuro-surgeons scream for more

At paranoia's poison door

Twenty first century schizoid man"

The albums starts with the frightening "21st Century Schizoid Man", which Fripp once referred to as "the first heavy metal track". This piece demonstrates the energy and aggression of the musicians: Lake's metallic distorted vocals, McDonald's electrically amplified saxophones, Giles' restless jazzy drumming, the uncompromisingly fast instrumental middle section and Fripp's wild guitars. The song was basically written by Lake, but in fact is a group effort, evolving from rehearsals. This song must have been quite a shock for the listeners in those days, as it was unlike any of the music they had heard before.

2. I Talk to the Wind

"I talk to the wind

My words are all carried away

I talk to the wind

The wind does not hear

The wind cannot hear"

After the powerful opening, follows "I Talk to the Wind", a peaceful and dreamy piece, mainly carried by the beautiful flutes of MacDonald, who wrote the song. Macdonald:

"It was a very simple folky song, but done in a context that one might call progressive". The track also appeared on the GG&F-album, and there is also an early version, sung by Judy Dyble, formerly of Fairport Convention.

3. Epitaph

(incl. March For No Reason & Tomorrow And Tomorrow)

"Confusion will be my epitaph

As I crawl a cracked and broken path

If we make it we can all sit back and laugh

But I fear tomorrow I'll be crying"

This piece was another band effort, based on Sinfield lyrics, with Lake's song part added, and all members contributing musical ideas. The music is heavy, not because it's loud, but because of it's dramatic melody, its minor key, and the classic sound of the mellotron. A short snippet of this song can also be heard on ELP's 1974 live album ("Welcome Back My Friends").

"Epitaph" is also the name of a collection of live recordings, released in 1997, which give a nice impression of the live performances of the first Crimson line up in 1969, with more improvisations, and some material that had previously been unavailable.

4. Moonchild

(incl. The Dream & The Illusion)

"She's a moonchild

Gathering the flowers in a garden

Lovely moonchild

Drifting on the echoes of the hours"

Side 2 of the LP (remember?) starts with "Moonchild", a piece in two parts. The first part is a romantic hippie ballad, for which Sinfield wrote the lyrics after he had fallen in love with his new wife, Stephanie. After the "song part" starts an long instrumental section, spontaneously recorded without Greg Lake. It's a free improvisation, with no melody and almost inaudible. For many people (some band members included) this section didn't really work on the album, but it's interesting to see why it was included. Sinfield:

"We were a bit short of material for the album, and we decided to do something that represented the often most amusing/entertaining/perverse part of our live show".

5. In The Court Of The Crimson King

(incl. The Return Of The Fire Witch & The Dance Of The Puppets)

"The purple piper plays his tune

The choir softly sing

Three lullabies in an ancient tongue

For the court of the Crimson King"

The album closes with the title track, the majestic mellotron piece "In The Court Of The Crimson King". The story of the Crimson King was inspired by several historical figures, most notably the Emperor Frederick II (1194-1250), a rebellious despot. Originally, this was a tune all written by Sinfield for his earlier band 'Creation'. The song was completely rewritten for King Crimson, with a melody line by Lake.

Response to the album

When it came out, the album was very well received. There seemed to be an audience for music that was not primarily entertaining, but more serious and intellectual in both lyrical and musical terms. In this perspective, the album is very close to "Days of Future Passed" by the Moody Blues.

Even more than the Moodies, King Crimson's "Court" laid down an important foundation for a new musical style that became known as "progressive rock" (although the band members were never too keen on the word).

The band's "epic" approach of the song material, and the complex arrangements became very influential to a new generation of musicians, thus marking a point were pop musicians wanted to be more than "just" pop, trying to give popular music a more serious treatment, and maybe even create some new form of Art.

End of the original line up

After King Crimson's USA tour in December 1969, the original band fell apart, as MacDonald and Giles decided to leave. Several reasons were given: the sudden success of the band, the pressure of touring, and the fact that the members didn't communicate too well. Giles had fallen in love and wanted to spend more time at home, and MacDonald wanted to make more personal and happier music, "with less paranoia, aggression and frustration".

Soon after, a problem arose between Lake and Fripp, both two strong characters. Fripp had some very clear ideas about the band's musical course, and wanted full control. Lake recalls: "Bob wanted to work to a situation where he was in the driving seat over the other musicians involved, which I can dig, but not for me." Lake also felt a bit underrated in the band, and wanted more credit for his songwriting. All this finally resulted in the departure of Lake.

In 1970, a "new" King Crimson started recording their second album, "In The Wake Of Poseidon". This was a messy period, in which Fripp was still trying to get his new band together. The line up on "Poseidon" was a strange mixture of both old and new band members. The official new singer was Gordon Haskell (who only sang on one track), but most of the album was sung by Lake. Also new were Keith Tippeth (piano) and Mel Collins (flutes and saxes). Mike Giles temporarily returned to play the drums, and his brother Peter Giles (from GG&F) played bass.

There are several interesting stories about this period, like Yes asking Fripp to replace their guitar player Peter Banks (which he refused), and Elton John being asked to do some work as a session singer for "Poseidon" (cancelled by Fripp).

"Whatever became of..."

So what happened with the members of the original King Crimson line up? To conclude this article, just some short notes...

Greg Lake became very successful as part of the trio Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Fripp did express his interest in working with ELP (as did Jimmy Hendrix), although this never happened, probably because Emerson wasn't too interested in working with another guitar player. ELP released their first album in 1970, and beside his work with ELP, Lake also recorded some solo albums, sometimes collaborating with Gary Moore.

MacDonald and Giles recorded a new album in 1970 (McDonald & Giles). However, this was just a studio thing, never intended to become a band. After that, Giles became a session musician, working with Rupert Hine, John Perry and Ant Phillips, and also doing some film and television music.

MacDonald moved to New York, where he started working with the very successful band Foreigner (debut album 1977). He incidentally played with King Crimson and did some production work. More recently, MacDonald made a solo album, "Drivers Eyes" and played with Steve Hackett and John Wetton.

The collaboration between Fripp and Sinfield came to an end in December 1971. He kept writing lyrics, working for ELP and the Italian band PFM. He also recorded a solo album in 1973, "Still" (re-released as "Stillusion"). More recently, Sinfield started to write lyrics for more poppy bands, like Bucks Fizz's "The Land of Make Believe" (which he described as an "anti-Thatcher song").

And Robert Fripp, finally, of course kept working with King Crimson. Through the years, the band went through several personal and musical changes. In the seventies Crimson recorded albums like "Lizard" (1970), "Islands" (1971), "Lark's Tongues In Aspic" (1973), "Starless And Bible Black" (1974) and "Red" (1974). In 1981 a new Crimson arose, and the band is still active in 2002, with several side projects.

Fripp has also recorded some solo albums, worked with Peter Gabriel, Brian Eno, David Sylvian, Andy Summers and many others. He also gives workshops for guitarist, and often surprises the world with his cynical, humorous statements:

"We're not to be enjoyed. We're an intellectual band!"

Written by Rob Michel (April 2002).

For this article I made use of several sources, like the album booklets to KC's "Young Person's Guide" and "Epitaph", Eric Tamm's book "Robert Fripp, From King Crimson to Guitar Craft", and various interviews found on the internet. Recommended website for further reading: www.elephant-talk.com

King Crimson - In the Court of the Crimson King

Member: TopographicYes

This is arguably the first 'progressive rock' album, even though King Crimson's In The Court Of The Crimson King came along before the term progressive rock even existed. At the time it was considered psychedelic music. Whatever you may wish to call it, one thing is certain, it's excellent- an incredibly strong piece of work from a debut band. They had a vision and it emerged fully formed, sending a shock wave through the music community at the time. "An uncanny masterpiece", declared Pete Townshend. Jimi Hendrix called Crimson, "the finest band ever". Maybe The Beatles were amazed as well...

The "They" in question where Robert Fripp on guitar, Greg Lake on bass and lead vocals, Ian McDonald on reeds, woodwinds, vibes, keyboards, mellotron and vocals, Michael Giles on drums and vocals. Crimson emerged out of the ashes of the Giles, Giles and Fripp group in mid 1968. The only difference lineup wise is that Lake replaced bassist Peter Giles. Peter Sinfield penned the lyrics for this album and is almost the extra band member in a sense. His lyrics were integral to the sound of the original Crimson.

From a musical standpoint this was a new sound that took it's audience by surprise. Apart from the bombastic "21st Century Schizoid Man", ITCOTCK has a grand, symphonic sound. The lush mix of instrumentation (winds, mellotron, etc.) gave Crimson a sound that was bigger than any 'rock' band. They took the symphonic sound of the Moody Blues and injected it with a dose of sinister realism. Live they gave their audiences no quarter. Word spread fast.

"Schizoid Man" opens the LP with a bang. What may sound a little tame now must have been downright scary to listeners when it came out. Crimson has always been known for muscular numbers, ones that require pristine chops to execute. This is where it all started, the template for Crimson's heaviness is "Schizoid Man". This song has more in common with the dissonant workouts of Larks era Crimson than anything else on ITCOTCK. Fripp's alternate picking is highly evolved for 1969. No wonder many considered him the finest guitarist of the time. Most of his contemporaries were picking their jaws off the floor when they heard this tune.

The rest of the LP is very symphonic, a sound that would continue through the next 3 Crimson albums. ITCOTCK is about creating a mood more than hitting the listener over the head with chops. Greg Lake turns in some of the best vocals of his career on ITCOTCK. He's downright angelic sounding, a choirboy fronting a monster.

"I Talk To The Wind" is an old Giles, Giles and Fripp song. Here it's redone by Crimson. There is a strong Beatle infulence here. Given the time, it's no shock. Some say the original version of this song is better. What do you think? I think it's a real beaut.

"Epitaph" is a mellotron drenched minor key feast for the ears. A strong expression of longing is shared with the listener. Lake sounds as if he's on the edge of something very deep.

"Moonchild" is another mid tempo, minor key tune, one that doesn't reach it's full potential. After the first 3 minutes or so it just meanders on and on. Not my fave track on this LP.

"In The Court Of The Crimson King" is another Mellotron driven number. As grandiose as the name implies, ITCOTCK has a bit of everything that came earlier on this album.

Overall this album starts out very aggressive and then settles into a mid tempo vibe that is more ethereal. Personally, I think the bands second album is a more rounded affair. One thing that's absent here is the bands sense of humor, this is a very serious album. Bold, somber and fit for royalty. If you are interested in the roots of prog rock start here and work your way forward, it will be quite an amazing journey.