|

|

|

01 |

Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Part One |

|

|

|

13:35 |

|

|

02 |

Book Of Saturday |

|

|

|

02:55 |

|

|

03 |

Exiles |

|

|

|

07:40 |

|

|

04 |

Easy Money |

|

|

|

07:53 |

|

|

05 |

The Talking Drum |

|

|

|

07:25 |

|

|

06 |

Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Part Two |

|

|

|

07:07 |

|

|

|

| Country |

United Kingdom |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

David Cross: Violin, Viola, Mellotron

Robert Fripp: Guitar, Mellotron & Devices

John Wetton: Bass & Vocals

Bill Bruford: Drums

Jaime Muir: Percussion & Allsorts

Bob Eichler:

Of the three mid-70s Crimson albums, this is probably my least favorite, but that's kind of like saying my pinky is my least favorite finger - I sure as hell wouldn't want to be without it. I think my problem with this album is that there are live versions of just about every track from it that I prefer to the studio versions. But that's just an indication of the skill that this version of Crimson had on stage - there really aren't any bad tracks on this disc (although I could probably live without "Easy Money", and I have to be in the mood for "Exiles"). This may be an unpopular opinion, but I prefer the version of "Lark's Tongues, pt 1" on the Frame by Frame boxed set, where Fripp wisely edited out a bit of noodling and made it a tighter track.

Dominique Leone:

What do you think of when you hear the term 'progressive rock'? If you were like most people, then you might have conjured visions of bloated, obsolete 70s bands whose members wear robes onstage, and whose album covers have more in common with Hobbits than heartbreakers. With this album, KC seemingly tried to change all that. Here, they replace prog mysticism with cynicism, pompous rock-suites with compact avant tone-poems, and the whole stigma associated with art rock with something much more subversive.

The sound is cutting and dark. Percussionist Muir helps a lot by banging on just about anything except actual drums. Chalk up the album's medieval whimsy to his nimble hands and feet. David Cross, though soon to be maligned by his bandmates, gives the whole proceeding an air of real classical experimentation. Wetton and Bruford were KC's best rhythm section, due much in part to the clashing of their styles: Wetton's brash, distorted punch versus Bruford's no-nonsense refinery. Fripp assembled a band that could push the envelope, and jam with the best of them.

The first track on the album, "Larks' Tongues...Pt. 1", established a creed for this band to follow until its dissolution in '74. Exotic percussion, building tension, guitar explosions, extended group improvisation, the spooky tritone dissonances: it's all here. We're still in the 12-minute range, but this feels more like the soundtrack to a ghost story than escapist pomp.

"Larks' Tongues...Pt. 2" is all roaring riffage from RF and company. Whatever retraint they showed on the album up to now was blasted out of the water on this tune. Angular divebomb madness, with plenty of sweat to back up its pretensions. The band would go on to make two more "Larks" sequels over the next 25 or so years, neither of which matched the intensity or imagination of the first two.

As you may know, this was KC's first album with the classic mid-70s lineup. The really scary thing about it is that it arguably wasn't even that band's best album! Breathless, before RF thought up that title.

Sean McFee:

This is the first album recorded by the incarnation of King Crimson involving Fripp, Bruford, Wetton and Cross. Legendary percussionist Jamie Muir also lends a hand on this album.

Larks' Tongues in Aspic is one of the staple progressive rock recordings. I would imagine three quarters of the people reading this review have already heard the album. Nevertheless I'll attempt to give some thoughts on it.

The album opens with some atmospheric, meandering percussion which gradually builds into the first number, "Larks' Tongues in Aspic Part 1", which alternates between softer passages controlled by violin and the harsh guitar riffs of Robert Fripp. As this manic-depressive slugfest drifts away, the listener is led through the wistful balladry of "Book of Saturday" and "Exiles" and the rockier "Easy Money". The minimalist and hypnotic "Talking Drum" leads into the harsh guitar epithets of "Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Part Two".

This is probably the least heavy of the mid-period Crimson albums, but offers a mix of styles, in all of which the band is greatly proficient. In terms of accessibility, this is easier to get into than Starless and Bible Black and harder than Red. It's really difficult to pick a winner between the three, as all are classic fare that belong in your collection. Recommended.

Joe McGlinchey:

After the lackluster Islands, Robert Fripp emerged with a new Crimson line-up in 1973, and the music that was to follow over the next two years, both in the studio and especially live, is usually considered to be the apex of the band's legacy. The quintet that recorded Larks' Tongues in Aspic (their fifth studio album), though short-lived, was a wonder to behold. The "pros" Bill Bruford and John Wetton provided the band with a solid, virtuosic rhythm section, while the "newbies" David Cross and Jamie Muir (Muir soon departed after this album) beautifully countered, giving the band a newfound sense of liberation and spontaneity. And, of course, there was Fripp himself, the fulcrum of the see-saw. Every song on this recording is a winner, from the aching, bittersweet symph-prog of "Exiles" (a strong candidate for my favorite Crimson song) to the hair-raising intensity and perfect execution of "Larks' Tongues in Aspic, part two." A classic of the genre.

Eric Porter:

King Crimson can be very difficult to listen to and appreciate. This one was difficult for me at first. "LTIA Part One" is very experimental, heavy in spots with lots of violin, and tempo and dynamic shifts, along with KC_s noise thrown in. "Book of Saturday" is a guitar vocal piece, not really one of my favorites. "Exiles" features some excellent violin from Cross; a relatively mellow piece. "Easy Money" also has alot of improv, extended guitar soloing, sound effects and some mellotron as well. "Talking Drum" has lots of percussion, bass kicks in and band plays off the rythym, continues to build and build. "LTIA Part Two" shows the direction they were heading into with Red, as this is heavy and flat out rocks. This one is worth the price of admission on its own. I go through stages with this, sometimes I love it, and sometimes I find it hard to listen to.

Brandon Wu:

King Crimson is perhaps the most respectable of the classic 1970s progressive rock bands, and this is, in my opinion, their most respectable release. Three "songs" in the more conventional sense are sandwiched between three complex, instrumental, comparatively avant-garde works. The opening track has it all: amazing percussive runs, fast guitar picking, headstrong bass playing, and violin playing both evil and soulful. In its 13 minutes, this title track meshes hard rock and classically-styled ensemble playing into an uncategorizable masterpiece. This, perhaps King Crimson's most avant-garde composition, then gives way to a couple of soulful, lyrical songs, of which "Exiles" is perhaps the single best "song" that the band has ever done, with beautifully melodic - and memorable - violin playing rising out of a restless, noisy Mellotron introduction. While the song "Easy Money" may meander a bit in its middle section, the band turned this into an effective vehicle for improvisation live, so that can be excused. Finally, the percussive tour-de-force "The Talking Drum" may be criticized as being nothing but an overly lengthy buildup, but as such it is amazingly effective as it leads into the screamingly loud "Larks' Tongues part 2", whose odd-metered heavy guitar riffing must have influenced the heavy metal bands which evolved years later. A diverse and electric album, and one of those few rock releases which still sounds completely fresh and modern more than 25 years after its recording. Perhaps I'm biased - this is one of my favorite albums ever, and IMHO the best of King Crimson's repertoire - but most would agree that every prog fan has to hear this one eventually, no matter what.

Larks' Tongues in Aspic

Date of Release 1973

King Crimson reborn yet again - the newly configured band makes its debut with a violin (courtesy of David Cross) sharing center stage with Robert Fripp's guitars and his Mellotron, which is pushed into the background. The music is the most experimental of Fripp's career up to this time - though some of it actually dated (in embryonic form) back to the tail end of the Boz Burrell-Ian Wallace-Mel Collins lineup. And John Wetton was the group's strongest singer/bassist since Greg Lake's departure three years earlier. What's more, this lineup quickly established itself as a powerful performing unit working in a more purely experimental, less jazz-oriented vein than its immediate predecessor. "Outer Limits music" was how one reviewer referred to it, mixing Cross' demonic fiddling with shrieking electronics, Bill Bruford's astounding dexterity at the drum kit, Jamie Muir's melodic and usually understated percussion, Wetton's thundering (yet melodic) bass, and Fripp's guitar, which generated sounds ranging from traditional classical and soft pop-jazz licks to hair-curling electric flourishes. The remastered edition, which appeared in the summer of 2000 in Europe and slightly later in America, features beautifully remastered sound - among other advantages, it moves the finger cymbals opening the first section of the title track into sharp focus, with minimal hiss or noise to obscure them, exposes the multiple percussion instruments used on the opening of "Easy Money," and gives far more clarity to "The Talking Drum." This version is superior to any prior CD release of Larks' Tongues in Aspic, and contains a booklet reprinting period press clippings, session information, and production background on the album. - Bruce Eder

King Crimson

Larks' Tongues in Aspic

1973

EG

In 1969 King Crimson released what many consider the first full-fledged progressive rock album: In the Court of the Crimson King. This album won the band instant acclaim and was vastly influential in shaping the sound and style of the burgeoning progressive rock movement of the early '70s. By 1971, Crimson had released three other studio albums that all fell more or less in line with the popular symphonic rock style it had helped to create with In the Court of the Crimson King (Lizard being a possible exception). Then King Crimson changed radically.

Rather than continue in a style which Crimson's unofficial leader Robert Fripp would eventually deem dead and bloated, Fripp shifted gears, beginning the push for the figurative and literal red line portrayed in the music and on the back cover of the band's temporary swansong, Red. This dramatic shift was made all the more possible because all the previous members of King Crimson (except Fripp) quit and were replaced with fresh, very forward thinking musicians. Bill Bruford, John Wetton, Jamie Muir and David Cross were all recruited to join the ranks of the Crimson King in 1972. By early 1973 the band had released an album that was every bit as groundbreaking and eye-opening as In the Court of the Crimson King had been. Larks' Tongues in Aspic shattered all previous notions of what progressive rock or King Crimson should sound like. In fact, in the liner notes to the Epitaph box set Fripp has even denied that King Crimson's music post-1970 even qualifies as progressive rock. While these attempts to disassociate from the progressive movement (also practiced by members of other seminal progressive bands in recent years) may irritate prog fans, Fripp's argument has some merit by the time of Larks' Tongues in Aspic. None of the big name prog bands had ventured into such unpredictable territory and none would dare to follow. The large-scale commercial success they achieved in the mid-'70s would have been impossible if they had.

Larks' Tongues in Aspic is a remarkable album for several reasons. Firstly, it deviated from what would become prog rock's traditional mold while the mold was still relatively new. Many of the elements of classical music that had become hallmarks of King Crimson and prog rock in general were abandoned with Larks' Tongues in Aspic. Instead, the group looked increasingly toward jazz and the avant-garde for inspiration. The 1972-74 incarnation of King Crimson would become known for its stunning prowess in the area of improvisation. This was not improvisation in the manner of most rock groups of the day, which usually meant a guitarist improvising a solo over a repeated chord progression. This was real group improvisation in which almost everything played by each member was unscripted. There is only a little improvisation on Larks' Tongues in Aspic, (there would be much more on the next two albums) but the band had begun experimenting with serious improvisation before the recording of Larks' Tongues in Aspic, and evidence of the newfound freedom it provided is certainly apparent in the compositions on the album.

Larks' Tongues in Aspic is also unique for its subtle incorporation of non-western musical influences for the first time on any King Crimson album. On page 59 of the libretto to The Great Deceiver box set, David Cross writes about early auditions for forming the Larks' Tongues in Aspic band: "We had a jam with a wonderful eccentric gentleman/musician called Jamie Muir with a view to doing an Indian type album." Cross goes on to point out that the Indian album never happened, but there is no question that experimentation with non-Western musical traditions made an impact on the sound of Larks' Tongues in Aspic. The use of thumb piano (from Africa) and dulcimer (an ancient instrument possibly originating in the Middle East) on the first track are clues, but more so are the unusual scales and melodies found throughout much of the album. "The Talking Drum" and "Larks' Tongues in Aspic" parts one and two all nod to exotic scales and Oriental sounding melodies. While the incorporation of non-Western influences into rock music had already begun well before 1972, King Crimson was on the front line of bands doing it in a more profound way. King Crimson's approach on Larks' Tongues in Aspic was in stark contrast to the more common technique of adding a token sitar player in the background for a song or two.

One final trait that makes Larks' Tongues in Aspic so unusual is its amazing dynamic range. Drastic contrasts between loud and soft were always a hallmark of early King Crimson music, but Larks' Tongues in Aspic took this phenomenon to a much higher level. In Eric Tamm's book, Robert Fripp from King Crimson to Guitar Craft, the writer illustrates this point perfectly.

"Dynamic contrast is of the essence in the music of Larks' Tongues. There is a psychological difference between loud and soft, after all, and in an age when compressors and limiters have squashed the dynamic range of recorded popular music down to the point where a delicately plucked acoustic guitar note or sensitively crooned vocal phrase comes out of your speakers at the same actual volume level as the whole damned synthesized band when it's blowing away at top intensity, listening to Larks' Tongues' startling contrasts of dynamics is a tonic for the ears. It's more real, it's more true."

King Crimson's music had always displayed an unusual deftness for contrast between moods of different songs. This has been a characteristic of much of progressive rock, but few progressive rock bands achieved such diversity on a single album as the early incarnations of King Crimson, and Larks' Tongues in Aspic is one of the most diverse King Crimson albums ever. The very fact that the simple ballad "Book of Saturdays," adorned with little more than its beautifully tender backward guitar solo, could coexist so successfully on the same album with the roaring math-rock manifesto that is "Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Part Two" is stunning. How about the dynamics between the seething, almost atonally distorted guitar riff near the beginning of the opening track and the frail, melancholy violin cadenza in the middle of it? This kind of dynamism in rock music was rare in 1972. Thirty years later it's a totally foreign concept.

Larks' Tongues in Aspic benefited greatly from the musicians who played on it. King Crimson has always included excellent musicians but Larks' Tongues in Aspic represented a leap forward in this respect. Fripp's exceptional guitar work had earned notoriety since almost day one, but Larks' Tongues marks the beginning of King Crimson's transformation from a symphonic band to a guitar band. "Larks' Tongues in Aspic Part One" unveils what would become Fripp's trademark propensity for ultra-fast, snake-like melodies. "Larks' Tongues" parts one and two also contain the heaviest chord riffs of any Crimson album up to that time. True to Fripp's multifaceted guitar personality, however, he also brings some of his most touching and beautiful solos to the table as well. Over the years, Frip's black Les Paul has burned, wailed, sawed the sky and shredded wallpaper at thirty paces, but rarely has it ever wept so gently as it does at the end of "Exiles."

Of course, Fripp's bandmates on this album were all excellent in their own ways too. John Wetton's voice is legendary among prog circles, but perhaps nowhere among all the UK, Asia and King Crimson releases on which he worked does he sing more beautifully than on "Exiles." And where else does he sound as exasperated as on "Easy Money"?

The contribution of David Cross also should not be underestimated. In the beginning of this lineup's lifetime, Cross' violin balanced out the band's increasing tendencies toward heaviness and virtuosity (the band eventually won). Cross was a classically trained player, but he was not a virtuoso by classical standards. Technically speaking, his violin playing may have seemed weak in comparison to that of someone like Jean-Luc Ponty (Mahavishnu Orchestra) or Didier Lockwood (Magma), but his presence on Larks' Tongues in Aspic provides an important organic, acoustic and often melancholy tone to the proceedings. Just listen to the very last chord he plays at the very end of "Larks' Tongues in Aspic Part Two." (You'll have to turn it up loud.) After all the seething, macho, heavy riffing - and right in the middle of the dissonance of John Wetton's bent bass strings relaxing into feedback - we have Cross' violin sweetly playing a single chord at the end of it all. It sounds so innocent and sweet, as if it represents the achievement of catharsis by the previous seven minutes of aggression. Brilliant!

Jamie Muir, (credited with percussion and "allsorts") lends rich imagination and innovation to the album. If not for him, Larks' Tongues in Aspic would have a much more sterile sound and would not be nearly the headphone album it is. This is an album that reveals things one has never heard before years after the first listen, largely due to Muir and his bag of tricks - aluminum pie pans, bowed cymbals, strange noises, etc. What a pity he did not stay with Crimson longer.

Bill Bruford, as we all know, was already an accomplished drummer with Yes when he joined King Crimson, shortly before Larks' Tongues in Aspic was recorded. His inclusion in Crimson helped him become one of the most respected and unique drummers of his generation. At this point, however, he was just beginning his transformation into a more experimental, well-rounded percussionist.

Without Larks' Tongues in Aspic, there could have been no Starless & Bible Black and no Red. Without it, later progressive bands like Present, Bi Kyo Ran, Philharmonie and Anekdoten would have sounded very different - or maybe they would not have existed at all. Thirty years after its release, Larks' Tongues in Aspic remains not only one of King Crimson's most important albums, but also one of the most imaginative and groundbreaking rock albums in history. - SH

King Crimson - Larks' Tongues in Aspic

Member: earthworksman

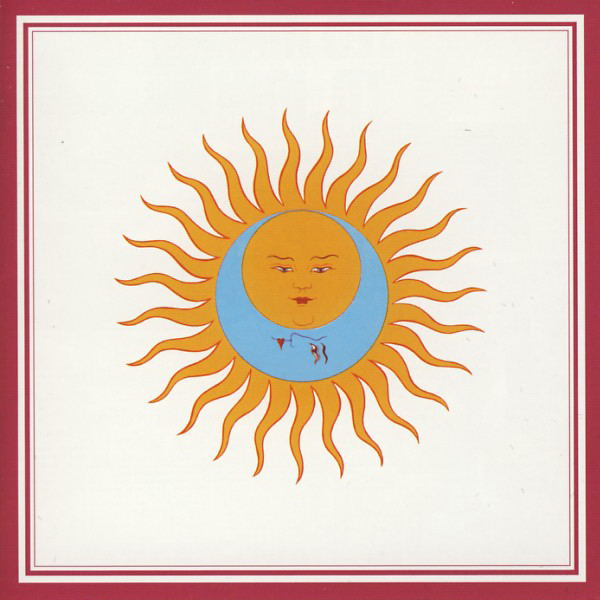

In July of 1972, Fripp announced that he was forming a new King Crimson with John Wetton, Bill Bruford, David Cross, and Jamie Muir. It was the addition of Wetton, bassist extraordinare from the respected Family & Bruford, the "jazz" drummer from the then becoming popular Yes, that made everyone take notice. Naturally, expectations were high, and King Crimson did not disappoint. From the opening, with Jamie Muir on kalimba (or thumb piano), to the closing thrashing of Bruford & Muir, Larks' Tongues In Aspic represents extremes. The cover, however, does not indicate the aural psychosis the listener will experience, unless he or she knows that it is a tantric symbol that represents both the masculine and the feminine; the yin and yang.The opening title track (part 1), in and of itself, represents these extremes. From Muir's sweet, child-like kalimba playing, to the intellectual heavy metal riff of Fripp's & Wetton's that leads to the jamming of Fripp & Wetton, to the delicacy of Cross's violin playing, LtiA Pt 1 is all over the place, thematically and dynamically. The drama can be overwhelming.The next track, "Book of Saturday", gives the listener a break. A short and quiet tune featuring Wetton on vocals, it begins with Fripp's subtle and nimble playing. The song gradually adds each of the musicians at the appropriate time and even includes some back-masked playing from Fripp. Probably, the most complex "ditty" ever recorded."Exiles" closes the A side. A gentle and poignant song, it features some of Wetton's best singing, a haunting accompaniment from Cross, a very tasteful minimalistic Bruford & Fripp on the rare acoustic. This is quite possibly the most beautiful song King Crimson has recorded."Easy Money" opens the B side. Though not fully realized, this song hints at what KC3 is like live, with a middle section that shows how the band could improvise as a unit and change the entire structure of the song.

Via a segue, we get "Talking Drum." Beginning with Jamie Muir on a talking drum, the song is very quiet, that slowly crescendos as Cross & Fripp take turns improvising over the rhythm section. By song's end, the band is at full volume and in full force ready to blast out the heaviness of the closing track."Larks' Tongues in Aspic 2" closes the album with more intellectual power chords from Fripp, Wetton's powerful yet nimble bass playing, an unnerving solo from Cross, and syncopation galore from Bruford. The song and album closes with Bruford & Muir thrashing about on percussives that leads to the final chord that hangs in the air for what seems like a short eternity (a la the Beatles' A Day in the Life) and punctuates the first true masterpiece of KC's discography.