|

|

|

01 |

Love Me Do |

|

|

|

02:23 |

|

|

02 |

Please Please Me |

|

|

|

02:03 |

|

|

03 |

From Me To You |

|

|

|

01:57 |

|

|

04 |

She Loves You |

|

|

|

02:22 |

|

|

05 |

I Want To Hold Your Hand |

|

|

|

02:26 |

|

|

06 |

All My Loving |

|

|

|

02:08 |

|

|

07 |

Can't Buy Me Love |

|

|

|

02:13 |

|

|

08 |

A Hard Day's Night |

|

|

|

02:34 |

|

|

09 |

And I Love Her |

|

|

|

02:31 |

|

|

10 |

Eight Days A Week |

|

|

|

02:45 |

|

|

11 |

I Feel Fine |

|

|

|

02:19 |

|

|

12 |

Ticket To Ride |

|

|

|

03:11 |

|

|

13 |

Yesterday |

|

|

|

02:07 |

|

|

14 |

Help! |

|

|

|

02:19 |

|

|

15 |

You've Got To Hide Your Love Away |

|

|

|

02:11 |

|

|

16 |

We Can Work It Out |

|

|

|

02:16 |

|

|

17 |

Day Tripper |

|

|

|

02:49 |

|

|

18 |

Drive My Car |

|

|

|

02:27 |

|

|

19 |

Norwegian Wood |

|

|

|

02:05 |

|

|

20 |

Nowhere Man |

|

|

|

02:44 |

|

|

21 |

Michelle |

|

|

|

02:42 |

|

|

22 |

In My Life |

|

|

|

02:27 |

|

|

23 |

Girl |

|

|

|

02:31 |

|

|

24 |

Paperback Writer |

|

|

|

02:18 |

|

|

25 |

Eleanor Rigby |

|

|

|

02:08 |

|

|

26 |

Yellow Submarine |

|

|

|

02:37 |

|

|

|

| Country |

United Kingdom |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

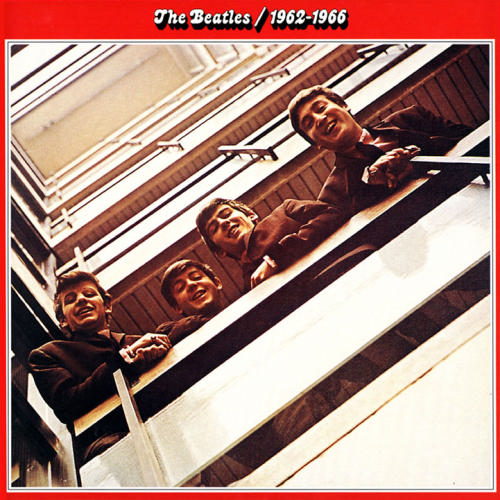

1962-1966

Date of Release Apr 2, 1973

Assembling a compilation of the Beatles is a difficult task, not only because they had an enormous number of hits, but also because singles didn't tell the full story; many of their album tracks were as important as the singles, if not more so. The double-album 1962-1966, commonly called the "Red Album," does the job surprisingly well, hitting most of the group's major early hits and adding important album tracks like "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away," "Drive My Car," "Norwegian Wood," and "In My Life." Naturally, there are many great songs missing from the 26-track 1962-1966, and perhaps it would have made more sense to include the Revolver cuts on its companion volume, 1967-1970, yet the Red Album captures the essence of the Beatles' pre-Sgt. Pepper records. - Stephen Thomas Erlewine

1. Love Me Do (Lennon/McCartney)

2. Please Please Me (Lennon/McCartney)

3. From Me to You (Lennon/McCartney)

4. She Loves You (Lennon/McCartney)

5. I Want to Hold Your Hand (Lennon/McCartney)

6. All My Loving (Lennon/McCartney)

7. Can't Buy Me Love (Lennon/McCartney)

8. A Hard Day's Night (Lennon/McCartney)

9. And I Love Her (Lennon/McCartney)

10. Eight Days a Week (Lennon/McCartney)

11. I Feel Fine (Lennon/McCartney)

12. Ticket to Ride (Lennon/McCartney)

13. Yesterday (Lennon/McCartney)

14. Help! (Lennon/McCartney)

15. You've Got to Hide Your Love Away (Lennon/McCartney)

16. We Can Work It Out (Lennon/McCartney)

17. Day Tripper (Lennon/McCartney)

18. Drive My Car (Lennon/McCartney)

19. Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown) (Lennon/McCartney)

20. Nowhere Man (Lennon/McCartney)

21. Michelle (Lennon/McCartney)

22. In My Life (Lennon/McCartney)

23. Girl (Lennon/McCartney)

24. Paperback Writer (Lennon/McCartney)

25. Eleanor Rigby (Lennon/McCartney)

26. Yellow Submarine (Lennon/McCartney)

George Harrison - Guitar, Vocals

John Lennon - Guitar, Harmonica, Vocals

Paul McCartney - Bass, Guitar, Piano, Vocals

Ringo Starr - Drums, Vocals

George Martin - Piano, Producer

1993 CD Capitol 97036

1993 CS Capitol 97036

1973 LP Capitol C1-90435

1990 LP Capitol 90435

CS Capitol C4-90435

1994 LP Capitol 97036

Love Me Do

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: As the A-side of the first Beatles single in late 1962, "Love Me Do" gave little indication of the creative songwriting genius of John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Much simpler melodically than even the group's early 1963 recordings, "Love Me Do" was a jaunty, slightly bluesy singalong, with lyrics that even by 1962 standards were bulging with elementary romantic cliches. The song, nonetheless, was notably distinguished from other British rock of the era, and if only in retrospect contained definite hints of the Beatles' strengths. First, there were those close, straining harmonies, projecting a sincerity and even a depth that was simply lacking in most other British pop artists of the period. There was also the unfettered directness of the performance, with an emphasis upon personal pronouns - "me," "you," and so forth - that Lennon and McCartney would rely upon throughout their first year or so as recording artists. And there was Lennon's bluesy harmonica, influenced by Bruce Channel accompanist Delbert McClinton (whom the Beatles had already met while supporting Channel on a British gig). In the days before multi-track recording was common, a nervous Paul McCartney had to take the low lead vocals on the brief sections of the song on which all of the instruments drop out bar the voice, since Lennon had to keep playing harmonica in the background once the music started up again. It was a modest beginning, but a fairly successful one, reaching the British Top 20. After the Beatles conquered America in early 1964, some of their 1962-1963 tracks were revived as singles, including "Love Me Do," which made number one in the U.S., although that was probably due more to the craze for all things Beatle than the merits of the specific song. With so many other Lennon- McCartney gems available, "Love Me Do" has attracted little cover action over the years, although David Bowie would jam on the tune briefly on-stage circa 1973 in his Ziggy Stardust days, and Sandie Shaw did a harmless lounge-pop version in the late '60s. - Richie Unterberger

Please Please Me

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: The first bona fide Lennon- McCartney Beatles classic, "Please Please Me" became their first British chart-topper in early 1963, and became a number three hit in the U.S. a year later, brought back from the dead after "I Want to Hold Your Hand" took off in America. Right from its very first bars, the song burst with a dynamism that was not just unheard of in British rock & roll, but had rarely been heard in rock music of any sort. After an ultra-catchy descending instrumental hook from John Lennon's harmonica, the group explodes into an exuberant, closely harmonized verse, like a rocked-up Everly Brothers. What immediately grabs the listener's attention, even the first time around, are the unexpected twists at every turn. George Harrison answers the first line with an urgent, ascending guitar riff; after the next line, everything stops except Harrison, who delivers another crafty lick to get the group into the chorus. The call and response between lead singer Lennon and the rest of the group raises the urgency yet further, resolved by the prototypically giddy ensemble harmonies as the singers deliver the title phrase. You can almost see the group shaking their moptops in euphoria at that point - a euphoria which is contagious. After negotiating a rather tortuous (by 1963 standards) bridge, the group returns to the verse one last time and has one last surprise in order. In the last chorus, the backup harmony vocals repeat the title a few times instead of dropping out, suddenly ending with an explosive series of power chords heard nowhere else on the track. Principally the work of John Lennon, "Please Please Me" had its improbable genesis as an earnestly sung Roy Orbison imitation, and was reworked and sped up on the advice of Beatles producer George Martin. You can still hear elements of Orbison in the eventual recording, particularly in the almost operatic leaps when the title is sung. However, the brashness, quirky chord changes, and overpowering enthusiasm marks this performance as the Beatles' own. Critic Roy Carr went as far as to proclaim (in The Beatles: An Illustrated Record) that "Please Please Me" "was the prototype for the next five years of British music." It was not the sort of song that could be easily matched by cover versions, although a few tried, including Petula Clark, who did a faithful and competent rendition in French in 1963. Aficionados of Beatles cover versions should also be on the lookout for a devastating mod- soul- psychedelic arrangement by obscure U.K. band the Score a few years later - one of the rare occasions on which a Beatles arrangement is totally revamped, and a fine track results (though it's still no match for the original). - Richie Unterberger

From Me to You

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: The Beatles' third single was a guaranteed smash hit right from the opening hook, a wordless singalong series of syllables that instantly lodged itself inside listeners' memories. Although "From Me to You" is one of Lennon- McCartney's more innocuous early favorites, there's a lot going on in the song melodically, indeed more than enough to keep it enjoyable several decades later. This was one of the relatively uncommon instances in which Lennon and McCartney were roughly equally responsible for the songwriting of a Lennon- McCartney original; usually one or the other was the dominant composer and singer. The equal balance is reflected in the exuberant dual harmonies; on a more subtle level, the song indicates the pair's flair for alternating major and minor chords and keys in captivating ways. That's especially apparent at the beginning of the bridge, in which the song leaps to a totally unexpected and thrillingly different key; McCartney, indeed, remains excited about that innovation, speaking about it at length on the Beatles' Anthology documentary. Most exciting of all, however, was the climax of the bridge, as typically compelling chord changes were capped by a burst of harmonized "woo!"s by the group - a trademark heard on many of their 1963 recordings, and one which helped make their sound instantly recognizable to an international audience. There was still a bluesy element to the song, however, in John Lennon's prominent harmonica solos at the beginning, middle, and end. He had done much the same thing on the Beatles' first single, "Love Me Do"; the difference was that "From Me to You" was a far more arresting and vital tune. A number one hit in the U.K., it was almost immediately covered for the American market with a similar arrangement by Del Shannon, who, in fact, had greater initial success with the song in the States than the Beatles did, although neither version rose above the bottom of the charts. For some reason, it wasn't revived as an A-side in the U.S. in early 1964 during the initial Beatles invasion, although it did make the middle of the Top 100 as a B-side. No more famous covers were forthcoming, but it no doubt found its way into the set of numerous bands in the mid-'60s; the Bobby Fuller Four, for instance, played it live, as tapes that were eventually released proved. - Richie Unterberger

She Loves You

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "She Loves You" was the song that made Beatlemania a rage in England in late 1963, becoming the most popular single that had ever been issued in Britain up to that time. Although it initially (and inexplicably) flopped in the U.S., it was dusted off a few months later in the wake of "I Want to Hold Your Hand" and topped the charts stateside, where it became just as linked to the early Beatles' image as it was in the U.K. From the opening drum roll, "She Loves You" takes no prisoners, immediately charging into its indelible "yeah, yeah, yeah" hook; it was George Martin's successful brainstorm to move the chorus to the very beginning of the song. Although lyrically it was, like most of Lennon- McCartney's early compositions, an elementary boy-girl situation heavy on the pronouns, there was a twist in that it was related in the third person, not the first or second. A small innovation, perhaps, but one that the Beatles were proud of. Instead of telling a girl how much they were in love, they were virtually scolding a friend for throwing away the love of a lifetime. What really won over listeners' hearts, though, were the usual block harmonies, clever alternation of major and minor chords, and particularly the ends of the verses, in which the group simultaneously let out with explosive "woo"s. Lennon and McCartney were also especially proud of ending the choruses (and the song itself) on a sixth chord, which they initially believed had never been done before. It fell to producer George Martin to inform them that others had used it, such as Glenn Miller, but that didn't take away from its freshness in a rock context. Those "yeah, yeah, yeah"s and "woo!"s would annoy many a commentator as infantile when the Beatles first broke big. The kids, of course, knew better and embraced them as positive affirmations of the boundless enthusiasm of youth. Today those commentators are forgotten, and the Beatles' "She Loves You" is still played regularly. - Richie Unterberger

I Want to Hold Your Hand

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "I Want to Hold Your Hand" was one of the most important songs in rock history. It was the first the Beatles song to become a hit in the United States, rocketing to number one in early 1964; it was the song most responsible for making the group an international phenomenon; and it was the song that launched the British Invasion. And, historical concerns aside, it was a great song. As with all of the classic Beatles singles, it went for the jugular right away, with stuttering opening chords that made a sudden dramatic leap upward. (These were inspired by, of all things, an album of experimental French music that John Lennon heard at the apartment of Robert Freeman, the Beatles' photographer that lived in the flat below him.) The verse hinged upon another one of those unexpected minor chords that Lennon and McCartney were so fond of deploying in their early work, ably complemented by a growling low guitar riff from George Harrison that was somewhat like an updated variation of Duane Eddy. At the end of each verse, the Beatles, in unison, jump a whole octave to almost shriek the word "hand." The softer, almost ballad-like bridge is an effective contrast to the more highly charged verses, particularly when the group revisits that opening stuttering guitar figure to deliver the exclamation "I can't hide," overflowing with giddy enthusiasm, impatience, and celebration. As usual, the Beatles threw in other unexpected surprises at the very end, with the second to last repetition of the title going to an odd minor chord before the song resolves itself on an elongated final "hand." The lyrics have been faintly ridiculed by some critics for the tame sexuality of the title phrase, but as is the case with many early Beatles tunes, the primness of the words is totally belied by the delivery: the song tingles with sexual longing, desire, and delirious anticipation of fulfillment. Few of the listeners who bought the single bothered to break the tune down with such analysis. What they knew only was that the song and record were irresistible, and sounded like nothing that had ever been heard before. It wasn't only teenagers that were affected; as Bob Dylan said about Beatles songs such as "I Want to Hold Your Hand," "They were doing things nobody was doing. Their chords were outrageous, just outrageous, and their harmonies made it all valid." It was a unique, definitive performance that could not be easily approached by covers, although several tried, with mixed results. Among the more bizarre instances were Arthur Fiedler & the Boston Pops Orchestra, who actually took an instrumental cover to number 55 in 1964, and Texas psychedelic band the Moving Sidewalks (including future ZZ Top guitarist Billy Gibbons), who did a lurching heavy psych version in the late '60s. - Richie Unterberger

All My Loving

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "All My Loving" was arguably the best LP-only track the Beatles did before 1964. Although credited to Lennon and McCartney, this was an early instance in which one of the pair ( McCartney in this case) was responsible for virtually all of the songwriting - a situation which would become much more common as the years passed, to the point where almost all Lennon- McCartney compositions were actually composed almost solely by one or the other. Immediately the song overwhelms with the urgent optimism that was one of the Beatles' early trademarks, driven along by speedy guitar triplets. For all of its almost utopian feel-goodism, "All My Loving"'s melody has a bittersweet quality that keeps the tune from even approaching sappiness, particularly on the chorus, when McCartney's vocal is complemented by haunting descending harmonies. It was this bittersweet element that separated the Beatles from not only their Merseybeat competitors, who were often overly jaunty or sentimental, but also from most groups that have tried to imitate or re-create the Beatles over subsequent decades, which usually don't take the time or possess the imagination to bother with trivialities like minor chords. George Harrison's guitar solo is brief but powerful, and rightly cited as proof that he had become Carl Perkins' most brilliant disciple. Not content to simply fade out the chorus, the group drives home the tune with a repetition of the chorus in which McCartney breaks loose with some exhilarating pleas and falsettos. "All My Loving," and not "I Want to Hold Your Hand" as some might guess, was the first song that most Americans saw the Beatles perform, as the opening number of their appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964. It was not released as a single in America, but in all likelihood could have been a huge hit if it had been. - Richie Unterberger

Can't Buy Me Love

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Can't Buy Me Love" was the first single to be released by the Beatles after the group had established themselves as Transatlantic superstars. Although it quickly topped the charts in both the U.S. and U.K., it's been somewhat underestimated by history, coming in the wake of the "She Loves You" and "I Want to Hold Your Hand" monsters, and just prior to "A Hard Day's Night." That aside, it's another great early Lennon- McCartney tune, and one of their raunchiest rockers, sung and principally written by Paul McCartney. It kicks off with yet another arresting opening, in which the Beatles launch directly into the chorus rather than the verse, as they did with "She Loves You," again on the suggestion of George Martin. The verses are rock in the Little Richard- Chuck Berry tradition, set off by the non-bluesy minor chords of the chorus, a Beatlesque trait that was beyond the reach of 1950s rock. Although the words were basic romantic phrases, the Beatles were beginning, if only slightly, to reach out beyond their simpler pronoun-heavy hits of 1963. Not caring too much for money, 'cause it can't buy you love - that's a timeless sentiment, emblematic of the devil-may-care immediacy of youth, perhaps. But it's also a value that many can agree, even in the 21st century, the world could use a lot more of. The track is further distinguished by a bluesy, engagingly raw guitar solo in the instrumental break, and brought to a close by an almost orgiastic world-less song-sigh at the very end. It was this cut that was chosen, most appropriately, to play on the soundtrack of A Hard Day's Night in which the Beatles romp around a huge empty field, brilliantly reflecting the group's carefree appetite for living in the moment. - Richie Unterberger

Hard Day's Night

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: Perhaps no sonic flourish epitomizes the spirit of the Beatles - and indeed the entire British Invasion - more than the jubilant 12-string guitar chord that opens "A Hard Day's Night." (That George Harrison chord, incidentally, is Gm7 add 11.) It was that chord, and song, which introduced the movie of the same name, a film that in turn embodied Beatlemania at its apogee. "A Hard Day's Night" had a depth and shimmer to the production greater than any previous Beatles track, due in large part to that 12-string guitar. The song itself mirrored the Beatles' boundless enthusiasm more than almost anything else Lennon- McCartney wrote, particularly when McCartney joined Lennon in the closing lines of the verse, singing of getting home to their loves and feeling alright with a joy and anticipation that is downright fierce. Effective juxtaposition of bridge and verse is a Beatles specialty, but on "A Hard Day's Night" they outdid even themselves, as the Lennon-sung verse yields to a more wistful, haunting bridge sung by McCartney. McCartney is one of the greatest upper-register singers in rock & roll, and he was rarely better or more effervescent than he was when he reached the bridge's climax in "A Hard Day's Night." The instrumental break was garnished by an imaginative keyboards by producer George Martin, and the fade closed on a series of an eerie unaccompanied circular 12-string guitar notes by Harrison. Lyrically the title of "A Hard Day's Night," allegedly taken from a comment by Ringo Starr, was the first instance of a Beatles lyric to reflect Lennon's love of puns (which was reflected much more strongly in his 1964 book In His Own Write). The body of the actual lyric, sung by a guy who doesn't mind slaving away at work to buy his lover goodies since she makes him feel so good when he comes home, might not be so apropos today, when women have much more presence and equality (in the workplace and at home) than they did in the mid-'60s. It might be getting a little too hung up on PC mores to dwell on that; certainly the main point of the song was to express an overall joie de vivre, and it excelled at doing so. It was also a big smash, reaching number one in both the U.S. and U.K. The most noteworthy cover version was a live one by Otis Redding, who (as he did with songs by both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones) accentuated its funkiest and most soulful properties, managing to make it over into a soul tune without embarrassing either himself or the composers. - Richie Unterberger

And I Love Her

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "And I Love Her" was one of the Beatles' most outstanding ballad love songs, and a highlight of the soundtrack to their movie A Hard Day's Night. Sung and almost wholly written by Paul McCartney, it is the composition that most aptly illustrates McCartney's knack for what critics often term a high "haunt count": an almost unsurpassed ability, in other words, to craft lovely haunting melodies. Indeed, the melody was almost Mediterranean in feel, a quality emphasized by the primarily acoustic arrangement, samba-like rhythms, and bongos and claves (used in place of traditional rock drums). The arrangement was itself an indication, if only in retrospect, that the Beatles were beginning to look beyond conventional structure and production when devising their studio tracks. In "And I Love Her," their structural daring was further reflected in the change to a higher key when the guitar solo began; when the main guitar riff brought the song to a close, the predominantly minor-key tune ended with an authoritative major chord heard nowhere else in the tune (a device also used by other British Invasion groups of the time). Although not released as a single in their native Britain, "And I Love Her" was pulled off the A Hard Day's Night soundtrack in the wake of the "A Hard Day's Night" single for release as a 45 in the United States, and deservedly did quite well, just missing the Top Ten. As a romantic ballad, it also attracted more mainstream cover versions than many of Lennon- McCartney's early songs did, including one by soul-pop singer Esther Phillips, who made the middle of the Top 100 (and almost made the R&B Top Ten) with her gender-switched "And I Love Him." Also worthy of a listen is an obscure but fine mid-'60s reggae version by a very young Wailers, then unknown outside of Jamaica. - Richie Unterberger

Eight Days a Week

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: When it was first released in Britain in late 1964 on Beatles for Sale, "Eight Days a Week" was just an album track. America's appetite for Beatles product, however, was insatiable at this point, and the bigger and more affluent U.S. market far more accommodating for songs that could be sold on singles. So "Eight Days a Week," like "Twist and Shout" and "Do You Want to Know a Secret?" before it, and like "Yesterday" and "Nowhere Man" after it, was released on a 45, although it was not designed by the Beatles themselves as a featured single, and did not appear as such in their native U.K. Although it made number one in the States, it is not one of the songs that first comes to mind when early Beatles classics are summarized. That hardly means that it was forgettable; in fact, it was damned good. There are few Lennon- McCartney songs that are bouncier and cheerier than "Eight Days a Week," although there's plenty of yearning grit in John Lennon's lead vocal, particularly at a point near the end of the song, where he breaks into a brief peculiar wordless melisma. He's superbly supported by Paul McCartney's harmony vocals, and the necessary mixture of light and shade is supplied by the bridge, which suddenly goes into emphatic minor chords. At one point during this bridge, all the instruments drop out, leaving the voices unaccompanied for a line; everything comes to a dead stop for a nanosecond. Then a shoe-drop of Ringo Starr drums kicks the music into gear again, and the melody brightens as it explodes back into the verse; the Beatles' spirits could never be dampened for long. Becoming ever bolder in their studio experimentation even at this relatively early date, the track begins with a gradual fade-in, a device which had rarely been employed in rock music, and served to heighten the drama and immediately seize the listener's attention. Although the lyric is for the most part a standard celebratory love song, the title phrase "eight days a week" (like a previous Beatles title, "a hard day's night") betrays Lennon- McCartney's growing knack for unusual wordplay - a trait that would soon become far more commonplace. Lennon, never the best judge of the Beatles' own work, was surprisingly disdainful of the song in a 1980 Playboy interview, claiming (erroneously) that "it was never a good song. We struggled to record it and struggled to make it into a song. It was [ McCartney's] initial effort, but I think we both worked on it. I'm not sure. But it was lousy anyway." - Richie Unterberger

I Feel Fine

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "I Feel Fine" was a typically first-class 1964 Beatles single, topping the charts on both sides of the Atlantic. It was distinguished from its predecessors by a more complex guitar sound, particularly in its introduction, a sustained plucked electric note that after a few seconds swelled in volume and buzzed like an electric razor. This was the very first use of feedback on a rock record. It's been claimed that others (such as the Who, the Yardbirds, and Creation guitarist Eddie Phillips) had developed guitar feedback, or something approximating it, live before the Beatles did "I Feel Fine." It seems inarguable, however, that the Beatles were the first to use it on disc; probably no other group had the clout to get away with that experiment in late 1964. Anyway, the brief feedback was but a preamble to a bubbly Beatles song paced by a brilliantly active and difficult George Harrison guitar riff, inspired perhaps by a similar line in obscure soul singer Bobby Parker's 1961 single "Watch Your Step." Ringo Starr deserves commendation himself for the series of four urgent drum beats that kicks off both the first verse (after Harrison has gone through the principal riff) and the return to the verse after the instrumental break. The singing, as usual, was John and Paul's show primarily, with particularly sumptuous harmonies counterpointing John's lead in the bridge. Rather than coming to a cold stop after the last chorus, an unaccompanied electric guitar continues to noodle as Lennon wordlessly scats, while the Beatles faintly bark (like dogs, yes) in the background - another imaginative ending from a group that used them often. Lennon, the more prominent songwriter than McCartney on "I Feel Fine," has rightly been noted as having the more doubtful and pessimistic view of the pair in his lyrics, even in the early days. There's no trace of doubt or pessimism, however, in "I Feel Fine," which certainly is one of his most positive and optimistic musical statements. - Richie Unterberger

Ticket to Ride

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: With their first 1965 single, "Ticket to Ride," the Beatles not only notched up their usual worldwide chart-topper, but also made it clear that they were not going to rest on their laurels and continued to evolve at a furious rate both musically or lyrically. The opening circular riff, played on 12-string guitar by George Harrison, was a signpost for the folk-rock wave that would ride through rock music itself in 1965. Certainly Harrison's playing, on this and other Beatles tracks, was a big influence on the best and first folk-rock group, the Byrds, whose Roger McGuinn used similar 12-string electric guitar riffs. The rhythm parts on "Ticket to Ride" were harder and heavier than they had been on any previous Beatles outing, particularly in Ringo Starr's stormy stutters and rolls. Particularly memorable was the point in the chorus at which all the music dropped out except for Lennon's voice and a shock wave of reverbed guitar, immediately recharged by imaginatively varied Starr drum figures. The bittersweet verses segued into a faster and more upbeat bridge, brought to a close by some shrill and bluesy hard rock guitar, later revealed to have been played by Paul McCartney (usually the group's bassist) rather than Harrison. The combination of all of these elements, one presumes, led John Lennon to call "Ticket to Ride" "one of the earliest heavy metal records ever made," a somewhat incorrect characterization; it was heavy and metallic, but not at all like heavy metal music. Lyrically, "Ticket to Ride" is one of the more prominent instances of principal writer Lennon's sullen, bitter hurt at being rejected, as difficult as it might have been to imagine any girl running away from him on a train in early 1965. He was, after all, spending much of his time running away from girls running after him at this point in his life. As an artist, however, Lennon's gift was sounding utterly convincing anyway when relating his tale, taking steps away from the simple words of 1963-1964 Beatles compositions with an increased use of contemporary slang. There was also a very subtle pun in the title: Ryde, pronounced the same as ride, is a British town on the Isle of Wight. As some critics have noted, the Beatles never sounded too unhappy, even when the words were unhappy. That's the case with "Ticket to Ride," courtesy of McCartney's energetic harmonies and a bridge in which the despair of the verses is set off by a somewhat more confident, boasting attitude of the bridge, implying that the girl might have cause to regret what she's doing when she thinks about it. The song's mixed emotions are driven home by the surprising ending. After the final chorus comes to a brief, cold stop, the track suddenly speeds into double-tempo, with happy-go-lucky repetitions of "my baby don't care" as the tune fades out. It's as if the singer is trying to affect a carefree attitude to cover up the devastating emotional blow he's just been dealt; it's a deftly ironic and emotionally complex conclusion to the classic. - Richie Unterberger

Yesterday

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Yesterday" is the most frequently covered Lennon- McCartney song ever, and indeed one of the most frequently recorded and performed popular music standards of the 20th century. The endless repetitions of the number, from contexts ranging from lounge jazz bands to TV variety shows and elevator muzak, have dulled the senses as to how fresh it actually did sound when it came out in mid-1965. Producer George Martin immediately sensed that the ballad, sung and wholly composed by Paul McCartney, would not work as a standard rock group arrangement. It was decided to augment McCartney with a string quartet - the first time strings had ever been used on a Beatles session. McCartney, therefore, is the only Beatle featured on the recording, playing acoustic guitar and singing; it is essentially a solo Paul McCartney recording, although the band would work up a string-less live version to play on their final world tour in 1966. "Yesterday" is a supreme example of McCartney's talent for writing a classic, melancholic, memorable melody that was sad, but not gloomy or dirgey. The lyrics were direct and evocative of one of the most universal human emotions: nostalgia for better times in general and for a lost love in particular. To his credit, McCartney did not overplay the frankly sentimental lyric, singing the tune in a gentle, understated, sympathetic fashion that steered clear of self-pity. George Martin also deserves credit for not laying on the schmaltz with bombastic over-production, as many, perhaps most, producers would have done in the situation. Shrewdly, it was decided to have McCartney sing the first verse accompanied only by his acoustic guitar; the string quartet is introduced in the second verse, offering subtle support rather than overwhelming the vocalist, but introducing slightly more complex and elaborate counterpoints as the tune progresses. There's that point in the second bridge, for instance, where the cello suddenly throws in a groaning lick as a Greek chorus of sorts. For the very last line, McCartney hums wordlessly, as if he's said all he can and can only self-ruminate about his sadness. When first released, "Yesterday," oddly, was relegated to an LP track on the British Help album (it did not feature on the Help! soundtrack either). In America, Capitol Records knew a monster hit when they heard one; the label put it out as a single in late 1965 and it immediately soared to number one for a full month. By that time, the never-ending wagonload of cover versions had already begun. Not only did it sound like an instant standard, it was more adaptable to a set of pop and middle-of-the-road performers than virtually any other Beatles songs were, particularly as so many Lennon- McCartney compositions were idiosyncratic and difficult to pull off in the hands of others. In Britain, for instance, balladeer Matt Monro got into the Top Ten with his cover in the fall of 1965, when the Beatles' version was barely off the presses. It would take dozens of pages to list all of the covers of "Yesterday" that have been recorded, and many others have been performed live but not recorded by acts ranging from superstars to junior high school bands. The most well-known one, perhaps, is the soul version done by Ray Charles for a Top 30 hit in 1967, although John Lennon, for one, said he did not like Charles' recording. - Richie Unterberger

Help!

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Help!" was a transatlantic number one single for the Beatles in mid-1965, serving the dual purpose of giving them an appropriate theme song for their second movie, also titled Help! On strictly musical terms, the track was great. That was especially true of its ominous descending guitar lines by George Harrison, which punctuated the ending of the verses and also added an appropriately cinematic sense of dread to the sections in which lead singer John Lennon seemed especially despondent. Like numerous classic Beatles singles, it opens not with the verse, but with the chorus, creating a sense of immediacy which sweeps the listener into the spirit of the thing almost before it's registered that the record has begun. Note, however, how the vocal and melody differ slightly on this opening bit from the choruses on the rest of the record: just one of many ways in which the Beatles were able to stay ahead of the rest of the pack, which lacked the care or imagination to come up with such clever passages. They also switch to a different, more ominous melody for the final "help me" exclamations (one of which, by John Lennon, sounds particularly fearful) at the very end of the song, cooling things out at the last moment with an a cappella "woo." What truly set this apart from other Beatles records up to that time, however, were the words, which betrayed a new level of sophistication and uncertain ambiguity. On the surface, "Help!" was another fun Beatles tune, a suitable theme for a movie which saw them joke their way through scene after scene in which their very lives were in peril. On a deeper level, it was a plea, from John Lennon specifically, for psychological help from a woman or from anything or anybody. As he later claimed, for all the Beatles' enormous success in the mid-'60s, he was personally unhappy and unsatisfied. "Help!," viewed from that angle, was a confession of his insecurities, showing (as did other of his songs from the era, such as "I'm a Loser" and "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away") a definite though not blatant Bob Dylan influence. Greil Marcus once wrote in -The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & oll that " the Beatles' optimism prevailed even when they tried to sound desperate, which sometimes made them sound sappy," using "Help!" as an example. The Beatles' optimism does shine through on "Help!," particularly on the ecstatic harmonies on the title word when the choruses end. At those points they don't sound desperate - they sound happy. But they don't sound sappy. It was another instance in which the counterbalance of moods within Beatles songs was matchless. If you're looking for strange cover versions of "Help!," go no further than the one by the Damned on the flip side of the 1976 "New Rose" single (the very first British punk 45). There also a bizarre slowed-down lounge/ soul interpretation by John's Children lead singer Andy Ellison, unreleased at the time it was recorded in the late '60s, but included on the John's Children archival EP Midsummer Night's Scene. - Richie Unterberger

You've Got to Hide Your Love Away

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: One of the highlights of the Help! album and soundtrack was "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away," a ballad that showed the Beatles' increased interest in folk-rock in general and the influence of Bob Dylan upon principal composer John Lennon in particular. The acoustic guitar-oriented arrangement, percussionless save for some tambourine beats, contained one of Lennon's most world-weary vocals. As with several Lennon- McCartney compositions from the late-1964/early-1965 period in which Lennon was the chief writer - "I'm a Loser," "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party," and "Yes It Is" were others - there is a palpable sense of shame at self-duplicity and self-pity. Dylan's style is felt in the heavily accented guitar strums and grainy vocal, particularly in the singalong chorus, where Lennon suddenly sing-shouts "hey!" before singing the title. "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away" was the first Beatles session (excepting "Love Me Do," on which they used session drummer Andy White) to feature a musician other than the Beatles or George Martin, that being flute player Johnnie Scott. Scott played on the brief instrumental section that ends the track, adding a jazzy and lighthearted touch that might have helped the performance from being too lugubrious. A Top Ten hit cover of "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away" came out later that year by British pop-folk group the Silkie (managed by Beatles manager Brian Epstein), with Lennon producing, Paul McCartney contributing guitar and arrangement, and George Harrison on guitar taps and tambourine. - Richie Unterberger

We Can Work It Out

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: In tune with the gentle, optimistic folk-rock that was all the rage in late 1965, "We Can Work It Out" was a number one single in both the U.S. and U.K., sharing more or less equal A-side status with its flip, "Day Tripper," although "Day Tripper" got less airplay due to the slightly controversial content of its lyric. Although more of the tune was written by Paul McCartney than John Lennon, it was also an outstanding example of how disparate sections written by each could be combined into one song that was more than the sum of its parts. (Indeed, perhaps only "A Day in the Life" is a more outstanding example.) McCartney's sunny, look-on-the-bright-side outlook dominates the lilting verses; the singing of the title on the chorus especially radiates hope and conflict resolution. The necessary darker component of the human equation is supplied by Lennon's bridge, which descends into minor chords and radiates impatience, doubt, and disillusionment. Much spice is added to the basic folk-rock arrangement by John Lennon's harmonium, which gives the tune a faintly old English folk air. It was also a masterstroke to switch the tempo to waltz-time for part of the bridge, which emphasized the more downcast and forlorn lyrics of Lennon's section. "We Can Work It Out" was fodder for one of the most commercially successful Beatles covers of all time when Stevie Wonder took a funky soul version into the Top 20 in 1971. - Richie Unterberger

Day Tripper

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Day Tripper" was the co-A-side, if that word could be used, of the late 1965 single that had "We Can Work It Out" on the other side. It was a worldwide number one, although "We Can Work It Out" got more airplay, due in part to "Day Tripper"'s somewhat risque lyrics. "Day Tripper," you see, could refer to a trip that was drug-induced; it was also slang for a prostitute, some thought. In truth, it is doubtful that most of the young people that were responsible for the bulk of Beatles record sales in late 1965 were aware of such supposed double entendres. What grabbed them then and grabs people now is the dynamic rock-soul guitar riff, partially inspired, as was the riff of "I Feel Fine," by the guitar lines heard in Bobby Parker's 1961 soul single "Watch Your Step." The "Day Tripper" riff was quite a riff, though, spiraling up the scale with a funky grace, changing keys as the song itself changed keys, particularly in the instrumental break, where the keys reached their highest changes and ensemble harmonies pushed the tension to the brink before the quasi-rave-up segued back into the verse. The track's a good showcase for the Beatles' somewhat underestimated talents as bona fide soulful vocalists, particularly in McCartney's gritty execution of lines during the verses, and the falsetto that Lennon breaks into during the final chorus. Getting back to those mildly controversial lyrics, "Day Tripper" is a prime illustration of Lennon and McCartney's growing talent for incorporating contemporary slang into their songs. Both of the composers commented, in fact, that "Day Tripper" was not so much about acid trips as about people - "day trippers" - who pretended to be hip for brief periods, day trips, of time without being willing to commit to adventurousness on a full-time basis. It could also be properly read as a gripe about women who teased without going all the way - a time-honored subject, for better or worse, in popular music in general and in rock, R&B, and the blues in particular. One of those bits of slang Lennon and McCartney threw in that no doubt went over the heads of the kids in 1965 - and still goes over the heads of most adults today - was the line about the day tripper being a big teaser, which they actually sang as "she's a prick teaser." One major performer to recognize the inherent soulfulness of "Day Tripper" was Otis Redding, who put his more funk-based cover on his 1966 Dictionary of Soul album; another was Jimi Hendrix, who performed it on the BBC the following year. - Richie Unterberger

Drive My Car

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Drive My Car" was one of the best numbers on the Beatles' Rubber Soul album, one which saw both their musical and lyrical horizons visibly opening. Although John Lennon was in general ahead of Paul McCartney in expanding his lyrics in more ambitious and experimental directions, this story-song was principally the work of McCartney, with some assistance from his contractual songwriting partner. The verse is based around a funky two-chord groove which ascends to a higher level at the very end, a suitable bedrock for a commanding McCartney hard rock vocal. Far more surprising is the chorus, with its tortuous jazzy key changes, a quality reinforced by the bursts of jazz piano that follow the first two lines. While initially the song seems like the standard macho boasting of some guy showing off his car, it transpires that actually the girl in the song is leading the narrator on by half-hinting that she'll let him be her chauffeur, and maybe be his lover too. That's a subtle, one might say almost O. Henry-like, slant that was most likely totally beyond the reach of the usual Californian hot-rod act, or most other pop and rock singers for that matter. The most ironic touch, however, was applied when the Beatles merrily sang "beep beep" at the end of the chorus' punch line: a nifty way of making nonsense words compliment the images and the sounds. An especially wiry guitar solo was a nice cap to the understated, faintly nutty satire of what was nonetheless a very good-natured tune. The best-known cover of "Drive My Car" - not one of Lennon- McCartney's more frequently interpreted compositions - was by jazz singer Bobby McFerrin in the 1980s. - Richie Unterberger

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Norwegian Wood," in addition to having a lovely melody and folk-based arrangement, was one of the first Lennon- McCartney songs to excite as much comment for the words as it did for the music. As with much of Rubber Soul, the mood was very much a folk-rock one, with the subtle ghost of Bob Dylan hovering over principal lyricist John Lennon's wordplay. Dylan, in fact, recorded a semi-parody of "Norwegian Wood," "Fourth Time Around," on Blonde on Blonde, which was okay but not as good as the tune it was gently mocking, and not as funny as it might have been intended to be. "Norwegian Wood" was the story of an illicit affair, enigmatically worded out of necessity, as Lennon was married at the time. The hazy but evocative approach to the lyrics, however, probably worked better than a much more direct sketch would have. "Norwegian Wood" has a sting because, in spite of the rather bemused air with which Lennon delivers the vocals, it's unclear who (if anyone) is taking advantage of whom in this secret tryst. He had a girl once, the narrator sings; or, perhaps, did she have him? Why wasn't there a chair to use after she told him to sit down? And why did he sleep in the bath when the scene was apparently set for consummation of their relationship? Resignation is tinged with lonely despair when the narrator wakes to find that the "bird" (British slang for woman) has flown the coop. It was speculated that the fire the singer lit with Norwegian wood was a marijuana joint, or, more mean-spiritedly, that he'd burned the house down. In all, there was more than enough ambiguity and ingenious innuendo to satisfy even a Dylan fan. For listeners who were more Beatles fans than Dylan ones, the group had sure come a long way since "She Loves You" just two years back. The power of the track is greatly enhanced by McCartney's sympathetic high harmonies on the bridge, and its exoticism confirmed by George Harrison's twanging sitar riffs, the first use of that Indian instrument on a rock record. - Richie Unterberger

Nowhere Man

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Nowhere Man" was a landmark Beatles song, as their very first original composition not to deal with romantic love in its subject matter in any way whatsoever. True, Lennon- McCartney's songwriting had started to edge toward new themes in late 1964 and 1965, sometimes framing events in stories and yielding windows to highly personal emotions, particularly when John Lennon was the dominant composer. However, even clever and sophisticated lyrics such as "I'm a Loser," "Help!," and "Norwegian Wood" all at least alluded to a woman who had left, or a romantic situation, or a woman who might provide emotional comfort. "Nowhere Man," sung and wholly composed by Lennon, was their first out-and-out venture into writing about the world, not just interpersonal romance, in step with recent and simultaneous innovations along those lines by challenging peers such as Bob Dylan, the Byrds, the Kinks, and the Yardbirds. While it's not exactly a topical song, there is certainly some social commentary evolved in this dispiriting portrait of a nowhere man without opinions, feelings, or direction. "Nowhere Man" is, in a sense, Everyman in modern Western life: a point driven home by the gentle question-reminders that he might be a little like you and me. Lennon soon let slip that the "Nowhere Man" in the song was none other than himself, which makes you wonder whether Patrick McGoohan was taking notes on these kinds of songs when he came up with the premise for his classic TV series The Prisoner. A trait that distinguished "Nowhere Man" from similar songs about empty modern men by artists like Bob Dylan and the Kinks (whose "Well Respected Man" came out at about the same time) was the empathy and sympathy the Beatles showed toward their subject. That's especially prevalent in the bridge, in which the nowhere man is implored to look within himself and hope for someone else to come to his aid and comfort. Considering the subject matter of this song, "Nowhere Man" is remarkably upbeat in melody and execution, particularly in its three-part harmonies, best heard on the opening a cappella pass through the chorus. George Harrison contributes a sparkling guitar solo in the instrumental break, which, unusually, comes one-third through the track, not at the halfway or two-thirds point, as instrumental breaks usually do. Harrison also offers nice low, fluid responsive guitar lines to the end of each verse, and McCartney adds a great high harmony - not used at any other point in the track - to the very last repetition of the chorus, as if to add emphasis. Although it was just a Rubber Soul LP track in Britain, "Nowhere Man" was held off the initial U.S. release of that album and issued as a single in early 1966 - the last time a Beatles single was issued in the States without appearing in the format in the U.K. Perhaps that was not a decision the Beatles were in favor of, but the commercial appeal of the song was undeniable, as the single reached number three. - Richie Unterberger

Michelle

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: On an album, Rubber Soul, characterized by compositions that brought the Beatles into far more sophisticated lyrical territory, "Michelle" was something of a throwback to their simpler earlier romantic tunes. Melodically, however, it was the equal of anything else on the record, and actually of most anything else composed by Lennon- McCartney. Like "Yesterday," it had the air of an instant standard. While it hasn't been covered as much as "Yesterday" has (nothing has been covered as much "Yesterday" has), it did indeed become pretty much a popular music standard. Leading off the tune, and reappearing in other sections, was a haunting descending guitar line, plucked in a rather Greek style: a trait which can be detected in the guitar work on a few other Beatles ballads (notably "And I Love Her" and "Girl"). It might have been too much on the sentimental side for the group's most rock-oriented fans, but certainly the melody was memorable and the harmonies heavenly. McCartney put on his best crooner charm for the vocal, moving into French for much of the time. A bit of grit is supplied by the bridge, in which McCartney repeats "I love you" in a rapid repetition that is similar to the jazz scat style. It was eventually revealed that this bit was inspired by Nina Simone's somewhat (though hardly exactly similar) repetitions of the exact same phrase in her jazzy cover of "I Put a Spell on You." Also jazzy is George Harrison's guitar solo, which could have been used for some early-'60s cool jazz session. The melody is varied slightly to set an air of finality to McCartney's declaration of love for his French femme fatale on the final section (which lyrically mimics the instrumental guitar line that led off the track). The Beatles end, as was sometimes their wont, on a major chord in this minor-keyed tune, adding to the pleasing effect of a melody bound to linger in the memory. As with "Yesterday," other acts were quick to spot the tune's potential; the Overlanders took it to number one in the U.K. in early 1966 (although it failed to hit in the U.S.), while David and Jonathan took a pop-slanted interpretation to both the American and British Top 20 at the same time. - Richie Unterberger

In My Life

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "In My Life" is perhaps the finest song on Rubber Soul, and one of The Beatles' greatest compositions. Usually assumed to have been written in the most part by John Lennon (although McCartney has disputed this), "In My Life" is an ode to childhood, and the band's native Liverpool. The lyrics are heartbreaking - "There are places I remember, all my life though some have changed/Some forever not for better, some have gone and some remain" are just the opening lines, and the song progresses through a series of lovely images, before it turns into a love song by it's conclusion. The chord progression is unorthodox yet utterly transcendent, and the organ break, played by George Martin is quite audacious. "In My Life" is simply one of the best songs The Beatles ever wrote. - Thomas Ward

Girl

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Girl" might have been produced at the very end of the period in which the Beatles were still writing love songs exclusively, but as Beatles love songs go, it was one of their most melancholy and complex. In both tempo and melody, the composition, primarily the idea of John Lennon (completed with considerable help from Paul McCartney), betrayed the Beatles' oft-overlooked debt to Greek music in their ballads (see also "And I Love Her" and "Michelle"). The guitar work on "Girl," however, was more likely to generate specific comparisons to Greek music than "And I Love Her" and "Michelle" were, or indeed than any other Beatles song was - the instrumental reprise of the bridge near the end, indeed, is very much like a Greek dance. The Beatles' view of the "Girl" in the song, if not of womanhood as a whole, is seen to be one that regards her as a simultaneous bitch and goddess. That is not the most enlightened view of women, many would agree, but it is nonetheless one held by many men in both prose and real life. The girl of the composition is seen as a source of both delight and torture, of both pain and pleasure, both a necessary source of succor and an oppressive burden to support. The narrator's resignation to this situation is ingeniously reflected by one of the Beatles' most unusual choruses, consisting solely of a couple of falsetto repetitions of the one-word title, to which Lennon responds with a heavy sigh, as if sagging in exasperation. The words take an especially savage turn in the bridge, as the tempo suddenly doubles while Lennon wails about a woman who humiliates him with a pleasure that verges on the sadistic. Lyrics near the end of the song commenting on whether the girl has been taught that pain would lead to pleasure, and that a man must break his back to earn his leisure, are almost Biblical in tone. Rather surprisingly, McCartney revealed these phrases (in his semi-autobiography Many Years From Now) to be his work, rather than Lennon's as many had supposed. The high backup harmonies on the bridge, incidentally, incorporate one of the more outrageous inside jokes the Beatles were increasingly apt to sneak into their recordings: although these sound on a casual listen like "dih-dih-dih-dih" scats, Lennon eventually let slip that they were actually singing "tit-tit-tit-tit." - Richie Unterberger

Paperback Writer

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Paperback Writer" was a number one single in 1966, and as was habitual on Beatles singles, pushed the group into new lyrical and sonic terrain. This tough mod rocker featured more assertive guitar chords, leads, and especially bass than any pre-1966 Beatles recording had. The winding guitar figure that runs through the song shows a similarity to the then-recent work of the Who in particular, without sounding blatantly imitative or derivative. Paul McCartney, the song's lead vocalist and principal author, had been fighting for some time to get a heavier, more prominent bass sound on Beatles tracks, and succeeded in truly doing so for the first time here. His intricate lines boom with an authoritative fullness that seems to threaten to shatter the stylus; indeed, it was (inaccurately) claimed by British technicians of the time that they couldn't successfully master such bass playing on vinyl for fear that the needle would jump. Just as clever and innovative on "Paperback Writer" were the vocal arrangements, gripping the listener right from the first bars, which consisted of a densely layered a cappella harmonization of the chorus. Repeated at various strategic points throughout the song, the counterpoints and falsettos on this brief burst of harmonies resembled the most complicated ones of the Beach Boys, particularly in the falsetto part, naturally. The Beatles' gift for sudden surprise came into view at the end of the verses, in which an emphatic enunciation of the title phrase exploded into a supersonic, slowly decaying echo. This was especially dramatic when all of the instruments dropped out, leaving only the reverberating voices to fade before the music kicked into gear again. On top of all this was a lyric - about a struggling novelist - that fit in well with the ethos of swinging London, and like "Nowhere Man" a few months before, served notice that the Beatles were going to write songs about the world of their time that had nothing to do with romantic love. It may be that it was John Lennon that generally made the first step in broadening the Beatles' lyrical views throughout their career, but it must also be noted that McCartney was extremely quick to pick up on them and follow that path brilliantly as well. "Paperback Writer" would be typical of much of McCartney's non-love song work in that it wittily set out an observational story, situation, or character that seemed to have little to do with his own deep personal emotions or experience (as Lennon's songs usually did). That's not a criticism, just an observation; there are few songwriters that can do that as well as McCartney, and "Paperback Writer" was a superb trailblazer in that field. - Richie Unterberger

Eleanor Rigby

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Eleanor Rigby" was the most serious-minded song that the Beatles ever released when it first appeared in mid-1966, as part of a double-A-side with "Yellow Submarine." The Beatles had only just begun to write and sing songs that were not about love, with "Nowhere Man" and "Paperback Writer." "Eleanor Rigby" was different yet from those two predecessors - it was not only not about love, but was written entirely in the third person. What's more, it was a first in that the Beatles themselves did not play any instruments on the recording, which was played by a double string quartet of session musicians. Writing-wise, it was principally the work of Paul McCartney, who gave the piece one of his most outstanding sad melodies. In the main the lyrics were the sketch of lonely spinster Eleanor Rigby, although another lonely elderly figure, Father McKenzie, also has a prominent role. In a broader sense, the Beatles could be commenting here on the alienation of people in the modern world as a whole, with a pessimism that is rare in a Beatles track (and rarer still in a McCartney-dominated one). What are these characters doing their small tasks for, and what is the point: those are the questions asked by the song, albeit in an understated tone. Pessimism about the worth of organized religion is implied in the desolate portrait of Father McKenzie and the finality of the phrase "no one was saved." Far more controversial a critique of organized religion, when you think about it, than John Lennon's famous statement of the period that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus (which landed him in a great deal of trouble). It was most unusual, then and now, in such a youth-oriented medium as rock for a group to be singing about the neglected concerns and fates of the elderly, and was thus just one example of why the Beatles' appeal reached so far beyond the traditional rock audience. The desolation of Rigby and McKenzie's lives was brilliantly amplified by the arrangement, for which producer George Martin must take much credit. Its strident strings produce emphatic, dramatic beats in the manner of a Bernard Herrmann soundtrack ( Martin has admitted to being influenced by Herrmann's score for the Francois Truffaut film Fahrenheit 451 when devising "Eleanor Rigby"'s score), while the tempo variations subtly complement the lyric. Listen to how the strings increase in speed at the point where Father McKenzie is seen working, for instance. Other than Paul McCartney's lead vocal, the Beatles barely appear on the track at all, but they do add fine full harmonies to the chorus. As a double A-side, "Eleanor Rigby"/ "Yellow Submarine" made number one in the U.K., but in the U.S. (where the sides were charted separately), it only made number 11 to "Yellow Submarine"'s number two. It made for quite a daring pairing, actually: one side was the Beatles' most somber song to date, the other their wackiest. "Eleanor Rigby" is not an easy song to cover, due to its ambitious melody, varied rhythms, and the indelible imprint of Martin's arrangement, but somehow that has not kept a lot of people from trying, including soul singers Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles; Booker T. & the MG's (who did an instrumental soul version); jazz artists such as Joshua Redman; Dr. West's Medicine Show & Junk Band (with Norman "Spirit in the Sky" Greenbaum), who did an instrumental jug band rendition with kazoo; folk-rock singer Richie Havens, who put it on his Mixed Bag album; and the Vanilla Fudge, who did a typically agonizing drawn-out heavy rock treatment in the late '60s. - Richie Unterberger

Yellow Submarine

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Yellow Submarine" was the Beatles' first children's song, and one of the few they ever did, as it turned out. However, it was not solely meant for or appreciated by kids; it was a number two hit (number one in the U.K.), although its flip side, "Eleanor Rigby," was about as popular. The tune was a charming, predominantly acoustic singalong, constructed - as were several Beatles songs from 1966 onward - as a story of sorts. Submarines are in reality quite cramped and militaristic vehicles, but if you have to be on a submarine, the Beatles' "Yellow Submarine" certainly seems like the most fun one to board. Their "Yellow Submarine" is not a warship, but more like a joyful mobile home roaming the seas, steered and captained by the Beatles, joined by many of their friends. Written largely by Paul McCartney with some uncredited help from folk-rock star Donovan on a few lines, sung by Ringo Starr, and recorded with the help of many actual Beatles friends singing the chorus and adding sound effects, it was a true team effort. "Yellow Submarine," for all its popularity, is one of the Beatles' tracks that generates the most share of negative criticism, primarily from writers who found its gentle kid-friendly ambience too tame and corny, and not allied strongly enough with confrontational rock & roll ethos. The Beatles were not, however, trying to create a storming rocker with "Yellow Submarine," nor even to particularly express a deep and meaningful personal point of view. They were trying to make a fun song for kids and others to sing, and they succeeded mightily in doing so. In spite of Starr's typically doleful vocal, it's an exceptionally good-spirited track, one that makes the listener (most listeners, anyway) wish they could join the party onboard. The Beatles make this track a lot more interesting than it could have been in numerous ways. First, although it starts off like a sea shantie dirge, it quickly glides into a faster tempo, mimicking the increase of a submarine's speed as the journey gets underway. There are also the delightful sound effects of an actual onboard party, sounds of ship bells and waves, John Lennon's silly imitation of a boat commander, the brief instrumental burst of Salvation Army horns (right after the line "the band begins to play"), and the final rousing singalong choruses, in which the Beatles were joined by wives, friends, and producer George Martin. And was it just possible that some of the song's colorful images - the sea of green, and the yellow submarine itself - were psychedelically inspired? There are few more well-known Beatles songs than "Yellow Submarine," as it's the one Beatles composition most likely to be first learned by a young child. As if a chart-topping single wasn't enough to popularize it, it became more firmly embedded as a standard via the Yellow Submarine cartoon film, for which it served both as a theme song and as part of the movie's principal premise. - Richie Unterberger

The Beatles

Revolver

1966

Capitol

There has never been any lack of debate over which album is the original progressive rock release - the grandfather of the genre, the one that started it all - and that debate continuously recurs in fan magazines and on internet message boards, as any reader of this review will probably already know well. Most typically, prog rock enthusiasts rattle off a few choice titles: In the Court of the Crimson King, Days of Future Passed, something from the early Zappa, something from The Nice, etc. Just as often, though, and just as interestingly, there is a swelter of discussion with regard to the prototypes out of which even the first prog album emerged: the predecessors whose music hinted at the extravagant and often bombastic developments to come and whose success - commercial and aesthetic - widened the road for the passage of the later behemoths of classical rock. Commonly, the discussion about prog prototype albums involves a decent variety of artists and recordings - The Who, with its naive but powerful Tommy; the chaos and whimsy of Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd; S.F. Sorrow; perhaps Pet Sounds - and this variety at the least points out the abundance of influences which did eventually coalesce into the (admittedly tenuous) category of progressive rock music. However, there is one album that, more than any other, heralded an era of high musical experimentation and the incorporation of non-standard pop elements, and that album - the prototype for the art/classical/progressive rock of the late '60s and most of the '70s - is none other than Revolver, the Beatles' 1966 release.

One could not go so far as to label this album a bona fide entry into the progressive rock canon: that claim is extreme. But within Revolver - an absolute contender for the title "Greatest Album of the Rock and Roll Era" - are the seeds out of which will eventually grow the strong, sprawling vines of progressive rock composition and virtuosity.

The album opens with "Taxman", and The Beatles are already deconstructing Fab Four past. The song is a George Harrison classic and the movement away from "She Loves You" and "I Want to Hold Your Hand" is obvious enough, but as well, "Taxman" indicates the maturity of Lennon and McCartney, who step to the rear of the stage and let another Beatle bask in the limelight. Ironically, though, once to the fore, George laments, complaining about the machinations of government, which rob him of his wealth: there is no love in this song - it is political protest, satire, and existential angst. The Beatles have grown savvy, and are unimpressed with the designs of the old order. There is no little girl to make the man feel the part: there is the brutality of human strife with its high-handed thievery and deceit. A song of awareness, in short, accented by McCartney's demonic, acid-thrust guitar solo - short and searing, like a blast of LSD realization forced upon the consciousness - with distinct Asian halftones promoting a new pop-rock epistemology. The Beatles, like Bob Dylan, teach the coming generation of pop minstrels a new vocabulary, one that can, when spoken, effect change in the mind and in the heart. Progressive rock will later attempt further lessons in morality and sheer humanity.

George introduces another motif into the album with "I Want to Tell You," a jaunty little hippy-bounce that nevertheless rides atop some waves of dissonance; George (and John) will continue to delve into the realm of discordant sounds, and The Beatles' exploration will make possible much of the strident, harsh emotion found in the progressive offerings of, for example, King Crimson and Van der Graaf Generator. Playtime is (mostly) over and The Beatles have become musicians, and even artists.

The Asian strain runs rampant through Revolver, and this foreshadows the adoption of world-music themes and instruments into popular music that will, by the end of the twentieth century, become somewhat trite. George gives us a fairly pure dose of classical Indian music in his "Love You To," aligned with the lyricism of LSD and Hindu insight:

Each day just goes so fast

I turn around, it's passed

You don't get time to hang a sign on me.

This track also shows us to the true use of the sitar, about which Rubber Soul's "Norwegian Wood" merely teases. McCartney's closing vocals on "I Want to Tell You" echo the Oriental tonality of "Taxman" - a slippery singing, fluid and irregular, hard to catch and hold. And John Lennon utilizes the extreme mysticism of Tibetan Buddhism in the lyrics for "Tomorrow Never Knows." The Beatles have evolved and have brought the world into themselves (perhaps in part because they, as recognizable superstars, could not readily go out into the world). Progressive rock will not shy away from any of this (e.g., Jethro Tull's Stand Up) and, because The Beatles were indeed the biggest band in the land, and because they - whether willingly or not - grew out of the moptop teenage cuteness into large experimentation, still financially potent, they made the later tangents and deviations of progressive rock possible.

It is primarily George Harrison and Paul McCartney who are concerned with Asian music on Revolver; John Lennon is more intrigued by the effort to convey the intensity of the acid experience, the prismatic swirl of nightmare and infinite horizons. Lennon's music is the boldest on Revolver, utilizing syncopation and odd time signatures, bizarre sound effects, distorted vocals, stinging guitar tones, and the poetry of lysergic inebriation. It is just this very boldness - such a thorough disruption of the early Beatles mythos and naive musical charm - that authorizes the future novel adventures of progressive rock.

Notably, John Lennon's music is mainly far from pleasant or uplifting on Revolver; his angst spills out into the world of white pop and rock, and the future progressive musicians will be perhaps even more willing to explore their subjective response to existence, be it sweet or sour. Lennon envisions death on "She Said She Said," with its hornet-buzz opening guitar, and on "Tomorrow Never Knows," derived from Buddhist instruction for passage into eternal oblivion. Elsewhere, Lennon revels in a stoned, lazy ease ("I'm Only Sleeping") and the convenience of an accessible pusher ("Doctor Robert"). Although the fantasy element of his lyricism is evident ("Yellow Submarine"), the acerbic John Lennon is climbing out of the chrysalis, and while the memory of simple rock 'n' roller Beatle John lingers ("And Your Bird Can Sing"), still, the new visionary John is avant-garde and bitter.

Paul McCartney's contributions to the album are seemingly straightforward and yet his inventiveness at songcraft is no less apparent, and maybe more evident in juxtaposition with John and George's acidy meanderings. Paul's pop dabbling is really nothing short of brilliant and certainly works well to highlight the congruity of experimentation and formalism in rock.

Paul wears an assortment of musical coats on Revolver. On "Eleanor Rigby" he is back as the chamber ensemble maestro, but instead of the bittersweet "Yesterday," the tune paints a bleak, barren picture of modern culture, with lonely souls littered about and helpless. The deep under-rumblings of the cello give the song a brown hue. Many bands following the Beatles will at some point turn to orchestration to bolster their music: again, the enormous popularity of the Beatles, leading into the cultural acceptance of their inventiveness, made the development and advance of progressive rock quite permissible. In "Got to Get You into My Life," a glowing affirmation of LSD insight and the attendant freedom, utilizes brassy horn charts to drive along the song's positive vibe. McCartney, more than the other Beatles, was willing to incorporate the instruments of the symphony and jazz to expand the possibilities of pop music; bands like Gentle Giant could and did exist because of Revolver.

Paul does not abandon his trademark cuteness or sharp melodic sense, or his romanticism. "For No One" warns of love's tendency to fade; "Here, There and Everywhere" highlights the thrill of love's first (and remaining) blush. And on "Good Day Sunshine," Paul throws back the shades and lets the warm morning light shine down. On Revolver, Paul makes each of his songs a stew, tossing in this, then that, with a quick stir - and the blend does taste quite nice. Progressive rock will not necessarily adopt a McCartneyesque pop sensibility but it will remain open to the infinite possibilities of musical form and structure (or their absence).

Revolver is decidedly not a progressive rock album. But it is the album that, even in its compressed style, legitimized the evolution of rock music out of three-minute ditties. With its incorporation of world music, non-Western philosophical and psychological notions, orchestration, electronic gadgetry, existential reflection, and an expanded idea of what territory does in fact belong to the rock musician, Revolver proved that risk-taking could mix with commercial viability in pop music, and that proof was indeed the start of the progressive rock period. - JS