|

|

|

01 |

A New Day Yesterday |

|

|

|

04:11 |

|

|

02 |

Jeffrey Goes To Leicester Square |

|

|

|

02:12 |

|

|

03 |

Bouree |

|

|

|

03:47 |

|

|

04 |

Back To The Family |

|

|

|

03:53 |

|

|

05 |

Look Into The Sun |

|

|

|

04:23 |

|

|

06 |

Nothing Is Easy |

|

|

|

04:26 |

|

|

07 |

Fat Man |

|

|

|

02:52 |

|

|

08 |

We Used To Know |

|

|

|

04:03 |

|

|

09 |

Reasons For Waiting |

|

|

|

04:07 |

|

|

10 |

For A Thousand Mothers |

|

|

|

04:21 |

|

|

11 |

One For John Gee (bonus track) |

|

|

|

02:06 |

|

|

12 |

Love Story (bonus track) |

|

|

|

03:06 |

|

|

13 |

Christmas Song (bonus track) |

|

|

|

03:06 |

|

|

|

| Country |

United Kingdom |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

Ian Anderson - Martin Barre - Glen Cornick - Clive Bunker

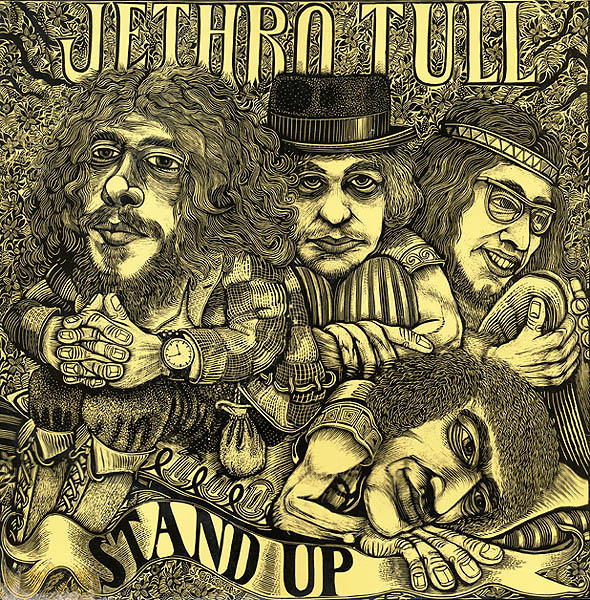

~ Stand Up ~

An introduction to "Stand Up"

In December 1968 after the release of 'This Was' and a visit to the BBC-studios, where Jethro Tull recorded a rendition of T-Bone Walker's 'Stormy Monday Blues', Mick Abrahams left the band. At this point Ian Anderson felt free to begin his songwriting in earnest, free of the blues tradition. 'A Christmas Song', 'Love Story' and 'Living In The Past' were the first examples of his song writing capabilities that show the emerging of his own style, using 'new' instruments like the mandolin. The popularity of the band increased, they had their first hits in the English Top 40 including the subsequent TV-appearances and continued touring extensively. Their first two gigs abroad took place in Stockholm, 9 & 10 January early 1969, where they opened for Jimi Hendrix. Three months of touring the US followed: the first one of many to follow. Tull opened for great bands like Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, Blood, Sweat & Tears a.o. In this period Ian wrote the songs for what would become the new album 'Stand Up'. Recording sessions started in April 1969. The album was released on August 1 and is now by many fans considered to be the first real Tull-album. It became an immediate success in the Uk and the US and lateron in other countries as well.

'Stand Up' contains ten songs, all written in a different style, a feature that is present on most Tull-albums. But there are more: the use of unconvential instruments such as the balalaika, mandolin, hammond organ, strings and - of course - Ian's characteristic flute playing. Another feature is the sequence of the songs: rock songs alternate with acoustic pieces. (We will see on later albums how this alternation is applied within the songs as well).

The flute has become the main instrument on this album, playing both a solo and a supporting role as well. Martin Barre - the new lead guitarist - adds with his versatility an extra quality to the album. When we look at the lyrics, they still are quite plain, like on 'This Was' most of them being love songs, but the poetic element and the imagination of feelings in most of them are striking. Anderson nowadays considers the songs as naieve and too self-centered, maybe because some of the songs on this album (and on 'Benefit' for that matter) reflect the difficult relationship he had with his parents as a teen.

Though the band on this album moves away from the straitjacket of the blues idiom, it still has a very bluesy atmosphere in songs like 'A New Day Yesterday', 'Back To The Family', 'Nothing Is Easy' and 'For A Thousand Mothers'. 'Stand Up' and the next album 'Benefit' show the transition from Jethro Tull as a blues band to a band that is about to set it's own standards when it comes to form of music and contents/subjects of lyrics.

Annotations

A New Day Yesterday

is the opening song of the album. A sturdy blues song, and one of the few that - though revamped - is still played during Tull-concerts. In it the narrator laments the impossibility of a relation because of obligations he has elsewhere:

"Oh I want to see you soon but I wonder how. (...)

Oh I had to leave today just when I thought I'd found you."

Jeffrey Goes To Leicester Square

The second song on the album refers, like 'A Song For Jeffrey' to Jeffrey Hammond, who joined Jethro Tull in late 1970 as bass player. This Jeffrey will turn up once more on the Benefit-album in the song 'For Michael Collins, Jeffrey And Me'.

Jeffrey was a very close friend of Ian. They had known each other since their school days and Jeffrey played several "pre-Tull" bands from 1963 to 1967.

* Jan Voorbij

"Leicester Square" is one of the cultural places in London with many theaters, cinema's and artist-pubs.

Leicester Square is a major place for entertainers of any sort to "strut their stuff"; you will find mimes, jugglers, musicians, and many more "street artists" of all sorts at work there. Musicians and other performers commonly set up, put out a hat or an open guitar case for donations, and go for it, both as solo artists and as groups. Active participation from the crowd of onlookers is often encouraged (providing they have something to offer; it's not amateur nite) and it is certainly a must-visit place for first-time (and any-time) visitors to London. The best time to go is week nights, esp. between 5:00pm and midnight. Most of the best performers have gigs on weekends.

* Patrick Marks

Bouree

Ask people "Do you know Jethro Tull?" and they will very likely answer: "Yes, they had a hit with Bouree." This piece of music was inspired by a lute piece composed by Johann Sebastian Bach. 'Bouree' does not only show Ian's improvisational talents on flute, but also brings Glenn Cornick's firm bass playing to the fore. It consists of three parts: the classic Bach theme, an improvisational part featuring flute and bass, and a reprise of the theme now played by two flutes.

What is the origin of the well-known and very successful Tull-hit 'Bouree'? After some research I came up with the following.

Ian Anderson's Bouree is indeed an adaptation of a Johann Sebastian Bach Bourree. The original version by Bach can be found as the fifth movement of the Suite in E minor for Lute (BWV 996). A suite is a popular 17th and 18th century musical form consisting of a series of dances. Most of the time a suite consists of four dance-forms: the Allemande (originated in Germany), the Courante (originated in France), the Sarabande (originated in Spain) and the Gigue (jig) (originated in England). Other dance forms were the Minuet, the Gavotte, the Polonaise, the Bourree, and many others.

The Suite in E minor, where Jethro Tull's Bouree can be found, is the earliest work that Bach composed for the lute. It is nick-named "Aufs Lautenwercke" (From works for the Lute). It dates from the middle of Bach's Weimar period (1708-1717). Bach did not compose many works for the lute and occasionally, in Bach's own time, those works were performed on the lute/harpsichord, a hybrid instrument in whose construction Bach had assisted. Now something more about the bourree. The correct spelling is 'Bourree' with an 'accent aigu' on the first e.

Here is an exceprt from 'The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians' (London, MacMillan, 1980, ISBN 0-333-23111-2.'; Vol. 3; pages 116-117). Article by Meredith Ellis Little.

"Bourree (Fr.; It. borea; Eng. boree, borry).

A French folkdance, court dance and instrumental form, which flourished form the mid-17th century until the mid-18th. As a folkdance it had many varieties, and dances called bourree are still known in various parts of France; in Berry, Languedoc, Bourbonnais and Cantal the bourree is a duple-metre dance, while in Limousin and the Auvergne it is commonly in triple metre. Many historians, including Rousseau (1768), believed that the bourree originated in the Auvergne as the characteristic BRANLE of that region, but others have suggested that Italian and Spanish influences played a part in its development. It is not certain if there is a specific relationship between the duple French folkdance and the court bourree.

Specific information on the bourree as a court dance is available only for the 18th century, whence at least 24 choreographies entitled bourree are extant, both for social dancing and for theatrical use. The bourree was a fast duple-metre courtship dance, with a mood described variously as 'gay' (Rousseau 1768) and 'content and self-composed' (Matheson, 1739). The step pattern common to all bourrees, which also occurred in other French court dances, was the 'pas de bourree' (Bourree step). It consists of a 'demi-coupe' (half-cut), a 'plie' (bend) followed by an 'eleve' (rise on to the foot making the next step), a plain step, and a small gentle leap. These three steps occurred with the first three crotchets of a bar, whether in the duple metre of a bourree or the triple metre of a sarabande, where the 'pas de bourree' was also used.

If the small leap were replaced by a plain step, the pattern resulting was called a 'fleuret'. The 'pas de bourree' preceded the 'fleuret' historically, and is somewhat more difficult to execute; by the early 18th century, however the two steps seem to have been used interchangeably, according to the dancer's ability. The bourree as a social dance was a mixture of 'fleurets', 'pas de bourrees', leaps, hops, and the 'tems de courante' (gesture consisting of a bend, rise and slide at places of repose. The stylized bourree flourished as an instrumental form from the early 17th century. Praetorius' "Terpsichore" (1612) included a few examples, all with quite simple phrasing and a homophonic texture. The Kassel Manuscript (ed. J. Ecorcheville, "Vingt suites d'orchestre", 1906/R1970) also contains a number of bourrees, often placed as the second dance in a suite. As the order of dances in a suite became more conventionalized in the familiar allemande-courante-sarabande group, the bourree continued to be included fairly often, coming after the sarabande with other less serious dances like the minuet and the gavotte. In that position it was included in orchestral suites by J.F.C. Fisher, Johann Krieger, Georg Muffat and Bach."

* Erik Arfeuille

Back To The Family

The song is about the double feeling in regard to the life the narrator lives. On the one hand he is fed up with the stressful life he lives, leaving him no peace of mind:

"Living this life has its problems,

so I think that I'll give it a break".

It makes him long for rest in the seclusion of family life:

"where no one can ring me at all".

On the other hand, once he chooses to do so, he gets bored with what he finds there, especially the dullness and recognizes what made him leave in the first place:

"Master's in the counting house counting all his money.

Sister's sitting by the mirror she thinks her hair looks funny".

It makes him wonder why he came back:

"And here I am thinking to myself just wond'ring what things to do."

To his own surprise he starts longing back for the tough life in the city:

"I think I enjoyed all my problems

Where didn't I get nothing for free."

and decides to go back as

"doing nothing is bothering me" and "

There's more fun away from the family

get some action when I pour into town".

But from the moment he gets there, everything he ran from starts all over again:

"Phone keeps ringing all day long, I got no time for thinking.

And every day has the same old way of giving me to much to do."

Does this song refer to Jethro Tull's heavily touring in 1969, when they performed in many US-cities, and the pressure of writing in the mean time a set of new songs to record when back home? And the constant tension caused by the frequent illness of the band members and tour proceeds that did not cover expenses? Clive Bunker noted that Ian quickly became dissillusioned with life on the road. He felt the constant pressure of being the singer, songwriter, frontman and leader of the band. There are more explicit references regarding this matter on the Benefit album, as we will see.

* Jan Voorbij

Fat Man

In the humorous song Fat Man, Ian is merely saying that he wouldn't like to be a fat man. He is glad that he is thin, and doesn' t have to put up with the ridicule and harassment that overweight individuals often go through in life. The verse "Too much to carry around with you" can either be interpreted as pertaining to the "baggage" of repeated verbal abuse upon an overweight person's consciousness, or to the literal extra weight that overweight people have to carry around with them. The verse "no chance of finding a woman who will love you in the morning and all the night time too" means that, though overweight men can find a woman of their own, their wives won' t want to make love to them. They would be married because of their love of each other' s personalities, not their physical attributes. Therefore, she would "love" him in the morning, but not "all the night time too." Ian says that he could not have the patience to ignore all of the ridicule that overweight people receive if he were fat: "Hate to admit to myself half my problems came from being fat" is saying that, as an overweight person, the ridicule and shame that you are subject to for looking the way you do is brought upon by yourself. Your own laziness to exercise, as well as the lack of control of your own appetite are the causes of your misfortune. Jokingly, Ian says that he "won' t waste his time feeling sorry for him, I've seen the other side to being thin." The only advantage to being overweight is that you would roll down a mountain faster than a thin person, which isn' t a very good consolation for the emotional torment that many overweight individuals go through, hence it being a joke.

* Ryan Tolnay

This was written as a way to get back at Mick Abrahams after his departure from Tull in January 1969. It's pretty self-explanatory.

* Julie Hankinson

We Used To Know

For decades I have assumed this song to be about looking back at a relationship that came to an end. It looks like a "sorry song" in which the narrator advises his former loved one to cherish the value of their relationship. And perhaps it is.

However, since I read parts of Brian Rabey's yet unpublished book "It's For You! The Magic And Musical Mayhem Of Jethro Tull", I tend to take a different view on this song. In chapter 2 "Jethro Tull christened" I found two quotes that suggest that the song is about the last months of The John Evan Smash, just before they became Jethro Tull. It refers to the period October 1967 - February 1968. Mick Abrahams had just joined The John Evan Smash, which in those days was a seven piece soul band in the process of transforming into a blues band. They wanted to move to London to "raid" the clubs and pubs from there. Since Mick lived in Luton - not far from London - the band moved to this place. But within three days Barrie Barlow, John Evans and the sax players went back to Blackpool. It became clear to them that they wouldn't earn enough money to cater for the needs of 7 people. So the band now consisted of Anderson, Abrahams and Cornick, and Bunker took the vacant drummer's seat. (In his book Rabey describes this process by citing Cornick, Evans and Anderson).

The John Evan Band changed their name to The John Evan Smash when they were picked for the Granada talent show "Firsttimers". This picture was taken on May 3, 1967, in front of the Granada Television studio in Manchester. The television show was broadcasted on May 24 that year. A few months later, in September, the band would make their first recordings with Derek Lawrence. After that, in October the big split took place, and when Mick Abrahams and Clive Bunker joined the John Evan Smash turned into a blues band: the embryonic Jethro Tull. From left to right: Neil Smith (guitar) , Ian Anderson (vocals, harmonica, no flute yet!), Neil Valentine (tenor sax), John Evans (hammond organ), Barrie Barlow (drums), Tony Wilkinson (baritone sax) and Glen Cornick (bass).

Now here is the first quote that suggests "We Used To Know" is about this period in the band's history and the above mentioned split-up. Rabey quotes Glenn Cornick who consulted his diary about those days (I added the applicable lines from the lyrics to that song - JV):

"Luton is also where Clive as well as Mick came from. Ian and I were living in apartments that were just too horrendous. I lived downstairs and he lived upstairs. Luton and Dunstable are doubled towns - Luton being the lower class section and Dunstable the upper class section. Ian and I lived in Luton probably the worst living conditions I ever went through in my life, but we had to live somewhere. I remember we used to share a can of irish stew everyday. The song "We Used To Know" from "Stand up" is about this period. You know the line: "Every day shilling spent"? In England, at that time, your gas supply was on a meter and you used to put coins in it. You'd be in the middle of heating up your Irish stew and the gas would go out, because your money had run out and, hopefully, you would have another coin to get it going again or you'd end up with cold Irish stew. We used shillings and that's "Every day shilling spent" ("Remember mornings, shillings spent").

The second quote is from the same chapter of Rabey's book. Anderson remembers the Luton period. After the coins and meters Glen tells us about in the above quote, he continues: "I ended up being very cold. ("Nights of winter turn me cold, fears of dying, getting old" and possibly "... shillings spent, made no sense to leave the bed"). Interestingly enough that was where I first put on the prized possession with which my father had furnished me upon my leaving home a few weeks before, which was a huge grey overcoat. I wore that on my first American tour. The reason I started wearing it was because I was very very cold. I was living in an attic room in an old house and I used to keep a glass of water by my bed at night and in the morning if I wanted a sip of water I had to break the ice on the top, it was that cold".

In that case this song is not by-gone love that is mourned but splitting up a band of friends that had worked so hard for a long period together in the hope to make it, living their harsh life of touring all over England, playing 6 or 7 days a week without even coming near to breaking through.

By the time "Stand Up" was released, the band had finally arrived in Europe and was making its way through the USA. In this songs it looks as if the narrator very well realises what he and the band went through before their breakthrough: "I think about the bad old days we used to know" and "The bad old days they came and went giving way to fruitful years". Their success emerged from working hard and consistently on their music for years: "We ran the race and the race was won by running slowly".

The struggle for survival, the frequent change in the line-up of the band resulting in periods of desintegration and building up again, the constant search for new musical directions: it all comes to the fore in the third stanza:

"Could be soon we'll cease to sound,

slowly upstairs, faster down.

Then to revisit stony grounds,

we used to know."

There is even a possible reference to this period when the band constantly changed their name to be able to get re-booked at the same places again (losing their sax players on the way):

"Take what we can before the man says it's time to go".

The last verse is a farewell and a good luck wish to the old friends that left. He advises them not to look back in anger and not to forget the adventurous time they spent together, for it will eventually lead to new possibilities:

"Each to his own way, I'll go mine.

Best of luck in what you find.

But for your own sake remember times

we used to know".

* Jan Voorbij

For A Thousand Mothers

Several songs on the Stand-Up and Benefit albums reflect the difficult relation between Anderson and his parents during his adolescent years, esp. with his father: "Back To The Family", "For A Thousand Mothers", "Son", possibly "Sossity: You're A Woman", and the later recorded "Just Trying To Be" and "Wind Up".

Anderson doesn't like these two albums very much, considering them to be "too self-centered". In "For A Thousand Mothers" this difficult relationship comes clearly to the fore.

The song is - in the first stanza - written from the point of view of a young man who is determined in his choices for the furure and is starting to become successful ("saying I'm wrong, but I know I'm right"). In spite of the pressure from his parents and their unsollicited advises, he has chosen his own way of doing things:

"Did you hear father?"

Calling my name into the night.

Saying I'll never be what I am now.

Telling me I'll never find what I've already found".

The second stanza appears to be a conversation between the parents. Note that the "baby" mentioned in the first line refers to the "he"-person in the second. (Note: compare the song "She's leaving home" from the Beatles' Sgt. Peppers album; it has a similar emotional quality). The parents are aware of the young man's dreams and have to admit that they came true:

"Doing the things he's accustomed to do.

Which at one time it seemed like a dream now it's true". The closing lines are interesting from a psychological point of view: here our narrator is talking again and states that it was the resistance of his parents, their opposing to his ambitions and their disapproval that made him fight even harder to realise them, thus giving way to "fruitful years":

"And unknowing you made it all happen this way".

The title of the song and the verselines:

"It was they who were wrong,

and for them here's a song".

suggests that it is dedicated to all parents, who do not give their children the "room to move" and the "finding out for themselves", needed to develop themselves in the direction they choose. This theme reoccurs in the first part of "Thick As A Brick", where society is criticized for imposing its values onto the young generation, stiffling them. Ian experiences at home as well as those at the Blackpool Grammar School are reflected in the lyrics to that album.

* Jan Voorbij

I want to conclude this page with a personal note - the only one I intend to make on this site: I relate to 'Stand Up' in a special way. It was my first Tull-album (though I knew the band for almost a year already from listening to illegal radio stations where "This Was"was aired). I got it from my parents on my 17th birthday in October 1969.

In the few weeks that followed the album changed my taste for music dramatically. It moved me away from Beatles and Rolling Stones, Animals and Byrds, Hollies and Move, from the soul music and the middle-of-the-road music of this era, that I was then interested in so much. I turned to the blues and the American and British underground music and everything that we nowadays would call progressive rock. Beside Tull, my new favorites became Frank Zappa, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, Cream, Soft Machine, Coliseum, Pink Floyd, Neil Young, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Jimmy Hendrix - to name a few heroes. 'Stand up' also triggered my interest for jazz, ethnic and classical music.

It was not only that Tull from that moment on became a musical love for life: I also discovered music as a form of art, that like poetry and painting requires efforts from us, readers, listeners, spectators - containing a language that give word, image, sound, representation to personal experiences, feelings, worries, thoughts or whatever.

I got specially interested in lyrics, assuming like many of us young students in those days, that every song 'had something special to say, if one was only willing to look for it'. This coincided with literature classes I took for Dutch, English and French, evoking my love for poetry.

I then of course could not foresee, that this website eventually would sprout from this interest.......

* Jan Voorbij

Stand Up

Date of Release Sep 1969

The group's second album, with Ian Anderson (vocals, flute, acoustic guitars, keyboards, balalaika), Martin Barre (electric guitar, flute), Clive Bunker (drums), and Glen Cornick (bass), solidified their sound. There are still elements of blues present in their music, but except for the opening track, "A New Day Yesterday," it is far more muted than on their first album - new lead guitarist Martin Barre had few of the blues stylings that characterized Mick Abrahams' playing. Rather, the influence of English folk music manifests itself on several cuts, including "Jeffrey Goes to Leicester Square" and "Look Into the Sun." The instrumental "Bouree," which could've passed for an early Blood, Sweat & Tears track, became a favorite concert number, with an excellent solo bit featuring Cornick's bass, although at this point Anderson's flute playing on-stage needed a lot of work. As a story-song with opaque lyrics, jarring tempo changes, and loud electric passages juxtaposed with soft acoustic-textured sections, "Back to the Family" is an early forerunner to Thick As a Brick. Similarly, "Reasons for Waiting," with its mix of closely miked acoustic guitar and string orchestra, all hung around a hauntingly beautiful folk-based melody, pointed in the direction of that conceptual piece and its follow-up, A Passion Play. The only major flaw in this album is the mix, which divides the electric and acoustic instruments and fails to find a solid center, but even that has been fixed on recent CD editions. The original LP had a gatefold jacket that included a pop-up representation of the band that has been lost on all subsequent CD versions, except for the Mobile Fidelity audiophile release. In late 2001, Stand Up was re-released in a remastered edition with bonus tracks that boasted seriously improved sound. Anderson's singing comes off richer throughout, and the electric guitars on "Look Into the Sun" are very well-delineated in the mix, without any loss in the lyricism of the acoustic backing; the rhythm section on "Nothing Is Easy" has more presence, Bunker's drums and high-hat playing sounding much closer and sharper; the mandolin on "Fat Man" is practically in your lap; you can hear the action on the acoustic guitar on "Reasons for Waiting," even in the orchestrated passages; and the band sounds like it's in the room with you pounding away on "For a Thousand Mothers." Among the bonus tracks, recorded at around the same time, "Living in the Past," "Driving Song," and "Sweet Dreams" all have a richness and resonance that was implied but never heard before. - Bruce Eder

Ian Anderson - Guitar (Acoustic), Flute, Guitar, Harmonica, Mandolin, Piano, Balalaika, Organ (Hammond), Vocals, Singer, Producer, Mouth Organ

Martin Barre - Flute, Guitar, Guitar (Electric)

Clive Bunker - Percussion, Drums

Glen Cornick - Bass, Guitar (Bass)

Andy Johns - Engineer

David Palmer - Synthesizer, Keyboards, Saxophone, String Arrangements, String Conductor

John Williams - Cover Art

Terry Jones - Producer

Jethro Tull - Stand Up

Released: 1969/2001

Label: Chrysalis - Capitol

Cat. No.: 35458

Total Time: 49:34

Reviewed by: Keith "Muzikman" Hannaleck, July 2002

Stand Up was Jethro Tull second release. Things were a bit toned down compared to the previous release, This Was. Martin Barre was introduced as the new lead guitarist. Barre's style was totally different than Mick Abrahams, and he wasn't allowed to really cut loose until the next album. Because of this radical change the sound of the group took an entirely different direction. This would be the most important transformation that they would make and it would subsequently change their fortunes forever. The folk aspects of their sound took precedence this time out, and although Martin Barre's guitar playing was often restrained, with the exception of "Nothing Is Easy," he was firmly establishing himself in the group. Gone was the prevailing blues authority and ushered in was the folk, classical, and ethnic influences with jazz and blues around the periphery of the core that was to reach its peak on the next album. They were exploring every aspect of their framework more distinctly on this recording session. Ian Anderson was in full bloom exploring all of his interest.

"Fat Man," one the best songs they ever made, had strong Middle-Eastern influences, and that was to be explored further down the road as well. "Bourиe" was a lovely instrumental piece, it featured Ian Anderson's flute in a decidedly classical light. The song conjured images of a ride in a horse drawn carriage along an old country road in the English countryside. The four bonus tracks are a hint of what the third release would sound like and provided an enlightening look into the tremendously successful future of Jethro Tull.

More about Stand Up:

Track Listing: A New Day Yesterday (4:11) / Jeffrey Goes To Leicester Square (2:12) / Bouree (3:47) / Back To The Family (3:53) / Look Into The Sun (4:23) / Nothing Is Easy (4:26) / Fat Man (2:52) / We Used To Know (4:03) / Reasons For Waiting (4:07) / For A Thousand Mothers (4:21) / Bonus Tracks: Living In The Past (3:23) / Driving Song (2:44) / Sweet Dream (4:05) / 17 (3:07)

Musicians:

Ian Anderson - glute, guitar, harmonica, piano, horn, vocals, mouth organ

Martin Barre - flute, electric guitar

Clive Bunker - drums, hooter

Glen Cornick - bass

Jethro Tull - Stand Up (+Bonus)

Country of Origin: UK

Format: CD

Record Label: Chrysalis Records Ltd.

Catalogue #: 535 4582

Year of Release: 1969/2001

Time: 70:05

Info: J-Tull.com Official Site

Samples: Jethro Tull Official Site

Tracklist: A New Day Yesterday (4:11), Jeffrey Goes to Leicester Square (2:12), Bouree (3:47), Back to the Family (3:53), Look into the Sun (4:23), Nothing Is Easy (4:26), Fat Man (2:52), We Used to Know (4:03), Reasons for Waiting (4:07), For a Thousand Mothers (4:21), Living in the Past* (3:23), Driving Song* (2:44), Sweet Dream* (4:05), 17* (3:07)

The first three Jethro Tull albums have recently been remastered and released with extra bonus tracks and new CD inlays which include a page adapted from the original record sleeve, plus another short narrative by Ian Anderson reminiscing about the history of each album.

Following the departure of lead guitarist Mick Abrahams (who went on to form Blodwyn Pig), Jethro Tull faced recording their 'difficult' second album with a new guitarist (Martin Barre). The result is Stand Up - the first step in moving from the more traditional blues style of This Was towards the unique progressive sound which served them so well throughout the seventies. This album is still heavily blues-influenced, but Ian Anderson's writing talent was starting to blossom, and there are some real gems in this collection, many of which are still regulars in the band's live set.

A New Day Yesterday starts the collection with the most 'bluesy' of the songs here. Glen Cornick's bass riff pushes the whole thing along at a good pace, whilst Clive Bunker's tumbling drums keep the track from becoming yet another blues dirge. About halfway through the track, we have a short guitar solo as a taster of what the future holds for the new guitarist, then a longer flute solo. A good blues song, then, but not a great Tull song - it's as if they're saying "Right, that should keep the blues fans happy, now let's get down to the new stuff..."

There is a much lighter tone for Jeffrey Goes To Leicester Square - bongos, gentle guitars and flute doodlings are the order of the day here. Short at just over 2 minutes long, this is probably most memorable for Anderson's pronunciation of 'Leicester' as 'Leester' rather than 'Lester'.

Bouree is a true Tull classic. Based on a piece by Bach, this starts off with a simple bass/flute melody, then the drums kick in as the flute takes off - Anderson letting loose with the style which would become one of his trademarks - grunting and whooping into the flute in a way guaranteed to make classical flutists run and hide. A brief bass solo at the half-way point is then followed by a return to the quieter melody from the start, before a final flourish with the flute.

Back To The Family is a short tale of 'the grass is always greener' - it switches between a light chatty tempo as the narrator considers the benefits of being elsewhere (either at home with the family or off in the city) and a heavy drums/bass/distorted guitar section when he realises that he was better where he was before.

A gentle mood lasts throughout Look Into The Sun, which is backed by very subtle bass and acoustic guitars, with occasional jazz-style electric accents. Not a drum to be found. It conjures up images of hazy summer days in the sixties.

Nothing Is Easy starts with a breathless flute introduction leading to a up-beat blues number backed by echo-laden guitar phrases. A minute into the song, and Barre and Anderson are trading licks with each other, showing that the flute can be just as effective in a rock context as guitar in the right hands. Another verse then a short round of solos before the band slowly build into a crescendo at the end.

Fat Man is not exactly politically correct, but who can resist a line like "Roll us both down a mountain and I'm sure the Fat Man would win"? This is a bit like a camp-fire song - bongos, tambourine, mandolins and flute back the lyrics which describe the drawbacks of being over-weight. Perhaps not classic Tull, but it certainly shows the light-hearted side which is part of their charm - this song always makes me smile.

Hotel California comes next, well actually We Used To Know, but Tull toured the USA supported by the Eagles at some point after this album, and shortly thereafter their own money-spinner was released. Can you tell the difference? Well, the Tull song has a bitter-sweet lyric of remembering the 'bad old days', and it has a soaring flute/guitar instrumental which never fails to send shivers down my spine. It doesn't have a catchy chorus, though, but with two superb guitar solos, who needs it?

Reasons For Waiting is more upbeat in contrast. Jangling guitars and light organ pads back a simple love song, which occasionally picks up a string section and could quite happily form background music to a holiday advert.

For A Thousand Mothers is similar in tone to Back To The Family - quite an aggressive bass/drum backing and presented from the point of view of an angry narrator - telling his family that he succeeded despite their doubts. The track fades out over an insistent band instrumental with each instrument fighting for its place in the mix.

Living In The Past is the first of the four bonus tracks on this disc. Probably the nearest the band ever got to the top of the singles chart, and with a 5/4 time signature to boot! The value of these bonus tracks (apart from 17) is diminished somewhat by them being available already on the Living In The Past album, however, they do come from the same period as this album, so they're not completely out of place here. Although this was the song which introduced me to Tull (thanks to Midge Ure's cover version), I have never really been too keen on it. Despite the catchy tune (or perhaps because of it?) I have always found it to be a bit out of place in the repetoire - it doesn't seem to fit with either the heavy or the quirky acoustic sides of the band.

Driving Song is a fairly plodding blues number - not actually bad as such, but it felt like filler material on the Living In The Past album (which was a bit of a mixed bag anyway), and adds nothing to this disc apart from a sense of completeness, perhaps.

Sweet Dream is another track which never quite feels like Tull - more like something by The Damned, but it is still a fine song - I love the little acoustic guitar flourish before each chorus starts. Strings and brass sections join in before the song fades out.

17 has only been available on CD before on the excellent 20th Anniversary box set, so this is an opportunity for those who missed out on that set to pick up a copy of this track. This is almost a pop song - certainly more so than Living In The Past - and feels as though it is from a different era - it would probably fit comfortably on Too Old To Rock And Roll - Too Young To Die, or date back to the John Evan Band era. It changes the dynamics of the disc from the original album - now it finishes on an upbeat number, rather than the somewhat heavier For A Thousand Mothers. The song was edited for space to get it onto the box set, so it seems a missed opportunity that the same edited version is presented here, rather than the full track.

In summary, this has been carefully restored - the instrumentation is clear and crisp - certainly a vast improvement on my old tape copy (although I don't have the earlier CD edition to do a direct comparison). Anderson's vocal on most tracks is heavily effected and kept relatively far back in the mix - I think was was an issue with his own confidence in his voice on the earlier albums - but it gives the album a unique colour which draws the different songs together. This is an essential purchase for a Tull fan, and recommended if you like your prog with a touch of the blues. It's not a Tull classic in the same league as Aqualung, A Passion Play or Songs From The Wood, but was an important stage in the development of the band's style.

Conclusion: 7 out of 10

Jonathan Bisset

Stand Up

Tull's initial musical approach was torn between Mick Abrahams' blues vision and Ian Anderson's more unique approach. When Abrahams left, his replacement Martin Barre became the key player in Tull's move towards a more progressive style.

The recording sessions for this album started in April '69. One month later, the band scored their first U.K. hit with "Living In The Past," which charted at #3 (included in the remastered release).. Starting with "Stand Up," the band's use of dynamics, Celtic Folk, and classically-oriented tonal structures, along with Ian Anderson's flute playing and songwriting, became Jethro Tull's signature. Simply put, "Stand Up" was the genesis of Tull's sound and, not surprisingly, is one of Anderson's favorite Tull records.

Reflecting back, "Stand Up" seems an obvious career turn but at its release, the reality was Tull risked a great deal. The turn from the blue-orientated approach displeased important Tull radio and promoter connections.

"A New Day Yesterday" is almost a holdover from "This Was" with its blues-stylings while "Nothing is Easy," common in concert sets, is a blues-jazz fusion. "Bouree," a "cocktail jazz" (Ian's words) rework of a J.S. Bach classical piece, would become a Tull classic and an almost must for any concert set. Many Tull fans presume Far Eastern influences on the band's music begin with Anderson's solo album "Divinities." Yet, traces can be found in "Fat Man" (sometimes considered a jab at departed guitarist Mick Abrahams) and "Jeffrey Goes to Leicester Square," one of three Tull songs devoted to Ian's boyhood friend Jeffrey Hammond who would later join the band.

While hardly a "concept" album, lyrically the album devotes a lot to Anderson's relationship with his parents (a subject continued on "Benefit") and coping with new found pop stardom.

This was the first album to be filled with songs written and arranged by Ian Anderson, the band's first album to chart in the U.S. top 20, and their first album to hit #1 in the U.K. It hit #1 two days after its release and stayed there for eight weeks!

Released: 1969 Remastered 2001

Charts: 1 (U.K.), 20 (U.S.)

A New Day Yesterday

Jeffery Goes To Leicester Square

Bourree

Back To The Family

Look Into The Sun

Nothing Is Easy

Fat Man

We Used To Know

Reasons For Waiting

For A Thousand Mothers

Living in the Past*

Driving Song*

Sweet Dream*

17*

* track added to the 2001 remastering and not included on the original release.

The original gatefold album featured a "pop-up" insert of the band and is today one of the most sought after Tull collector pieces.

Ian found out that "Stand Up" had hit #1 in the U.K. from Joe Cocker while breakfasting on the U.S. tour.

Tull opened for Led Zeppelin, Blood, Sweat, and Tears, and Grand Funk Railroad during 1969

"We Used to Know" was the inspiration for what late '70's classic song?

The Eagles' "Hotel California" derived from Henley hearing the song while touring with Tull

Ian Anderson - flute, acoustic guitar, hammond organ, piano, mandolin, balalaika, mouth organ, vocals

Martin Barre - electric guitar, flute

Clive Bunker - percussion

Glenn Cornick - bass guitar

Stand Up

Chrysalis (CDP3210422)

UK 1969

Glen Cornick, bass guitar; Clive Bunker, drums, all manner of percussion; Martin Lancelot Barre,electric guitar, flute on Jeffrey Goes to Leicester Square and Reasons for Waiting; Ian Anderson, flute, accoustic guitar, hammond organ, piano, mandolin, balalaika, mouth organ, vocals

conrad

Jethro Tull's second album saw them move away from blues, with the exception of the opening track, towards a more diverse style. However, with the possible exception of "Bouree", there is little on this album that could really be considered ground breaking in any way. The big step forward on this album was Ian Anderson's song writing. The entire album is made up of Anderson compositions or arrangements, as was to become the norm, and most are of high quality. The style leaps from blues ("A New Day Yesterday") to Indian influenced ("Fat Man") to whistful ("Reasons for Waiting") to aggressive ("For a Thousand Mothers"). There is also more use made of accoustic instruments.

The highlight for most people will be "Bouree". This is one of the oft-played pieces by J.S.Bach with the melody played here on flute and given new life by the use of a skip-beat. The result is one of the most succesful arrangements of a classical piece for rock, mainly because the walking bassline already existed in the original version.

Of course, the other notable change for this album is the inclusion of Martin Barre to the post of guitarist. Martin Barre has always struck me as a serviceable, though rarely brilliant guitarist. He does, however, have a very good feel for the music of Ian Anderson and already on this album managed to become an integral part of Jethro Tull's style.

This album makes a significant advance in terms of quality for Jethro Tull and is often considered among their top six albums. It is a very good collection late sixties rock songs with a couple of accoustic and quirky pieces thrown in. A very worthwhile album, if not for the most part progressive.

2-9-03

Jethro Tull

Stand Up

1969

Chrysalis

In late 1969, amidst the peak of a British Blues outbreak that dominated the English club scene and BBC airwaves, Jethro Tull's ascending star could shine no more brightly. The band was riding a swelling wave of popularity in response both to its successful debut release, This Was, and its live appearances at the Marquee Club, the Sunbury Jazz & Blues Festival, and opening for Pink Floyd at a free show in London's Hyde Park. Tull's unique and peculiar mixture of raw blues, jazz motifs, pop sensibility, and folkish nuance attracted a diverse listening audience. Although the band had by this time lost guitarist Mick Abrahams and his blues-purist approach, still, it persevered, replacing Abrahams with the more-than-capable and somewhat more versatile skill of Martin Barre. Frontman Ian Anderson garnered considerable attention and musical press with his theatrical flutework and stage drama, and by the time Tull released its second recording, Stand Up - just after issuing "Living in the Past" (with its tricky, non-commercial 5/4 beat) to strong acclaim - the band was in high demand.

Stand Up, along with The Beatles' output from Rubber Soul through Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Moody Blues' Nights in White Satin, Pink Floyd's Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and perhaps The Who's Tommy, stands as one of the finest proto-progressive rock recordings ever made. The album isn't quite "prog" proper; Tull would have a few years yet before it could stretch out and produce art rock masterpieces in the order of Thick as a Brick and A Passion Play. However, all of the foundational elements of the early 1970s progressive rock boom are there, in Stand Up, and the present-day listener, in hindsight, can hear the prog-train starting down the tracks.

Of course, that is not to say Jethro Tull was totally inclined to abandon the blues at this juncture of its career. Rather, under Ian Anderson's guidance, Tull - with its tight rhythm section of Clive Bunker on drums and Glen Cornick on bass guitar - branched out into a variety of musical styles, with blues-based rock 'n' roll as its trunk. Stand Up offers several blues-oriented pieces, including "A New Day Yesterday" and "We Used to Know;" the recording quality of these tunes is thick and coffeehouse-smoky, but pleasantly so, and any fans of John Mayall, Peter Green and Fleetwood Mac, or Cream might find some enjoyment therein. As well, certain songs - "Back to the Family," for example, and "Nothing is Easy" - move into the driving heaviness of early Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin, as Tull establishes its capability with thundering riffs. Over the top of it all is Anderson's flute, an odd choice perhaps in a blues/hard rock context (and this was Mick Abraham's opinion also), but it tends to fit more often than not - the introduction to "Nothing is Easy" sets the pace and timbre of the song with acumen. Where the flute is inappropriate, Ian Anderson simply blows the harmonica. The Roland Kirk legacy in Ian's nascent flute style is obvious, as he mutters and exclaims during breath intake, but if anything, it's humorous to hear someone wear an influence so openly upon the sleeve.

The more memorable tunes of Stand Up are those in which Jethro Tull starts its transformation into a progressive rock innovator. "Jeffrey Goes to Leicester Square" begins with balalaika and tuned percussion and segues into a mock-Slavic folk melody resting upon well-played hand percussion, and gives out tentative hints of "Mother Goose" and "Wond'ring Aloud" from Aqualung. A second tune, "Fat Man," is similarly cast in a folk setting, this time the Middle East, and - despite the sheer cruelty of the lyrics and their offensively nasal delivery - the music is thrilling and enthusiastic. Obviously, Tull on Stand Up is playing within the hippy zeitgeist of the late '60s, and it is definitely riding along with Zeppelin and Traffic in terms of acoustic arrangement and musicianship, but the band introduces world music into its solid rock delivery expertly.

In "Bouree," a snippet from J.S. Bach nonetheless, Tull showcases its affinity for both classical music and jazz, and here, again, we see the band making headway toward the art rock period, incorporating diverse musical forms into popular tunecraft. Glen Cornick gets a share of the spotlight here with a nice solo incorporating bass chords.

"Reasons for Waiting" is the beginning of a long-standing trend in Tull's catalog: Anderson, with acoustic guitar, as some minstrel out of the legendary past. Here, he's backed by a string accompaniment, a cliche today but at the time a novel willingness to move rock music away from the twelve-bar blues.

Chrysalis Records (under the aegis of Capitol Records) has released remastered versions of Jethro Tull's first three albums, each with bonus tracks. Stand Up includes the aforementioned "Living in the Past," and "Sweet Dream," a brilliantly energetic composition using a very brash horn chart with a Spanish, conquistador feel, as well as two other tunes from the era. Generally, the remaster is a mild improvement over earlier CD releases; the mix is clean and listenable, and extremely well balanced, but there's no huge increase in sonic integrity. Regardless, this is an outstanding example of Tull's early musical finesse and power - really, Stand Up made Tull's career, along with "Living in the Past" - and a fine move forward for the band. It is remarkable indeed (and admirable) that, once hitting such a high-water mark, Tull continued to reinvent itself and expand musically, at least through Warchild (if not beyond). Fans of Tull's more progressive offerings, curious about the origins of such complex and intricate performances, might like to try Stand Up, and fans of late '60s-early '70s rock 'n' roll would definitely find much of interest in the album. For Jethro Tull, at the tail-end of 1969, more impressive music was yet to come, but Stand Up did not and does not fail to command attention. - JS

Jethro Tull - Stand Up

Member: Cyclothymic Mood 7/7/03

In late 1969, amidst the peak of a British Blues outbreak that dominated the English club scene and BBC airwaves, Jethro Tull's ascending star could shine no more brightly. The band was riding a swelling wave of popularity in response both to its successful debut release, This Was, and its live appearances at the Marquee Club, the Sunbury Jazz & Blues Festival, and opening for Pink Floyd at a free show in London's Hyde Park.

Tull's unique and peculiar mixture of raw blues, jazz motifs, pop sensibility, and folkish nuance attracted a diverse listening audience. Although the band had by this time lost guitarist Mick Abrahams and his blues-purist approach, still, it persevered, replacing Abrahams with the more-than-capable and somewhat more versatile skill of Martin Barre. Frontman Ian Anderson garnered considerable attention and musical press with his theatrical flutework and stage drama, and by the time Tull released its second recording, Stand Up just after issuing Living in the Past (with its tricky, non-commercial 5/4 beat) to strong acclaim, the band was in high demand.

Stand Up, along with The Beatles' output from Rubber Soul through Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Moody Blues' "Nights in White Satin", Pink Floyd's Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and perhaps The Who's Tommy, stands as one of the finest proto-progressive rock recordings ever made. The album isn't quite 'prog' proper; Tull would have a few years yet before it could stretch out and produce art rock masterpieces in the order of Thick as a Brick and A Passion Play. However, all of the foundational elements of the early 1970s progressive rock boom are there in Stand Up, and the present-day listener, in hindsight, can hear the prog-train starting down the tracks.

Of course, that is not to say Jethro Tull was totally inclined to abandon the blues at this juncture of its career. Rather, under Ian Anderson's guidance, Tull with its tight rhythm section of Clive Bunker on drums and Glen Cornick on bass guitar branched out into a variety of musical styles, with blues-based rock 'n' roll as its trunk. Stand Up offers several blues-oriented pieces, including "A New Day Yesterday" and "We Used to Know"; the recording quality of these tunes is thick and coffeehouse-smoky, but pleasantly so, and any fans of John Mayall, Peter Green and Fleetwood Mac, or Cream might find some enjoyment therein.

As well, certain songs, "Back to the Family", for example, and "Nothing is Easy" move into the driving heaviness of early Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin, as Tull establishes its capability with thundering riffs. Over the top of it all is Ian's flute, an odd choice perhaps in a blues/hard rock context (and this was Mick Abraham's opinion also), but it tends to fit more often than not. The introduction to "Nothing is Easy" sets the pace and timbre of the song with acumen. Where the flute is inappropriate, Ian Anderson simply blows the harmonica. The Roland Kirk legacy in Ian's nascent flute style is obvious, as he mutters and exclaims during breath intake, but if anything, it's humorous to hear someone wear an influence so openly upon the sleeve.

The more memorable tunes of Stand Up are those in which Jethro Tull starts its transformation into a progressive rock innovator. "Jeffrey Goes to Leicester Square" begins with balalaika and tuned percussion and segues into a mock-Slavic folk melody resting upon well-played hand percussion, and gives out tentative hints of "Mother Goose" and "Wond'ring Aloud" from Aqualung. A second tune, "Fat Man", is similarly cast in a folk setting, this time the Middle East, and, despite the sheer cruelty of the lyrics and their offensively nasal delivery, the music is thrilling and enthusiastic.

Obviously, Tull on Stand Up is playing within the hippy zeitgeist of the late '60s, and it is definitely riding along with Zeppelin and Traffic in terms of acoustic arrangement and musicianship, but the band introduces world music into its solid rock delivery expertly.

In "Bouree", a snippet from J.S. Bach nonetheless, Tull showcases its affinity for both classical music and jazz, and here, again, we see the band making headway toward the art rock period, incorporating diverse musical forms into popular tunecraft. Glen Cornick gets a share of the spotlight here with a nice solo incorporating bass chords.

"Reasons for Waiting" is the beginning of a long-standing trend in Tull's catalog: Ian, with acoustic guitar, as some minstrel out of the legendary past. Here, he's backed by a string accompaniment, a clichй today but at the time a novel willingness to move rock music out of and away from the twelve-bar blues.

Chrysalis Records (under the aegis of Capitol Records) has released remastered versions of Jethro Tull's first three albums, each with bonus tracks. Stand Up includes the aforementioned "Living in the Past", and "Sweet Dream", a brilliantly energetic composition using a very brash horn chart with a Spanish, conquistador feel, as well as two other tunes from the era. Generally, the remaster is a mild improvement over earlier CD releases; the mix is clean and listenable, and extremely well-balanced, but there's no huge increase in sonic integrity.

Regardless, this is an outstanding example of Tull's early musical finesse and power. Really Stand Up made Tull's career, along with "Living in the Past" ? and a fine move forward for the band. It is remarkable indeed (and admirable) that, once hitting such a high-water mark, Tull continued to reinvent itself and expand musically, at least through Warchild (if not beyond). Fans of Tull's more progressive offerings, curious about the origins of such complex and intricate performances, might like to try Stand Up, and fans of late '60s-early '70s rock 'n' roll would definitely find much of interest in the album. For Jethro Tull, at the tail-end of 1969, more impressive music was yet to come, but Stand Up did not and does not fail to command attention.

c2001 - 2003 Progressive Ears

All Rights Reserved