|

|

|

01 |

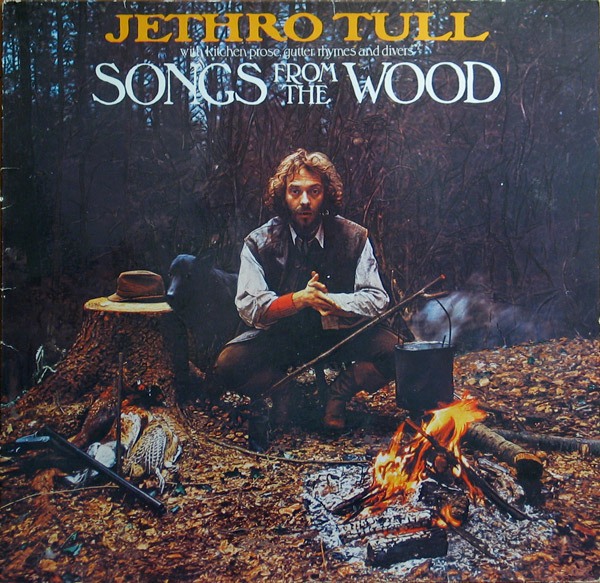

Songs From The Wood |

|

|

|

04:55 |

|

|

02 |

Jack-in-the-Green |

|

|

|

02:31 |

|

|

03 |

Cup of Wonder |

|

|

|

04:34 |

|

|

04 |

Hunting Girl |

|

|

|

05:13 |

|

|

05 |

Ring Out, Soltice Bells |

|

|

|

03:46 |

|

|

06 |

Velvet Green |

|

|

|

06:04 |

|

|

07 |

The Whistler |

|

|

|

03:31 |

|

|

08 |

Pibroch (Cap in Hand) |

|

|

|

08:37 |

|

|

09 |

Fire at Midnight |

|

|

|

02:27 |

|

|

|

| Studio |

Morgan Studios |

| Country |

United Kingdom |

| Cat. Number |

CDP 32 1132-2 |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

| Songwriter |

Ian Anderson |

| Producer |

Ian Anderson |

| Engineer |

Robin Black |

|

1998 re-issue by EMI / Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab

Ian Anderson: vocals, flute, acoustic guitar, mandolin, whistles

Martin Barre: electric guitar and lute

John Evans: piano, organs, and synthesisers

Barriemore Barlow: drums, marimba, glockenspiel, bells, nakers, and tabor

John Glascock: bass guitar and vocals

David Palmer: piano, synthesiser, and portative organ

All songs produced and written by Ian Anderson

Additional material by David Palmer and Martin Barre

Arrangements by Jethro Tull

(Jack-in-the-Green all instruments played by Ian Anderson)

Jethro Tull: Songs from the Wood

Mobile Fidelity (UDCD 734)

UK 1977

Sean McFee:

For their 1977 release Jethro Tull again changed their image, this time to a folkier, more acoustic sound. Longtime collaborator David Palmer joined as second keyboardist, although this is not key-heavy music. Rather, it is a lighter sound and not as overtly progressive as the earlier work. Anderson's flute-playing is in fine form, and his vocals are particularly good, as the story-teller in "Jack-in-the-Green" or as the protagonist of "The Whistler", in conveying an authenticity to the proceedings. Martin Barre sometimes adds a bit of a heavier edge, with a nice hard-edged riff in "Hunting Girl". He is not particularly aggressive on the album as a whole, though.

The album is captivating almost from beginning to end, although the two extended pieces ("Velvet Green" and "Cap in Hand") somewhat overstay their welcome. For the most part it is upbeat, charming and carefree, although Anderson himself thought it a bit twee, which might be a fair criticism. While I would caution people not to expect something in the vein of Thick as a Brick or A Passion Play, this is one of the most enjoyable Tull albums from where I sit.

Eric Porter:

This CD has so much going on in each song; the arrangements are probably the most complex of Tull's career: lots of flute, acoustic guitar, and a great band playing. The songs have a folk feel to them, but the other thing that really strikes me with this record is the bass playing. "Songs from the Wood" begins with a very folkish vocal arrangement and the song develops into a complex piece and sounds as progressive as anything Tull has done. "Jack in the Green" is another song that has a folk arrangement, based on a lot of acoustic guitar. "Cup of Wonder" is a straight ahead song with a folk feel with lots of acoustic guitar and flute. "Velvet Green" one of my all time faves. Very medieval sounding intro with harpsichords, flutes, recorders, great arrangement. I am an admitted Tull fan (I don't want to mislead anyone) but don't go by Tull standards such as "Locomotive Breath" or Aqualung, as this CD (and the subsequent Heavy Horses) are a departure from that classic sound. Anderson admittedly wrote this CD in celebration of the countryside, and though a folk feel runs through it, there is more than enough rock to keep you active. Also, this is not your singer /songwriter folk, as the arrangements reach orchestral heights. The combination works to perfection, every nuance of this record belongs right where it is. Not as heavy as many of their more popular songs and not as poppy either. This is what a Tull record should be, and nobody does it better.

Songs From The Wood ~

(1)

An introduction to

"Songs From The Wood"

Jethro Tull would close out the seventies with a trilogy of albums that would most eloquently and cohesively express Anderson's world-view. He would continue with these themes in later albums but these attempts would prove to be expansions or recapitulations of the ideas stated in these three works. It is in these albums that the urban/rural dichotomy comes to the fore and Celtic/pre-Christian ('pagan') myth and imagery, which had been used sparingly in the past, is used prominently.

Previous Tull albums have been generally cynical and quite trenchant with regards to modern society. With the album at hand, these elements are inverted. A largely celebratory mood is invoked with the lyrics in praise of nature and of past rural life. Previous albums portrayed modern life as being spirtually hollow and in decay while the current album portrays a way of life that Anderson sees as full of meaning with a sense of community and respect for nature. This environmental theme will be most prominent in the final album of the trilogy, Stormwatch. The first track 'Songs From the Wood' begins with the title track: "Let me bring you songs from the wood, To make you feel much better than you could know." These lines are sung in a madrigal-like acapella chorus. The narrator wants to show us "how the garden grows" and to bring us "love from the field." He urges us to "join the chorus if you can." He calls us to become a part of larger community pursuit of a greater good. Contrast this with the criticisms evident on Thick As a Brick. It would seem that Anderson is trying to construct a set of values that would be appropriate for society to pass onto its young. In an interview the following year, he would reveal how he has integrated some of the ideas on the album into his own life: " ... rather than spending his money on drugs, parties and cars, I would rather have something tangible at my disposal and also something I can feel a little bit responsible for. That's one thing money buys: the right to acquire responsibility for things or people or animals or whatever".

'Songs From The Wood' is ripe with folk instrumentation, but it is not folk music. There is electric guitar and rock drums but it is not rock music. It is a complex mixture of both these musics and more. Regarding the appropriation of English folk music Anderson has said, "It's more than a liking for the instrument. It's a response to the music - that droning quality - Celtic music. It's something special. One can't really pin down what. It has to be some kind of folk memory." It is also noteworthy that this musical break with their past involved the inclusion of 'additional material' by David Palmer and Martin Barre. This album was more of a group effort than past albums.

"Songs from the wood : the music and lyrics of Ian Anderson", John Benninghouse; adaptation Jan Voorbij.

As said before, on the albums 'Songs From the Wood',' Heavy Horses' and 'Stormwatch', Ian Anderson makes use of all kinds of references and images from English folk song, as Caswell states in his astute 1993 paper: "In fact the images are too numerous to be dealt with thoroughly here. However, with just a brief look, we can find that English folk song is a source of validation for religious and sexual rebellion. The matter-of-fact sexual attitude expressed on Songs From the Wood and Heavy Horses is in no contradiction with true English folk song. Stuart, in his Pagan Images in English Folk Song, explains that sex was considered quite natural and a worthy topic of song (59). Lloyd explains that in an agricultural society, all kinds of fertility are sacred--human, animal and plant. He goes on to say, "Nowhere does this intimate consonance with nature show clearer than in the erotic folk songs" (p, 197).

Particularly striking images arise from the rite of Beltane, or May Day: Stories abound of young men and women running amok in the woods on the eve before the first of May. Church officials condemned such practices, swearing that a full two-thirds of the maidens returned home "defiled" (Lloyd, 106-107). For the pre-Christian peasant, these were not defiling acts: The first of May was seed time, and after planting it was believed that the seeds should be assisted in their fertilization. The sexual energy of the most virile members of the community was required to ensure the success of the crops (Lloyd, 106). Young couples copulated in the furrows of the fields to assist the crops along as well (99). As a result of these pagan practices, sexual imagery involving fields and farms is abundant (200)."

"The sexual imagery on Songs From the Wood and Heavy Horses is full of such references. The main sexual songs on the album "Songs From The Wood" are "Velvet Green" and "Hunting Girl".(...). All songs involve love in the wide outdoors."

Annotations

Songs From The Wood

'Songs From the Wood' , the title track, begins with: "Let me bring you songs from the wood, To make you feel much better than you could know." These lines are sung in a madrigal-like acapella chorus. The narrator wants to show us "how the garden grows" and to bring us "love from the field." He urges us to "join the chorus if you can." He calls us to become a part of larger community pursuit of a greater good.

* Judson C.Caswell

"Galliards", or in french "gaillardes" are dance songs from the Renaissance era.

Obviously the title is in itself one of the most interestingly rich features of the song and of the album, since it is title for both. I think we ought to take into account the fact that the sentence can be understood in two (if not more than that, as is usual with Ian Anderson) different meanings, the first one being, of course, songs from the countryside in opposition to urban life. The wood here symbolises the old way of life, the rural one, when human beings were closer to nature and understood it better. Now they are destroying it, and the narrator wishes us to hear the voice of Nature singing in these songs from the Wood, telling us to come back to a better way of life in harmony with Nature.

Secondly, since the album reverts to such a folk kind of music, "from the wood" might mean "from wooden instruments", that is to say older ones than electric guitar and the kind. Of course electric guitar is present in the album, but I can think of no other album than Heavy Horses that has as old-flavoured music as Songs From the Wood, and the song in itself is a example of the mixing up of old i.e. traditional folk style and new style. The verseline "Let me bring you old things refined" is quite clear in this way, and "Dust you down from tip to toe" applies to us listeners, meaning that we need to get off ourselves the dust accumulated through generations of evolution in order to find back what is lying at the bottom of us, i.e. the older way of life. Hence the narrator says he wants to revitalise us because our current life is killing us: let me "... show you how the garden grows" is explicit: in our modern way of life we have so detached ourselves from Nature that we do not even know how plants and vegetables grow any more! We are only concerned with eating, without thinking what a marvellous process of creation has had to take place before we can have the said vegetables in our plates.

"Let me bring you love from the field" means for me "let me show you that Nature loves you, because you are her children," and "to heal the wound and still the pain" once again explicitly implies that our modern society and way of life endanger our health. "Life's long celebration's here" means that life is in Nature, not far from it, and that if we want to enjoy life again (Ian constantly implies that we do not, even though unconsciously, enjoy life in its western, modern, urban way) we have to come back to rural life.

"I am the wind to fill your sail / I am the cross to take your nail" imply two metaphors: in the first one the narrator says he will fill our sail with wind in order to help us sail towards better life, and the fact that he talks of a sail goes on well with his idea of the old ways of life being better: a boat with a sail does not pollute! In the second sentence Ian does no less than, I think, comparing himself with Christ, i.e. let me be the one to pay for your sins so that you can life happily. Finally, "A singer of these ageless times / With kitchen prose and gutter rhymes" apply to himself, so he positions himself as a kind of herald of these forgotten times when life was better, and he also implies that his discourse and songs are all but serious: kitchen, that is not very good prose, and rhymes from the gutter mean that we must not take things too seriously but rather revel in a simple but healthy way of life.

* Fred Sowa

Velvet Green

"is a wonderful pick-up song, sung by a amorous young man, asking his love to stay with him and "tell your mother that you walked all night on Velvet Green." The song presents sex on the open fields with a "silver stream that washes out the wild oat seed", and though "civilization is raging afar," the man still urges the woman, "But think not of that, my love, I'm tight against the seam. And I'm growing up to meet you down on Velvet Green."

Imagery in this song is reminiscent of images from an English folk song called "The Mower," in which the fair maid is unsatisfied with her beau. "I'll strive to sharp your scythe, so set it in my hand" says the maiden (Lloyd, 201). "Velvet Green" includes the line "Won't you have my company, yes take it in your hand."

As the first lines of the song imply, it is about living without a care in a rural way, so it sums up the whole message of the album. The Velvet Green of course refers to the green grass of Scotland, Ian's birthplace, but I think we can take it as a larger metaphor for Nature in general. "Walking on Velvet Green" would thus mean "following the green way, the green road of Nature," that is to say living in harmony with Nature. Of course it is about a sexual relationship between a country girl and a country man, but once again I think we should take this as a metaphor meaning that real, enjoyable and healthy life lies in a closer relationship with Nature (embodied in previous songs in the Green Man, Jack-in-the-Green, and here in the narrator) and the awareness that we ourselves are part of Nature.

"Won't you have my company, yes, take it in your hands.

Go down on velvet green, with a country man.

Who's a young girls fancy and an old maid's dream.

Tell your mother that you walked all night on velvet green.

One dusky half-hour's ride up to the north.

There lies your reputation and all that you're worth.

Where the scent of wild roses turns the milk to cream.

Tell your mother that you walked all night on velvet green.

And the long grass blows in the evening cool.

And August's rare delight may be April's fool.

But think not of that, my love, I'm tight against the seam.

And I'm growing up to meet you down on velvet green".

This whole stanza reminds me of Sweet Dream:

"You'll hear me calling in your sweet dream, Can't hear your daddy's warning cry. You're going back to be all the things you want to be While in sweet dreams you softly sigh. You hear my voice is calling to be mine again, Live the rest of your life in a day".

It is an invitation to forget about our education, which restrains us from enjoying life, and is embodied in both songs in the parents. The narrators appear as kinds of tempting characters, probably devils or incubuses in the parents' minds, but who in fact want only to show us the way to a better way of life. The line "Now I may tell you that it's love and not just lust / And if we live the lie, let's lie in trust" mean that the narrator does not only want to have sex with the girl in question, but really to be in love with her, i.e. on a more general level, the relationship with Nature must not be based on profit (using natural resources in a wild way that leads to Nature's destruction) but on real harmony and love.

The final verses "And the ragged dawn breaks on your battle scars. As you walk home cold and alone upon velvet green" add a touch of sadness, because the girl has to go back home alone, she can't stay with her nocturnal, dream-like lover, and we indeed have a feeling that everything was just a dream, that it never existed, but there is still the hope that, be it dream or reality, it will happen again the night after, and every other night.

There is a clear dichotomy between daytime and night-time in this song, the latter being the time when the girl's (our) dreams and fancies and most profound desires come true, and day-time being the time for the harsh reality of urban life. Ian will express the same idea in "Pussy Willow" a few years later: in fact the girl in "Velvet Green " and the one in "Pussy Willow" might be the same. We have to notice that night is predominant in the album "Songs From The Wood": "Velvet Green" and "Fire At Midnight" both depict scenes taking place during the night, whilst "Cup Of Wonder" begins with the opening line "May I make my fond excuses for the lateness of the hour", once again implying it is night-time. It seems that Ian wants to give night a very positive value, it being the time for feasting ("Cup Of Wonder,") love-making ("Velvet Green") or lovesong-writing ("Fire At Midnight")

* Fred Sowa

Hunting Girl

"says: "She took the simple man's downfall in hand; I raised the flag that she unfurled." "Hunting Girl" is another of his sex-in-the-fields songs. However, this is the story of an aristocratic lady who seduces a lowly field worker with wild and extravagant practices: "Boot leather flashing and spur-necks the size of my thumb. This high-born hunter had tastes as strange as they come. Unbridled passion: I took the bit in my teeth. Her standing over: me on my knees underneath." These playful allusions to sex bear strong resemblances in tone to many early folk songs, and Ian's stage gesturing can be related to folk sources as well. "Bawdiness and sexuality, loose talk, obscene gestures, priapic dance, are the starting points for many ceremonial dramas of springtime" (Lloyd, 106)." (...)

Apart from the fact that this is one of the most kinky songs Ian ever wrote, I would like to point out that the girl depicted in it is the perfect representation of the Celtic woman. Contrary to other civilisations, it seems from mythological, judicial and literary evidence that women had a very happier condition in Celtic societies in the Dark Ages (the period just preceding the Middle-Ages) than in any other. Celtic women were among other things renowned for their sexual freedom, because when they wanted a man they just went to him and made it clear that they were interested in having sex with him. The concept of sin was totally unknown to Celtic peoples before their conversion to Christianity, and a married woman could have an affair with another man practically in total impunity, and vice-versa. But a distinctive feature of mythological feminine Celtic characters is that they usually were depicted as "femmes fatales," and in the relationship between a man and a woman the dominant character was often the woman.

From thence sprung the concept of "amour courtois" or courtly love, which we find in medieval romances: the man is totally and in every respect devoted to the woman, obeying her every wish and whim. We find the same feature in the song: the lady is depicted as a "hunting girl," but what she hunts is in fact males! And when she makes it clear to the narrator that she wants sex, he just cannot refuse. Moreover, the supremacy of the woman is expressed in the position she adopts: "Her standing over / Me on my knees underneath."

Finally, interestingly enough the narrator calls her "the queen of all the pack" which reminds me of Queen Medbh (pronounced Maeve) of Irish Mythology: she was famous for her sexual appetites, and her total lack of scruples to sleep with someone else than her husband. (Fore more information about Celtic mythology or Celtic women, I recommend Jean Markale's books The Celts : Uncovering the Mythic and Historic Origins of Western Culture, and Woman of the Celts.

* Fred Sowa

Jack-In-The-Green

"This rejuvenation (of nature/life - jv) is clearer in 'Jack-In-The-Green' from Songs From the Wood. Jack, as presented in the song, is responsible for keeping the green alive over the winter and bringing it out again in spring. According to Stewart, Jack-In-The-Green is one of the many names by which Saint George is known. He is also called the Green Man, is associated with many fertility rites, including Beltane, and is responsible for returning leaf and life after winter. Ian Anderson applies this powerful healing spirit to a very modern question. Considering the environmental terrorisms of industrialization as a kind of winter, he asks:

"Jack do you never sleep? Does the green still run deep in your heart?

Or will these changing times, motorways, powerlines keep us apart?

Well I don't think so, I saw some grass growing through the pavements today."

This stanza illustrates two things: 1) that there is hope for modern civilization and 2) this hope lies in reaching back to tradition for a different view of the man's relation to nature. This is a small precursor to the environmental concerns expressed later in the trilogy.

"Though the audiences of these songs and viewers of his shows may not recognize the specific historical references presented, that doesn't change the historical significance of the work (Lipsitz, 104). It is likely that Ian Anderson doesn't fully understand the images he refers to: for instance, his Jack-in-the-Green, according to a concert clip off Bursting Out, is one of many little woodland sprites that cares for plants. The explanation is wrong, but the image serves the proper function nonetheless. "

This reflects Lloyd's idea of a folk-memory, through which connotations remain long after true meanings are lost (Lloyd, 96). Stewart would say that the strength of Ian's imagery lies in the unconscious appeal of the magical symbols, and that he has tapped into a source of racial consciousness and identity (Stewart, 13). Lipsitz says "all cultural expressions speak to both residual memories of the past and emergent hopes for the future" (13). Ian's utilization of old pagan imagery of fertility and rebirth are being put to work in the present to accomplish a sense of hopefulness. His agenda at last is not political, but spiritual, and he accomplishes a sense of tranquility and rightness for those who can empathize with his imagery. His goal: "Let me bring you Songs From the Wood, to make you feel much better than you could know."

"Conclusions: Now it is possible to compare where Ian Anderson is in 1978 to where he started in 1968, with Roland Kirk. Lipsitz identifies Kirk as a performer who is deriving his power from a sense of history. He explains that Roland Kirk presents an art that can be interpreted at many levels - an art that makes reference to the past through oblique and coded messages. These messages arise as eccentricities in Roland Kirk's music and stage presence (4). Ian Anderson strove to make that same kind of historical connection, and to have that connection be manifest in all of his works. He felt no sense of group-identity with the rock 'n roll culture of his times, so he searched elsewhere for his historical connections. With these connections he found a voice for emotional and critical expression. The imagery of English folk culture permeated his work and allowed him to evoke the past to accomplish his artistic goals."

* Judson C.Caswell (SCC, vol. 4, issue 32, December 1993) ; adaptation Jan Voorbij ;

Works Cited: 1. Anderson, Ian. "Trouser Press Magazine." Autodiscography, (Oct. 1982), 1-13.; 2. Densflow, Robin. "Rolling Stone." Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson Plans a Movie; He'll Play God, (11/8/73), 14 ; 3. Hardy, Phil and Dave Laing Ed. Encyclopedia of Rock, New York: Schirmer Books, 1987; 4. Lewis, Grover. "Rolling Stone." Hopping, Grimacing, Twitching, Gasping, Lurching, Rolling, Paradiddling, Flinging, Gnawing and Gibbering with Jethro Tull. (7/22/71), 24-27; 5. Lipsitz, George. Time Passages. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990 ; 6. Lloyd, A.L. Folk Song in England. New York: International Publishers, 1967 ; 7. Sims, Judith. "Rolling Stone." Tull on Top: Ian Anderson Speaks His Mind, (3/27/75), 12; 8. Stewart, Bob. Pagan Imagery in English Folksong. N.J.: Humanities Press Inc. 1977. 9. Torres, Ben Fong. "Rolling Stone." Jethro Tull and His Fabulous Tool, (4/19/69), 10.

The Greenman

The powerful foliate head of the Greenman is a symbol still seen today carved on mysterious stones, ancient churches and on Celtic artifacts. In Celtic folklore, he peers at us through the masks of Cernunnos the Wild stag-horned Lord of the Hunt, Herne the Hunter, the Green Knight of Arthurian legend, Jack-in-the-Green (...). He protects the forest and is the spirit of the land - and is still used todayas a good luck symbol for gardeners. His face, carved in golden oak, can also be seen in Windsor Castle, where it was restored after their disastrous fire.

* Artwork and information: courtesy of c Chris de Haan

Neil Thomason has a different opinion on the origins of Jack-In-The-Green and states: " 'Jack-In-The-Green' is an English character, as Ian acknowledged numerous times on stage. Some have argued here that the song relates to the Green Man. I'd disagree, but in any case, the Green Man is a figure of English, not Celtic folklore. Okay, there's some cross-over, but as generally understood, he's English."

* Neil Thomason (SCC vol.9 nr. 14)

Here are the two references to Jack-in-the-Green from J.G. Frazer's book 'The Golden Bough: a study in magic and religion' (abridged edition, Macmillan 1987): "In England the best-known example of these leaf-clad mummers is the Jack- in-the-Green, a chimney-sweeper who walks encased in a pyramidal framework of wickerwork, which is covered with holly and ivy, and surmounted by a crown of flowers and ribbons. Thus arrayed he dances on May Day at the head of a troop of chimney-sweeps, who collect pence [money] . . . . it is obvious that the leaf-clad person who is led about is equivalent to the May-tree, May-bough, or May-doll, which is carried from house to house by children begging. Both are representatives of the beneficent spirit of vegetation, whose visit to the house is recompensed by a present of money or food." (p. 129).

And: "In most of the personages who are thus slain in mimicry it is impossible not to recognise representatives of the tree-spirit or spirit of vegetation, as he is supposed to manifest himself in spring. The bark, leaves, and flowers in which the actors are dressed, and the season of the year at which they appear, show that they belong to the same class as the Grass King, King of the May, Jack- in-the-Green, and other representatives of the vernal spirit of vegetation . . . " (p. 299). All in all, this book is essential reading for information about pre-Christian rituals and folk-beliefs.

* Andrew Jackson

The "Greenman" is in various form carved into English Christian churches by stonemasons and woodcarvers, which purport to be forest-gods from England's pagan past. You can see some examples of Green Men on these sites:

"The search for the Green Man" and "The Green Man: variations on a theme". For more specific information, see "Who is the Green Man".

When I first visited your site I was immediately struck by the image of Ian Anderson as Green Man that you use as a repeated motif in your site.

* Harrison Sherwood

Cup Of Wonder

This song is a fairly explicit call for the listener to at least reconsider what tradition has to offer. The song calls back "those who ancient lines did lay". A ley line, in Celtic lore, is a line in the ground along which the energy of the earth flows. These lines were to connect sacred sites such as Stonehenge. After more Celtic images (standing stones, the Green Man, et al) the listener is asked to: "Question all as to their ways, and learn the secrets that they hold." This line perhaps sums up the message of the entire album better than any other. Other pagan/pre-Christian references include the line "Pass the cup of crimson wonder", which refers to Druidic human sacrifice. Peg Aloi interprets the lines "Join in black December's sadness, Lie in August's welcome corn." as referring to the pagan holidays of Yule and Lughnasa.

* "Songs from the wood : the music and lyrics of Ian Anderson", John Benninghouse; adaptation Jan Voorbij.

I was surprised by the interpretation of the "cup of crimson wonder" in Jethro Tull's imagery in Cup of Wonder. There are several reasons to believe the reference is to wine, not blood. For one, the song is an upbeat tune describing the revelries of Beltane. Beltane was a fire/fertility festival where the emphasis was on sexuality, not on sacrifice. Tradition included drinking, feasting and dancing. Second, the invocation of wine for visualizing "the green man" in the bipartite line: "Ask the green man where he comes from, ask the cup that fills with red." suggests that the cup is a source of ritualistic knowledge that imparts insights about life and visions of the supernatural.

Finally, while there are some who claim the Druids engaged in bloodletting as a sacrificial rite, most historians recognize the Roman claim of ritual immolation of prisoners, but remain doubtful of blood as a significant component of Druidic ritual life.

* Mark Davis

This has to be among the most brilliant of Anderson's many brilliant lines: "For the May Day is the great day, sung along the old straight track. And those who ancient lines did lay will heed the song that calls them back". (...)"Cup of Wonder" is about pagan and quasi-druidical rituals (or how we today imagine that they were, since nobody knows for sure.) "Beltane" is the name of an old pagan ceremony surviving as May Day (...). Here's why the couplet is so brilliant: First it contains a literary allusion: "The Old Straight Track" was a book published in 1925 by Alfred Watkins, an amateur archaeologist, about the lines of standing stones and other megalithic monuments in Britain and France. He believed that the alignments of the stones were evidence of, or channels for, some unknown power in the earth. Deliberately aligning buildings, furniture, etc. to correspond with these lines is a type of magic called geomancy(...). But even more amazing, the next line contains a TRIPLE pun. There are three ways of reading "those who ancient lines did lay": 1) "lay" means to put or set down; it refers to those who placed the stones in their alignments. 2) "ley line" is another term for the mystical lines of power that are said to be under the earth. This term was first used by Alfred Watkins. The origin of the word "ley" is vague, but may be from "lea" for a tract of open ground, or the Saxon word for a cleared glade. 3) "lines did lay" can also refer to to minstrels writing lays, a form of poetry (as in "The Lay of the Last Minstrel," by Tennyson). The term "lines" then refers to the lines of words that make up the lay. And we know that Ian is fond of the idea of minstrels; it makes just as much sense that the minstrels will "heed the song" as it does the original builders of the alignments. The man is a stone (!) genius.

* Ernest Adams (SCC vol. 9 nr. 4)

In the line "pass the word and pass the lady", lady is probably the sabbath-cake which many pagans referred to as "the Lady". Here is referred to witches sabbat, of which Beltane is one of eight. Cakes and ale (or wine) is the traditional sacrament. One would "pass the word" because coven meetings (where a group of witches would work magic together) were, after all, secret affairs.

* Jessica Alexander

Ring Out, Solstice Bells

This song is a dance to celebrate winter Solstice (mostly on the 22nd and sometimes on the 21st of December) and appeals to rejoice the lengthening of the days, c.q. the return of the light. In it druids dance while the narrator calls for people to gather underneath mistletoe and give praise to the sun. For many European nations like the Celts, and the Germanic peoples this festival in ancient times was one of the major ones of the year, full of rites and ceremonies of which some survived the ages like the bonfire/fireworks. During its spread over Europe, Christianity claimed this festival by 'implanting' Christmas as a festival of light on the 25th of December. The back of the sleeve of the "Solstice Bells"-EP (released in 1976) has a brief anecdote describing how the Church coopted the pagan winter solstice celebrating, Yule, and replaced it with Christmas.

* Jan Voorbij

I have a piece of news for you: I think that Ian made a blunder here! He talks about Druids, but evidence has been shown that the Celtic peoples, of whom the Druids were the priests, did not celebrate Solstices. The Celts had only four days of celebration in the year, namely Samain on the eve of November (our actual Halloween), which was their New Year's Day, Imbolc on the Eve of February (which has become French "chandeleur"), Beltane on the eve of May, and finally Lughnasad on the eve of August. Other Pagan peoples, mainly gothic tribes, celebrated the Winter's solstice as Yule, but the Celts never did. Perhaps Ian meant to use "druid" in the sense of "priest", but the Druids were only Celtic, and derive their name from the same root as the Latin verb for "see": etymologically, Dru-vides means "the far-seeing," that is those that could see that which normal human beings cannot (i.e. the gods or any supernatural manifestation.)

Where Ian is right though is in qualifying the Sun of "sister" and not "father" (more rarely "brother") as we are accustomed to. In Celtic languages the Sun was feminine and the Moon masculine, because Celtic people considered the power of life to be feminine in nature, and that the sun's heat and light was the expression of the Mother Goddess's power to give life. The distinction between Mother Goddess and "sister Sun" does not contradict this, because for Celtic peoples the Goddess embodied all types of women, hence she was mother, sister and lover at the s ame time.

(For more detailed information about Celtic civilisation, mythology and beliefs, I recommend the books written by Jean Markale. He is a French writer who has written many books on the Celts as well as on the Arthurian Legend, and you can find many of his works translated into English. Look for titles such as The Celts : Uncovering the Mythic and Historic Origins of Western Culture, Woman of the Celts, The Druids : Celtic Priests of Nature, or The Great Goddess : Reverence of the Divine Feminine from the Paleolithic to the Present.

* Fred Sowa

The Whistler

Like 'Velvet Green' this is a love song. The rural imagery continues. A man, presumably, offers to buy the object of his affection mares and apples. He talks of sunsets in 'mystical places', a line that bring the stone circles to mind. This image returns in 'Acres Wild' ("I'll make love to you (...) where the dance of ages is playing still") and in 'Dun Ringill' ("We'll wait in stone circles, till the force comes through (...) oh, and I'll take you quickly by Dun Ringill.").

"Songs from the wood : the music and lyrics of Ian Anderson", John Benninghouse; adaptation Jan Voorbij.

This song illustrates one of the key ideas of the album: that a happy life is a life without worries, and one only has to see the line "All kinds of sadness I've left behind me" to understand that. The narrator calls himself "the Whistler," i.e. the one that always whistles, as we usually do when we are happy and don't have anything to worry about. But "the Whistler" may also simply mean "the one who plays the whistle," and there is a good deal of tin-whistle in the music and the whole album.

This idea is corroborated by the line "I have a fife and a drum to play" in which the word "fife" is punctuated by a flying series of notes from Ian's flute, as the word "drum" is punctuated by the sound of a real drum. So the character is pictured as a flute-player, a new minstrel-like character, a concept that we know Ian is very fond of. And the main characteristic of this minstrel is that he is a wandering musician, as he explicitly tells us: "I am the first piper who calls the sweet tune / but I must be gone by the seventh day." So from the start he warns us that he can't stay with us, that he has to go elsewhere to spread his message of love to other people, but he does also say that we are welcome to follow him on his journey, in order to help him in his difficult task: "Climb in the saddle and whistle along", that is to say, "become Whistlers as well."

So I don't think that it is a love song at all, because there is no reference to a woman anywhere. I think rather that Ian wants to paint a new character of hope, the same herald or emissary as in the song "Songs from the Wood", who will speak on behalf of Nature. The line "But I'll be yours for ever and ever" certainly lends to confusion, but I think that what he means by that is that if we decide to follow him, he'll become our friend for life, just as in "Songs from the Wood" he says that if we join the chorus, i.e. if we sing and whistle with him, it'll make of us honest men, that is to say true in friendship.

"Deep red are the sun-sets in mystical places.

Black are the nights on summer-day sands.

We'll find the speck of truth in each riddle.

Hold the first grain of love in our hands."

Ha! Now we come to something which is very difficult to interpret! It sounds to me like pure poetry, that is to say words that may have a deeply hidden meaning which only the narrator knows, but it also resembles a kind of magical incantation. The last line is one of the most powerful Ian ever wrote: it is, as the grass growing through pavements in "Jack-in-the-Green", full of an overwhelming sensation of hope. The Whistler tells us that we will, with him, sow the seeds for a better world where love will be the lot of everyone, he invites us to follow him and to build this new world with him by joining hands in a sign of mutual friendship.

* Fred Sowa

Pibroch (Cap In Hand)

This is a song of unrequited love. A man is travelling through the woods to his love's home after hesitating for long to propose to her or express his feelings. He finds out, that he is too late for that, since there is another man with her. Pibrochs (in Gaelic: piobaireached) are a form of funeral music, dirge or lament, very hard to play and therefore also called 'big music' (ceol mor), quite different from the 'little music' (ceol beag): jigs, reels and strathspeys.

* Jan Voorbij

A pibroch is one of three traditional Scottish dances. They sound pretty well when being played by real highlanders; visit any Highland-Game anywhere in Scotland and you will hear a rich variety of Pibrochs being played.

* Clemens Bayer (SCC vol 9, nr. 14)

A pibroch is a formal Scottish dance, or series of variations on a theme played by bagpipes.

* Neil Thomasson (SCC vol.9 nr. 14)

Fire At Midnight

Once again a beautiful love song that describes the joy of coming home from a hard working day and spending time with one's wife. Ian said he wrote the song after a long day in the studio. The song breaths an atmosphere of relaxation, ease, harmony and - perhaps - gratitude.

* Jan Voorbij

The genius of Ian is to have placed this song at the end of the album, \line because it is the more hopeful of all, and because it acts as a closing \line scen e taking place at midnight, after "another working day" that might be \line the writing of the album, or the journey of the Whistler to teach people how \line to be happy. It inscribes itself in the continuity of the whole album and at \line the same time acts as a conclusion to it. I really think this is one of the \line most powerful songs Ian ever wrote, but it is a pity that it is so short!

* Fred Sowa

To summarize: the first album of the 'trilogy' is mostly celebratory. There are love songs, prurient songs and songs that celebrate nature and traditions c.q. folklore from ancient, pre-Christian religions, that were 'nature, earth based'. Modern society makes only the occasional intrusion into the green world painted by lyrics and music. 'Songs From The Wood' offers us some special qualities, and reveals an ingenuity that makes the album a masterpiece.

* Jan Voorbij

Beltane (2003 remaster only)

In this remarkable song, recorded in 1977 during the Heavy Horses sessions, Ian Anderson's capability of evoking sylvan and rural imagery comes to the fore in all self-penned originals. He applies images taken from the old Celtic Beltane festival. Hodgson points out, that against "the background of agrarian dependency and fear of the unknown there eventually developed two separate, yet connected cycles, each of four annual festivals. These were designed both to mirror the changing seasons and to secure the favour of the gods", referred to in this song: "... the phantoms of three thousand years...".

Beltane was possibly the biggest festival of all eight and took place on May Day itself, between midnight ("Have you ever stood in the April wood and called the new year in?") and sunrise ("and the red cloud hanging high").

The cult spread across Britain, ancient Gaul and as far as northern Italy and is by some believed to be named after the god Belenus (Baal?). "Winter was proclaimed dead for another year on this day and, aided by the moon, the sun was again declared victorious. Sacred fires were lit upon holy hills and flaming torches were carried around the fields to celebrate his triumph".

This festival and its rites were meant to ensure fertility for people, livestock and land, but also to bannish infertility, diseases and other evil. "People would dance sunwise around the fires and even jump through the flames so as to purify themselves for the coming year. They would then drive their livestock between the fires for similar reasons". Thus was the masculine, solar, sky-father annually joined with the feminine, lunar, eart-mother in accordance with each other and balance both in human life and nature as well was restored. Such was the belief.

Apart from dancing and singing, people supported the rejuvination by having sex in field and wood. ("Thrust your head between the breasts of the fertile innocent." (and) "while the kisses drop like a fall of shot from soft lips in the rain, come a Beltane.") Stories abound of young men and women running amok in the woods on the eve before the first of May. Church officials condemned such practices, swearing that a full two-thirds of the maidens returned home "defiled" (Lloyd, 106-107). For the pre-Christian peasant, however, these were not defiling acts: The first of May was seed time, and after planting it was believed that the seeds should be assisted in their fertilization. The sexual energy of the most virile members of the community was required to ensure the success of the crops (Lloyd, 106). Young couples copulated in the furrows of the fields to assist the crops along as well (99). As a result of these pagan practices, sexual imagery involving fields and farms is abundant (200)." I included some vivid descriptions of the Beltane festival further down this page.

Now back to the song itself. As for the darkly and glittering imagery this song has the same atmosphere as the "Heavy Horses" album and the only reason it was left out is in my opinion that the tenor of this song would have made it more appropriate to "Songs From The Wood", where Anderson implicitely pleads for a renewed care and respect for nature, tradition and sense of community as a remedy for the environmental pollution, pursuit of gain, and alienation that is so evident in today's society. I refer here specifically to the last stanza, were the link is made to "us here and now". Our surroundings (society?) for instance are described as "your parks and towns so knife-edged orderly". In spite of our striving to control nature, the green man goes his own way and reminds us of that ("... as the thin stick bites"), by rapping our knuckles with his cane. In this context the last "come a Beltane" sounds like a wish, a prayer maybe, for a new era in which people will be more caring for nature and themselves.... March the mad scientist springs to mind here....

Note the double twist in the imagery here: the "cane of sweet hazel" crashes down on the knuckles, but also on the window-sill! As if the boundary ('window') between fantasy/myth and the reality of life is broken by his warning blow.

* Jan Voorbij ; Source: "The Phantoms of 3000 Years, a look at some of the myths behind the music of Jethro Tull", Alan J. Hodgson, Birstal, UK (1993)

In the Central Highlands of Scotland, bonfires, known as the Beltane fires, were formerly kindled with great ceremony on the first of May, and the traces of human sacrifices at them were particularly clear and unequivocal. The custom of lighting the bonfires lasted in various places far into the eighteenth century, and the descriptions of the ceremony by writers of that period present such a curious and interesting picture of ancient heathendom surviving in our own country that I will reproduce them in the words of their authors.

The fullest of the descriptions is the one bequeathed to us by John Ramsay, laird of Ochtertyre, near Crieff, the patron of Robert Burns and the friend of Sir Walter Scott. He says:

"But the most considerable of the Druidical festivals is that of Beltane, or May-day, which was lately observed in some parts of the Highlands with extraordinary ceremonies . . . Like the other public worship of the Druids, the Beltane feast seems to have been performed on hills or eminenc e s. They thought it degrading to him whose temple is the universe, to suppose that he would dwell in any house made with hands. Their sacrifices were therefore offered in the open air, frequently upon the tops of hills, where they were presented with the grandest views of nature, and were nearest the seat of warmth and order. And, according to tradition, such was the manner of celebrating this festival in the Highlands within the last hundred years. But since the decline of superstition, it has been cel e brated by the people of each hamlet on some hill or rising ground around which their cattle were pasturing. Thither the young folks repaired in the morning, and cut a trench, on the summit of which a seat of turf was formed for the company. And in the middle a pile of wood or other fuel was placed, which of old they kindled i.e., forced-fire or need-fire [fire made by friction]. Although, for many years past, they have been contented with common fire, yet we shall now describe the process, because it will hereafter appear that recourse is still had to the "tein-eigin" upon extraordinary emergencies.

The night before, all the fires in the country were carefully extinguished, and next morning the materials for exciting this sacred fire were prepared. The most primitive method seems to be that which was used in the islands of Skye, Mull, and Tiree. A well-seasoned plank of oak was procured, in the midst of which a hole was bored. A wimble of the same timber was then applied, the end of which they fitted to the hole. But in some parts of the mainland the machinery was different. They used a frame of green wood, of a square form, in the centre of which was an axle-tree. In some places three times three persons, in others three times nine, were required for turning round by turns the axle-tree or wimble. If any of them had been guilty of murder, adultery, theft, or other atrocious crime, it was imagined either that the fire would not kindle, or that it would be devoid of its usual virtue. So soon as any sparks were emitted by means of the violent friction, they applied a species of agaric which grows on old birch-trees, and is very combustible. This fire had the appearance of being immediately derived from heaven, and manifold were the virtues ascribed to it. They esteemed it a preservative against witchcraft, and a sovereign remedy against malignant diseases, both in the human species and in cattle; and by it the strongest poisons were supposed to have their nature changed.

After kindling the bonfire with the " tein-eigin" the company prepared their victuals. And as soon as they had finished their meal, they amused themselves a while in singing and dancing round the fire. Towards the close of the entertainment, the person who officiated as master of the feast produced a large cake baked with eggs and scalloped round the edge, called "am bonnach beal-tine" i.e., the Beltane cake. It was divided into a number of pieces, and distributed in great form to the company. There was one particular piece which whoever got was called "cailleach beal-tine" i.e., the Beltane "carline", a term of great reproach. Upon his being known, part of the company laid hold of him and made a show of putting him into the fire; but the majority interposing, he was rescued. And in some places they laid him flat on the ground, making as if they would quarter him. Afterwards, he was pelted with egg-shells, and retained the odious appelation during the whole year. And while the feast was fresh in people's memory, they affected to speak of the "cailleach beal-tine" as dead."

In the parish of Callender, a beautiful district of western Perthshire, the Beltane custom was still in vogue towards the end of the eighteenth century. It has been described as follows by the parish minister of the time:

"Upon the first day of May, which is called "Beltan", or "Baltein" day, all the boys in a township or hamlet meet in the moors. They cut a table in the green sod, of a round figure, by casting a trench in the ground, of such circumference as to hold the whole company. They kindle a fire, and dress a repast of eggs and milk in the consistence of a custard. They knead a cake of oatmeal, which is toasted at the embers against a stone. After the custard is eaten up, they divide the cake in to so many portions, as similar as possible to one another in size and shape as there are persons in the company. They daub one of these portions all over with charcoal, until it be perfectly black. They put all the bits of the cake into a bonnet. Every one, blindfold, draws out a portion. He who holds the bonnet is entitled to the last bit. Whoever draws the black bit is the "devoted" person who is to be sacrificed to "Baal", whose favour they mean to implore, in rendering the year productive of the sustenance of man and beast. There is little doubt of these inhuman sacrifices having been once offered in this country, as well as in the east, although they now pass from the act of sacrificing, and only compel the "devoted" person to leap three times through the flames; with which the ceremonies of this festival are closed".

Thomas Pennant, who travelled in Perthshire in the year 1769, tells us that

"on the first of May, the herdsmen of every village hold their Bel-tien, a rural sacrifice. They cut a square trench on the ground, leaving the turf in the middle; on that they make a fire of wood, on which they dress a large caudle of eggs, butter, oatmeal and milk; and bring besides the ingredients of the caudle, plenty of beer and whisky; for each of the company must contribute something. The rites begin with spilling some of the caudle on the ground, by way of libation: on that everyone takes a cake of oatmeal, upon which are raised nine square knobs, each dedicated to some particular being, the supposed preserver of their flocks and herds, or to some particular animal, the real destroyer of them: each person then turns his face to the fire, breaks off a knob, and flinging it over his shoulders, says, "This I give to thee, preserve thou my horses; this to thee, preserve thou my sheep; and so on." After that, they use the same ceremony to the noxious animals: "This I give to thee, O fox! spare thou my lambs; this to thee, O hooded crow! this to thee, O eagle!" When the ceremony is over, they dine on the caudle; and after the feast is finished, what is left is hid by two persons deputed for that purpose; but on the next Sunday they reassemble, and finish the reliques of the first entertainment."

* Andy Jackson. The quotations are taken from: J.G. Frazer: "The Golden Bough", Abridged Version 1987 (cop. 1922), Macmillan (London), pp. 617-622

Jethro Tull - "Songs From the Wood" (1977) Ian Anderson had become a farmer, a fact that made a great impact on the music of Tull in the late 70's. "Songs From the Wood" is a wonderful album of Tull at their most folk and nature- inspired and with no doubt the best Tull-album from the second half of the 70's. The songwriting shows Anderson from his most inspired side, and the atmosphere and the arrangements are a dream for any nature-lover. The title-track is quite representative for the album. Great vocal-harmonies, complex parts with the typical rocking Tull-progressive but with a more folky feel than ever before. Other classics includes "Cup of Wonder", "Ring out Solstice Bells" and "Hunting Girl". And THEN you have the most progressive songs on the album: the completely genius "Velvet Green" and "Pibroch (Cap in Hand)". The whole album gives you a feeling of green valleys and forests, and I simply love it! Another essential Tull-album.