|

|

|

01 |

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band |

|

|

|

02:02 |

|

|

02 |

With A Little Help From My Friends |

|

|

|

02:44 |

|

|

03 |

Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds |

|

|

|

03:28 |

|

|

04 |

Getting Better |

|

|

|

02:47 |

|

|

05 |

Fixing A Hole |

|

|

|

02:36 |

|

|

06 |

She's Leaving Home |

|

|

|

03:35 |

|

|

07 |

Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite! |

|

|

|

02:37 |

|

|

08 |

Within You Without You |

|

|

|

05:05 |

|

|

09 |

When I'm Sixty-Four |

|

|

|

02:37 |

|

|

10 |

Lovely Rita |

|

|

|

02:42 |

|

|

11 |

Good Morning Good Morning |

|

|

|

02:41 |

|

|

12 |

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise) |

|

|

|

01:18 |

|

|

13 |

A Day In The Life |

|

|

|

05:33 |

|

|

|

| Country |

United Kingdom |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

1967 EMI Records Ltd. / Parlophone.

Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab [MFSL/OMR] #1-100

This is an excellent transfer to CD of the Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs original release of the album.

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Date of Release Jun 1, 1967

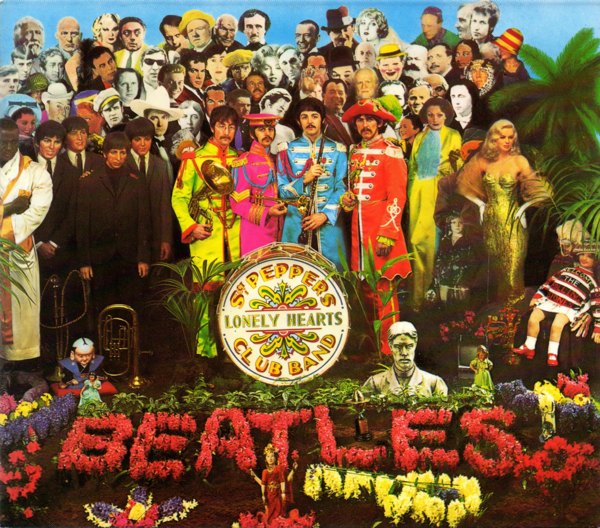

With Revolver, the Beatles made the Great Leap Forward, reaching a previously unheard-of level of sophistication and fearless experimentation. Sgt. Pepper, in many ways, refines that breakthrough, as the Beatles consciously synthesized such disparate influences as psychedelia, art-song, classical music, rock & roll, and music hall, often in the course of one song. Not once does the diversity seem forced - the genius of the record is how the vaudevillian "When I'm 64" seems like a logical extension of "Within You Without You" and how it provides a gateway to the chiming guitars of "Lovely Rita." There's no discounting the individual contributions of each member or their producer George Martin, but the preponderance of whimsy and self-conscious art gives the impression that Paul McCartney is the leader of the Lonely Hearts Club Band. He dominates the album in terms of compositions, setting the tone for the album with his unabashed melodicism and deviously clever arrangements. In comparison, Lennon's contributions seem fewer, and a couple of them are a little slight but his major statements are stunning. "With a Little Help from My Friends" is the ideal Ringo tune, a rolling, friendly pop song that hides genuine Lennon anguish, ala "Help!;" "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" remains one of the touchstones of British psychedelia; and he's the mastermind behind the bulk of "A Day in the Life," a haunting number that skillfuly blends Lennon's verse and chorus with McCartney's bridge. It's possible to argue that there are better Beatles albums, yet no album is as historically important as this. After Sgt. Pepper, there were no rules to follow - rock and pop bands could try anything, for better or worse. Ironically, few tried to achieve the sweeping, all-encompassing embrace of music as the Beatles did here. - Stephen Thomas Erlewine

1. Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Lennon/McCartney) - 2:02

2. With a Little Help from My Friends (Lennon/McCartney) - 2:44

3. Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds (Lennon/McCartney) - 3:28

4. Getting Better (Lennon/McCartney) - 2:47

5. Fixing a Hole (Lennon/McCartney) - 2:36

6. She's Leaving Home (Lennon/McCartney) - 3:35

7. Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite (Lennon/McCartney) - 2:37

8. Within You, Without You (Harrison) - 5:05

9. When I'm Sixty-Four (Lennon/McCartney) - 2:37

10. Lovely Rita (Lennon/McCartney) - 2:42

11. Good Morning, Good Morning (Lennon/McCartney) - 2:41

12. Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band... (Lennon/McCartney) - 1:18

13. A Day in the Life (Lennon/McCartney) - 5:33

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: The title track of the Beatles' most famous album, "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" - the song itself, not the album - was a bit of an anomaly for the group in that it wasn't intended so much as an outstanding track per se as it was one that could serve for the theme tune of the entire LP. Had it not been in the context of the Sgt. Pepper album, it would have been no more than an average Beatles song. As the curtain-raiser to their most grandiose full-length statement, however, it was key to setting the mood of a psychedelic record that was - unlike previous Beatles albums, and most previous rock albums by anyone - something of a psychedelic revue and variety show. The illusion of the album being a theatrical presentation of sorts was established by the opening bars of crowd noise and a pit orchestra tuning up. When the Beatles do start playing, it's in a rather heavy, funky psychedelic rock style, paced by stinging hard rock guitar and Paul McCartney's typically forceful, exuberant upper-register soul-rock vocals. As a taster of the kaleidoscopic shifts to come over the course of the next dozen songs, however, it suddenly shifts into an instrumental fanfare that could have been played by a brass band of the 18th or 19th century in a British public park. The McCartney-sung first verse had already made it clear that this was supposed to be a show of some sort, as, like a singing emcee, he presents and introduces the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Wittily, in the section following the instrumental brass band passage, the Beatles become the fictional Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. They announce themselves in a grandstanding fashion and exhort the equally fictional audience (which can be heard oohing, aahing, and applauding at the appropriate audiences) to sit back and enjoy the show. One can almost see the Beatles, decked out in the gaudy band costumes they wear on the Sgt. Pepper sleeve, doing showbiz dance steps in time to the music. There is understated irony, perhaps, in their deadpan delivery of bland showbiz cliches about it being wonderful to be here, hoping that the audience will enjoy the show, and wishing they could take the audience home with them: the Beatles had made a career of undermining show business conventions, and the subsequent program on the Sgt. Pepper album will be anything but conventional family matinee entertainment. Then it's back to the verse, McCartney again taking over in his best belting style and maintaining the imaginary music hall setting by introducing one Billy Shears. Applause and then ecstatic shrieks (a sarcastic reference to Beatlemania perhaps?) follow as the track segues into "With a Little Help From My Friends," the Billy Shears part apparently donned by vocalist Ringo Starr. The "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" song itself would be reprised briefly near the end of the album in a far more rock-oriented version that concentrated solely on the portion in which the Beatles introduced themselves (rephrased so that they were saying goodbye to the audience). Because of its integral position within the context of a semi-conceptual album, "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" wasn't the easiest song to cover, but one superstar would do so immediately. Jimi Hendrix opened his June 4, 1967, show at London's Saville Theatre with his own heavy rock version of the number, although the album had only been out for three days. Paul McCartney was in the audience, and seems to regard it as perhaps the most flattering Beatles cover of all, calling it "one of the great honors of my career" in his autobiography. Hendrix did not record the tune for his studio albums, but would return to it in concert throughout his career; a live version he did at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival appeared on the posthumous Hendrix in the West album. - Richie Unterberger

With a Little Help from My Friends

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: Ringo Starr did not sing often on Beatles records, and with the exception of the hit "Yellow Submarine," had not been granted a lead vocal on any of the group's more important tracks before 1967. For "With a Little Help From My Friends," however, he would take center stage on one of Sgt. Pepper's key songs - the first one, in fact, aside from the opening title cut, which was more of a curtain-raising theme song than a proper Beatles tune. "With a Little Help From My Friends" is one of the jauntiest, cheeriest songs in the entire Beatles catalog. It's certainly one of their most optimistic, feel-good statements, gently asserting that everything will work out with friends around to help one out. On that level it can certainly be legitimately enjoyed and appreciated, but for those who care to look, there are some deeper emotional resonances and shades as well. It is interesting that such a peppy song, for one thing, was assigned to Ringo Starr, often noted for the sorrowful quality of his vocals, although it's likely that Lennon and McCartney had nothing more in mind than making sure Starr had a song to sing on the album. Starr's everyman persona, in any case, was suitable for the humility, even vague self-doubt, of the lyrics, which fretted over whether the audience would walk out on him if he sang out of key, and plaintively announced that he needed somebody to love. The song's effectiveness is increased manifold by the use of question-and-answer structure between Starr and harmonizing vocalists starting with the second verse. There was one line in particular that was naughty in a way that should have been obvious even by 1967 standards: the one asking what the narrator sees when he turns out the light, to which Starr replies that he can't say, but he knows it's his. The final chorus, in a manner consistent with the ostensible musical revue "With a Little Help From My Friends" is kicking off, changes the melody a little so that it can end with a grandstanding ensemble vocalization of the word "friends," Starr's straining lead vocal set off by counterpoint descending harmonies. One can picture the Beatles, if they were indeed performing this song at the fictional concert that is Sgt. Pepper, exhorting the audience to join in for that finale. Journeyman British soul singer Joe Cocker became an instant star when he covered the song in late 1968, taking it to number one in the U.K. with a radical, and quite good, pure soul reinterpretation. The drastically slowed tempo of the verses increased the emotional intensity of the song, which sounded in Cocker's hands more like a serious, yearning plea than a chipper singalong. Cocker also made the choruses into wrenching, heavy hard rock with stinging, anguished guitar licks. Although Cocker's version was not a hit in the U.S., his gritty, gravelly rendition helped make him a star stateside when he performed it at Woodstock, as seen in a famous sequence from the film of the festival (and heard on the Woodstock soundtrack album). - Richie Unterberger

Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" was one of the best songs on the Beatles' famous Sgt. Pepper album, and one of the classic songs of psychedelia as a whole. There are few other songs that so successfully evoke a dream world, in both the sonic textures and words. The hallucinogenic quality of the production was emphasized by the initials of the main words in the title, which, as was no secret even when it was first released, spell LSD. That was a controversial happenstance that the Beatles, and principal author John Lennon, would spend decades answering. Lennon, for his own part, always insisted that the title derived from his three-year-old son Julian Lennon's description of a painting he had done in nursery school, Lucy being a girl in his class. (The original painting, and a picture of the real-life Lucy, can be seen on pages 122-123 of Steve Turner's book -A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every eatles' Song.) That was certainly a remarkable coincidence, but regardless of whether the lettering was intentional or not, the psychedelic quality of the song's reverie would have been noted whether the initials spelled LSD or something else. The gorgeous melody of the opening lines is amplified by Lennon's unearthly, almost whispery vocals and the delicate unaccompanied keyboard, a Lowry organ made to sound like a celeste. The lyrics, whether ingested with the aid of substances or not, are very much like those seen in a dream, with the images of tangerine trees, marmalade skies, kaleidoscope eyes, cellophane flowers, and newspaper taxis. The song also unfolds with the lack of linear logic that characterizes dreams, starting on a boat, following an enchanting girl to a fountain, your head suddenly in the clouds, the girl mysteriously reappearing and disappearing. The pace of the song picks up after the first few lines, made more emphatic by the introduction of a pumping bass, then bursting into a chorus with much harder rock instrumentation and exultant vocal harmonies. The end of that chorus, with a wordless harmony suddenly fading as Lennon goes back into the quiet verse, creates the appropriate sensation in the listener of falling back into a dream. Occasional subtle tamboura drone (played by George Harrison) embellishes the exotic ambience. Although John Lennon usually eschewed descriptive story songs in favor of compositions that expressed an intensely personal point of view, in 1967 his songs tended toward observational imagery, as if trying to record the pictures in his head during his drug experiments. "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" is certainly the most successful and enchanting of his efforts in this direction, completed with some help from Paul McCartney (who contributed the cellophane flowers and newspaper taxis references, for example). In the mid-'70s, Elton John took a far less exotic and more ordinary version of "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" to number one, with Lennon singing backing vocals and playing guitar. The principal difference in arrangement - which sounds like an almost gratuitous, smug touch - was doing part of the song in a reggae tempo. Star Trek star William Shatner recorded a ludicrous spoken word-recital version that has drawn some guffaws for its camp value. - Richie Unterberger

Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: One of the strengths of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album was its eclecticism, moving from hard rock and chamber music to psychedelia, vaudeville, and good-time music. In this gallery of moods and stages, "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" is the circus, with its ringside description and helter-skelter whirl of fun house sounds providing a suitable closer to side one (on the original LP; of course, on the CD reissue, it is merely the seventh song). Judged solely as a composition, "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" - written more by John Lennon than Paul McCartney, although they did collaborate - isn't much of a song. Lennon quickly admitted that most of the lyrics were lifted, almost word-for-word, from an 1843 poster for an English circus. What made "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" work, within the context of Sgt. Pepper's certainly, was the ingenuity of the arrangement, devised with much input from producer George Martin. A hurdy-gurdy circus melody established the appropriate atmosphere, especially via the harmonium part, played by Martin himself, which seemed lifted right off a merry-go-round soundtrack. Ringo Starr deserves credit for the dramatic drum roll that introduces the first verse, in the manner of a circus orchestra introducing a lion tamer or tightrope walker, as well as keeping the rhythm going during the verse with tense jazzy cymbals suitable for pre-World War II theatrical productions. The psychedelic element of "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" came into play in the instrumental break, in which the merry-go-round circus ambience sped up into a swirl of sound that seemed on the verge of getting out of control before being brought back to its senses by a pounding honky tonk piano. After one more verse, it was back into another wild instrumental circus break, this time weirder and more uncontrollable than the middle break, with a somewhat sinister undertone before coming to a sudden dead stop. As on cuts like "Tomorrow Never Knows," the Beatles and Martin pulled out all the stops to make a layer of sound that was only possible to create in the recording studio. Tapes of calliopes and military marches were chopped into pieces and stitched back together at random, resulting in a sound both redolent of the circuses of bygone days, and as avant-garde as anything in rock music. - Richie Unterberger

Lovely Rita

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "Lovely Rita" was one of the more lighthearted songs on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, and consequently one of the more critically overlooked. It was among the more tuneful tracks on the album, though, and while it wasn't singles material or something destined to become a standard, it was a good example of principal composer Paul McCartney's knack for ingratiating character sketches. (As one of the less exotic songs on the album, it also stood by itself, out of context from its surrounding compositions, more sturdily than some of the other selections did.) Like some of McCartney's late-'60s compositions (such as "Maxwell's Silver Hammer"), there was a possible influence from Ray Davies of the Kinks in its jauntily British, wryly humorous tale of an everyday scenario in which there might be more than meets the eye. To stretch that Davies similarity a bit further, there is a hint of odd gender ambiguity and reversal in the description of the meter maid who is "Lovely Rita," with a uniform that makes her look a little like a military man. It's also odd that Rita pays the bill when the narrator takes her out to dinner (this is just pre-women's liberation, remember) and that he implies he almost manages to seduce her while sitting on a sofa with a sister or two. Another of the very subtle naughty sexual references the Beatles put in their songs from time to time? (And if you want to really stretch the Davies comparison, note that Ray Davies had written a Kinks B-side in 1966 called "Sitting on My Sofa.") McCartney's upbeat vocal is supported by some very nice Beatles harmonies on the chorus and a bit of deftly woven counterpoint harmony in the verse. Producer George Martin, always on hand to provide the appropriate extra bit, does a suitable honky tonk piano in the instrumental break (as he had done in a previous upbeat Beatles cut, "Good Day Sunshine"). The odd instrumental tag, in contrast to the rest of the song, goes into a bit of melancholy melody that is daft in a slightly menacing fashion, whereas the rest of the song is daft in a good-natured manner. Against the sad piano chording, the Beatles make strange animal-like noises, as well as blowing on combs covered with toilet papers to produce kazoo-like tones, ending with stuttering piano notes before coming to a conclusion with a grand flourish down the keys. Fats Domino did a none-too-thrilling soul cover of "Lovely Rita" on his 1968 comeback album Fats Is Back, a record more noted for its cover of "Lady Madonna." - Richie Unterberger

Day in the Life

Composed By John Lennon/Paul McCartney

AMG REVIEW: "A Day in the Life" was one of the most complex and ambitious Lennon- McCartney songs performed by the Beatles, providing an incendiary climax for their Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album. It was also the most outstanding instance in which two discrete song fragments - one primarily by John Lennon, the other by Paul McCartney - were combined into one to build a whole greater than the sum of the parts. "A Day in the Life" is an unexpectedly mordant coda to an album noted for epitomizing the Summer of Love. The main verses of the song are Lennon's work, a rather gloomy first-person narrative of going through the motions and observing, in a detached manner, the cruelties and absurdities of the everyday world. As the Beatles often did, the specific lyrical references are drawn from bits of news and personal experience. The death in a car crash was that of socialite and Beatles acquaintance Tara Browne (not of Paul McCartney, as would often be speculated a few years later during the "Paul Is Dead" rumors); the film about the English army winning the war was How I Won the War, in which John Lennon had acted. The dramatic tension is aided by Ringo Starr's crafty, thundering drum accents, but had it remained unembellished, Lennon's piece of the song would have been little more than a pensive, almost folky rumination. After the initial verses and Lennon's celebrated invitation to turn the listener on, however, the song mutates into something quite different, a dissonant orchestral crescendo that is simultaneously nightmarish and exhilarating. As is heard in several of Lennon's songs in 1966 and 1967, he seems largely uninterested in the outside world, and more intrigued by withdrawing into himself and the mind, whether with the aid of psychedelic chemicals or otherwise. The orchestral section suddenly ends just as it seems it can't wind itself into any higher a key, immediately followed by a basic, jaunty McCartney tune about waking up and going to work. By itself, this McCartney tune certainly wouldn't have been much. What made it effective was its juxtaposition next to Lennon's dreamier sections. The implication seemed to be that Lennon's was the dream world, and McCartney's a literal rude awakening to reality, ending when the narrator of McCartney's bit slides back into a dream. Lennon then takes over again, with haunting wordless vocals of Olympian import, ending with a brief brass fanfare before the last verse. In contrast to the opening verses, though, this final run-through is perky, with a far livelier, almost rushed rhythm, as if it was a compromise between the earlier moods of the song. Again this turns into a frightening orchestral crescendo, its dissonance unified by nothing more than a rising key, ending with what might be the most famous finale in all of rock: a momentous, echoing piano chord, sustained for almost a full minute (actually played simultaneously on three separate pianos by three Beatles and roadie Mal Evans). - Richie Unterberger

THE BEATLES

SGT. PEPPER'S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND

Where did progressive or symphonic rock start ? To this question, many answers are possible. My answer would be: 'with Sgt.Pepper'.

This album has become known as the very first concept album. Besides that, The Beatles surprised everyone with the complexity of both compositions and sound.

The recording-sessions for this album started early November 1966, just after The Beatles announced that they wouldn't play live again. During the recording-sessions for Revolver the band had discovered that new techniques could stretch boundaries for them and that it wouldn't be possible to play their new compositions live.

The first songs recorded for the album, Strawberry Fields and Penny Lane, didn't make it to the album, since the record-company wanted to release a single, because the fans hadn't heard from the band for almost a year (Hey, Peter Gabriel, can you imagine?). As a result these 2 songs were released as single before the release of Sgt.Pepper. Producer George Martin later called this 'the biggest mistake of his life'. In the CD-era the songs would have been on the album as well, but this wasn't the case then.

Nevertheless these two songs were essential to the rest of the album because they set the standard for the other tracks. Both songs were youth-memories and both writers, McCartney (Penny Lane) and Lennon (Strawberry Fields), really made a big effort to make their won track better than the other. Lennon needed no less than 26 takes and 10 days for only one song. Anyone who knows 'take one' knows how it developed in that time.

To the album now. In the title track The Sgt.Peppers Lonely Hearts Club band is presented to the audience. By doing this, The Beatles 'escaped' from their image. Weird costumes and moustaches helped creating a different atmosphere.

This opening track is still one of my favourite Beatles-songs. The orchestra and the rhythm of the guitars form a unique powerful combination. A different (faster) version, recorded two months later, is the reprise on side two of the original album.

With a Little Help From My Friends, follows. Ringo Starr (in his role of Billy Shears) sings this track and starts with asking us to forgive him for singing out of tune; a smart move! This song was later made number one in different version by Joe Cocker.

Next is Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. This track was banned from the BBC, because it featured the capitals LSD. John Lennon explained that he was unconscious of this and that it was named after a drawing by his son Julian (for who McCartney later wrote 'Hey Jude'). Fact is that The Beatles experimented a lot with different drugs, which added to the psychedelic atmosphere of the album.

Getting Better is a typical result of the co-operation between the optimistic McCartney and the cynical Lennon. This song was recently used for a Philips commercial: "You've got to admit, it's getting better". Funny enough Philips left out the next line, John Lennon's cynical "It can't get no worse"...

Fixing A Hole was moved several times in the track-list and finally put on this prominent sport on the record. George Martin liked it because of the wonderful bass-line and his is completely right about that.

She's Leaving Home is another result of real co-operation between Lennon and McCartney. This is one of the very few tracks that wasn't orchestrated by George Martin. McCartney simple thought it took too long and he asked someone else to do it. Lennon and McCartney both sing a part, only accompanied by the orchestra (isn't that symphonic?).

After John's "Bye, Bye" side one originally ended, but Being For The Benefit of Mr.Kite, was moved to this spot. Remarkably enough, the booklet of the CD suggest the listener to correct this with the help of the Cd-player. The track originally was the third song on the album and I think it suited better on that place.

Like Strawberry Fields, The Benefit... shows the creativeness of John Lennon. Inspired by a circus-poster he wrote this track about clowns, horses, wild animals etc. He originally wanted a real 'steam-organ' to accompany the song, but this was impossible. To create the same feeling, George Martin played the melody on a 'normal' organ and added a lot of short bits and pieces from fairy-organs as background-noise. The result is great.

The second side of the album starts with one of the strangest songs The Beatles have recorded. Some fans hate it, others think it's brilliant. It was something completely unusual in any case. George Harrison wrote this track, called Within You Without You, inspired by India, a country that had caught, because of it's spirituality, the attention of The Beatles. The tabla and sitar that are used to play this song are authentic Indian instruments. Personally, I like this experiment, but it's a bit too long for me. It doesn't make a great start for the second side.

When I'm Sixty-Four and Lovely Rita are both added at a later moment to the tracklist, in stead of the aforementioned (single-)tracks. Both songs are written by McCartney. When he wrote '64' he was about 16, so the song was recorded a bit faster, in order to make him sound a bit younger.

Like Lovely Rita, Good Morning, Good Morning (a Lennon compostion) was especially made interesting with the help of many sound effects. The sound of the rooster at the beginning and the hurdle of animals running from left to right on your stereo-version (there originally also was a slightly different mono-version) form a nice bridge to the faster reprise of Sgt.Pepper, immediately followed by A Day In The Life. A Day In The Life is the result of a true co-operation between Lennon, McCartney and Martin (see picture left). The almost cynical tone of Lennon's remarks to the morning-paper, contrast with the optimistic part in which McCartney gets out of bed. Martin adds the climax, a bombastic, sweeping symphony orchestra that accompanies Lennon's "I love to turn you on" in a great way. In my view, A Day In The Life, with all it's twists and turns including a bombastic symphony orchestra, set a standard for every symphonic rock song that has been made ever since.

Writing and production of an album was never the same after Sgt. Pepper.

Jan-Jaap de Haan

The Beatles - Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Member: Thekouderwunz - 02/22/03

In 1967, a quartet of ambitious pop rockers, were innovatively changing the facet of music during the Sixties, providing the world with a plethora of timeless singles that still to this day, many have become standards, covered by many artists in the pop, jazz, classical genres, but it was with the innovative Revolver album that The Beatles began to focus on their maturation since the release of their Help album.

Many things had changed with the four members of The Beatles since the Help album, on their first trip to the US, a meeting with Sixties icon, Bob Dylan, introduced the band to mind altering substances which would fuel the band's creativity, but the down side was that it also fueled their paranoia, and in 1966 the band put an end to their live show, but such a bold move proved to be a blessing in disguise, the band reverted to the studio work, but to keep their fans happy whom were now no longer to see The Beatles live, pioneered the use of "promo" films, which we now call music videos.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney had a falling out over the musical directions that both individuals were going and no longer wrote songs together, but due to contractual purposes, the songwriting collaboration still existed, George Harrison was becoming more confident not only in his innovative "slide" guitar work, but he was becoming a prolific writer within the band as well.

Sometime in 1967, The Beatles, with an unlimited budget, went into the studio, and decided that they were going to make an album of a fictional being by the name of Sgt. Pepper.

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club Band is a wonderful, and overtly ambitious album that musically was a mix of power rock, baroque classical motifs, with vaudeville glee, ethnic world fusion, Dylan/Byrds folk all harmlessly blended together with the druggy connotations of psychedelia.

Most of the songs on Sgt. Pepper segue into each other in suite like form, which was unlike anything that any commercially POPULAR bands, were doing at the time. Many of the songs on Sgt. Pepper also went onto become FM radio staples, and standards that even nearly three and a half decades after its release, is still influencing many musicians whom grace their ears with this album.

From the shmaltzy "Sgt Pepper", drugginess of "A Little Help From My Friends" and "Lucy In The Sky" and psychobabble of "Being For The Benefit For Mr. Kite", lovely ballad "She's Leaving Home" in which the band is only captured on vocals, while being accompanied by a live orchestra, Harrison's Indian-themed "Within You", schizophrenic "Good Morning" and the finales to "Sgt. Pepper", a harsher reprise of the title track, and in what some deem to be the quintessential psychedelic track, "A Day In A Life" are amongst the highlights upon an album meant for one whole concentrated listening.

Many argue Jimi Hendrix's importance, on whether or not he is the greatest guitarist of his era, such a thing is hard to say as he played with some of the most greatest guitarists to ever strap on the guitar, but no one should ever question his innovative style, and his unprofound influence since then. So what does that have to do with The Beatles and Sgt. Pepper? Many historians, cite The Moody Blues' Days of Future Passed as the first art-rock album, some also say that it is Pink Floyd's Piper's At The Gates Of Dawn, while some consider the Cantenbury band Wilde Flowers to be the first true art-rock band, Or was it King Crimson and their progressive opus, In The Court Of The Crimson King?

Sgt. Pepper as we listen to it in comparison to what was to come in the Seventies, when groups like Yes, Emerson, Lake and Palmer and Genesis (to name a few) would stretch the boundaries and set the precedence to what we now know as "progressive rock", but Sgt. Pepper had a major influence on many of the Beatles peers, as some tried in vain (very few succeeded, like Family's In A Doll's House, Procol Harum's Shine On Brightly, The Soft Machine's Volume 1) in trying to capitalize on this album's innovations. Those that did succeed, influenced the most important bands of the progressive rock genre, which in turn influenced the neo-proggers and so forth.

Sgt. Pepper might not measure up to most of the progressive rock albums that came in its wake, but it does serves as its "blueprint".

A great step not only for "art-rock", but for music in general.

Charles

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Member: Cittorah 10/1/03

A few notes on a big hoax

1) The term "psychedelic," which is how much popular music of the sixties has come to be labeled, Sgt. Pepper included, is something rock critics also seem to think came new into the world sometime in 1966. In fact, "psychedelic" was really just the then-contemporary label for "surrealist", an ideology which had been around for decades, and which had roots deep into the nineteenth century, albeit surrealism was associated almost exclusively with painting, to a lesser degree, literature, and mainly with the expanding of the senses by means of the use of LSD-25.

2) The longest explanations you will mostly find regarding this album's influence are one sentence long. This includes all major music encyclopedias, and all major online sites such as all-music.

There's a reason for this: it wasn't an influential or important release at all. This album sounded dated by 1969. It sounds dated because it had nothing to do with the direction that rock music took. Allmusic [web site] offers one sentence to explain that "After Sgt. Pepper, there were no rules to follow" - yeah, perhaps, if those rules are related to printed lyrics and expensive cover art, the only true "innovations" of this album. The supposed "authorities" on music make such ridiculous statements. It's no wonder there is so much nonsense said about this album.

Non-critics make even stranger statements which are as equally false: it was so important because it was the first concept album and turned music (not just 'rock') into art. Even if it were a concept album, which it isn't, it still wouldn't have been the first. Other musicians beat them to it. Not that this explains why a concept album would be so important in the first place. Some reviewer claimed that "even if it wasn't the first concept album, it was the first to be CALLED as such", and is thus the most important album ever, or whatever else they'll claim. I think that speaks for itself.

Truth be told, other albums from earlier in 1967 and 1966 are far more adventurous, experimental, and ground-breaking, and they all sound far more contemporary than Sgt Pepper. Some examples-: Blonde on Blonde, Freak Out, Velvet Underground & Nico, Parable of Arable Land, Pet Sounds, Are You Experienced, The Doors, etc. None of these albums followed any rules, and they are all worthy of being called "serious", or "art". How is Peppe any closer to being 'art' than Blonde on Blonde?

And all these albums were NOT influenced by Sgt. Pepper. They pre-date it, afterall. Mind you, this wont stop some Beatle maniacs from making the claim that they were influenced by Pepper.

This album is more a cultural milestone than a musical one. An album is no more or less important because of how the public immediately receive it. Charts and sales-figures were just as meaningless back then as they are now.

If you do what no one else dares to do, and compare Sgt. Pepper with the truly influential albums of the 60s (such as White Light/White Heat), you'll make the astounding discovery that Sgt. Pepper sounds incredibly outdated. All this before the '60s were even over.

Sgt. Pepper is said to be the most influential album, not because of anything that happened to music after 1967, or in the 70s, or 80s, or 90s, but because we have been told to believe that it was. Nothing more. (This accounts for the one-sentence explanations of its influence.)

So what music did it directly influence? Satanic Majesties and a few other half-baked "concept" albums? Anything else? Not that I've found. So what is the big deal?

No commentary of Sgt. Pepper ever mentions the album in regards to what was going on with music in the late 60s. It never happens. The Beatles were simply a retro pop band. It was the other bands who paved the way and gave rise to the many genres of music that came out of the mid to late 60s.

Sgt. Peppers didn't even have influence over the music of 1968 or 1969: it had nothing to do with hard-rock, or heavy metal, or the back-to-basics production of 1968, or improvised music, or country rock, or experimental rock, or jazz fusion, or live music, or prog rock, or arena rock and so on. If you are knowledgeable about the late 60s and early 70s you will realise that rock music actually went in the exact opposite direction to everything the Beatles and especially Sgt. Pepper stood for. In successive decades the album was simply irrelevant.

This album wasn't a catalyst for change, it was simply released at the right time to receive the credit for everything that happened during the decade. This includes genres of music that had nothing to do with the Beatles music. But most people are only aware of the Beatles, so they assume they began it all.

POP MUSIC is the way it is today thanks to the Beatles -: massive hype, shallow lyrics, teen-idols, cute faces, boy-bands (whose hairstyles are as famous as the songs. whose members are known as "The cute one", "the shy one" etc), fads, merchandise, TV appearances, catchy hit singles, and so on and so forth. Thanks boys.

ROCK MUSIC is the way it is today thanks to The Rolling Stones, The Stooges, the Velvet Underground, The MC5, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Pink Floyd, The Doors, Led Zeppelin, Captain Beefheart, Cream, Frank Zappa, The Who, and others. And that's not even mentioning non-60s artists. All of these bands and artists released rock albums which have proven to be far more influential and important than Sgt Pepper's. None have dated as badly as Pepper, which obviously shows us which bands were ahead of their time, and which band was retro. Almost every important rock album of the last 30 years can be traced to one of these bands.

Note also: most comments about Sgt. Pepper have little to do with the actual (forgettable) songs on it. It is the hype and aura of this album that sustains the talk, not the songs. "Day in the life" is the only track on Peppers that deserves repeated listens anyway. It should also be pointed out that if rock music wasn't a "serious" art in 1967, it follows that there were no serious rock critics in 1967.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

c2001 - 2003 Progressive Ears

All Rights Reserved