|

|

|

01 |

Lucky Day Overture |

|

|

|

02:27 |

|

|

02 |

The Black Rider |

|

|

|

03:21 |

|

|

03 |

November |

|

|

|

02:53 |

|

|

04 |

Just The Right Bullets |

|

|

|

03:35 |

|

|

05 |

Black Box Theme |

|

|

|

02:42 |

|

|

06 |

T'ain't No Sin |

|

|

|

02:25 |

|

|

07 |

Flash Pan Hunter/Intro |

|

|

|

01:09 |

|

|

08 |

That's The Way |

|

|

|

01:07 |

|

|

09 |

The Briar And The Rose |

|

|

|

03:50 |

|

|

10 |

Russian Dance |

|

|

|

03:12 |

|

|

11 |

Gospel Train / Orchestra |

|

|

|

02:33 |

|

|

12 |

I'll Shoot The Moon |

|

|

|

03:51 |

|

|

13 |

Flash Pan Hunter |

|

|

|

03:10 |

|

|

14 |

Crossroads |

|

|

|

02:43 |

|

|

15 |

Gospel Train |

|

|

|

04:43 |

|

|

16 |

Interlude |

|

|

|

00:18 |

|

|

17 |

Oily Night |

|

|

|

04:23 |

|

|

18 |

Lucky Day |

|

|

|

03:43 |

|

|

19 |

The Last Rose Of Summer |

|

|

|

02:07 |

|

|

20 |

Carnival |

|

|

|

01:16 |

|

|

|

| Country |

USA |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

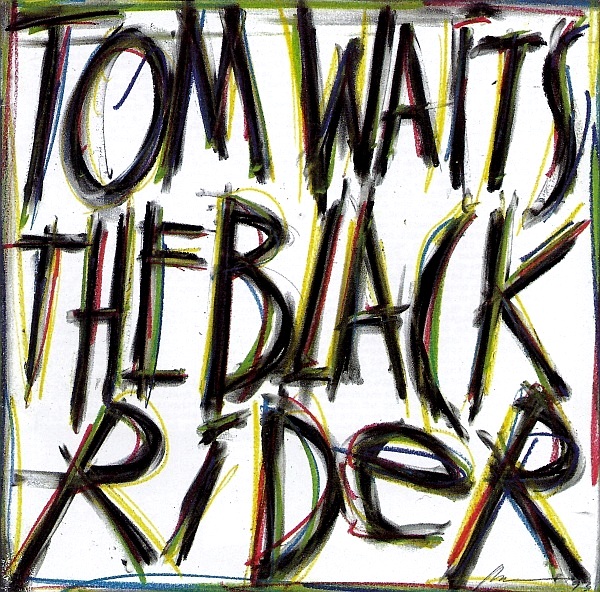

The Black Rider, 1993

(P) & c 1993 Island Records, Inc. The copyright in this sound recording and artwork is owned by Island Records Inc. and is exclusively licensend to Island Records Ltd in the UK.

c 1990, 1993 Jalma Music, Inc. except: "That's The Way", " Flash Pan Hunter" and "Crossroads" c 1990, 1993 published by Jalma Music, Inc./ Nova Lack Music (ASCAP).

"Ain't No Sin" c 1992 Edgar Leslie, published by Laurence Wright Music Co. Ltd/ EMI Music Publising Ltd.

Tom Waits: producer, arranger, vocals, Coliope ("Lucky Day - Overture"), organ ("The Black Rider", "Lucky Day", "The Last Rose Of Summer"), piano ("November", "Just The Right Bullets"), banjo ("November"), Chamberlain ("Black Box Theme", "Crossroads", "The Last Rose Of Summer", "Carnival"), Marimba ("'T 'Ain't No Sin"), Emax strings ("'T 'Ain't No Sin", "Russian Dance", "Carnival"), boots ("Russian Dance"), guitar ("Crossroads"), train whistle ("Gospel Train"), conga ("Gospel Train"), log drum ("Gospel Train")

Ralph Carney: sax ("Lucky Day - Overture", "I'll Shoot The Moon", "Oily Night"), bass, clarinet ("Just The Right Bullets", "Gospel Train - Orch.", "Flash Pan Hunter", "Gospel Train", "Oily Night"), baritone horn ("Lucky Day")

Bill Douglas: bass ("Lucky Day - Overture", "Just The Right Bullets", "Black Box Theme", "Russian Dance", "Gospel Train - Orch.", "I'll Shoot The Moon", "Flash Pan Hunter", "Gospel Train", "Oily Night", "Lucky Day")

Kenny Wollesen: percussion ("Lucky Day - Overture", "Just The Right Bullets", "Black Box Theme", "Gospel Train - Orch.", "I'll Shoot The Moon", "Flash Pan Hunter", "Oily Night", "Lucky Day"), marimba ("I'll Shoot The Moon")

Matt(hew) Brubeck: cello ("Lucky Day - Overture", "Just The Right Bullets", "Black Box Theme", "Russian Dance", "Gospel Train - Orch.", "I'll Shoot The Moon", "Flash Pan Hunter", "Oily Night", "Lucky Day")

Joe Gore: banjo ("Lucky Day - Overture", "Just The Right Bullets", "Black Box Theme", "Flash Pan Hunter", "Oily Night"), guitar ("Gospel Train - Orch.", "I'll Shoot The Moon", "Oily Night", "Lucky Day")

Nick Phelps: French horn ("Lucky Day - Overture", "Black Box Theme", "Gospel Train - Orch.", "Oily Night")

Kevin Porter: trombone ("Lucky Day - Overture", "Gospel Train - Orch.", "I'll Shoot The Moon", "Oily Night")

Greg Cohen: co-arranger ("The Black Rider", "Black Box Theme", "'T 'Ain't No Sin", "Just The Right Bullets", "Flash Pan Hunter"), writer and arranger ("Interlude"), arranger (Flash Pan Hunter - Intro"), bass ("The Black Rider", "November", "Crossroads", "Gospel Train", "The Last Rose Of Summer", "Carnival"), percussion ("The Black Rider", "Gospel Train"), banjo ("The Black Rider"), viola ("The Black Rider"), accordion ("November"), bass clarinet ("'T 'Ain't No Sin"), Emax strings ("'T 'Ain't No Sin")

Larry Rhodes: bassoon ("Just The Right Bullets", "Black Box Theme", "Gospel Train - Orch.", "Flash Pan Hunter"), contra bassoon ("Oily Night")

Francis Thumm: organ ("Just The Right Bullets", "I'll Shoot The Moon", "Flash Pan Hunter"), boots ("Russian Dance")

Don Neely: musical saw ("Black Box Theme", "Flash Pan Hunter")

William Burroughs: vocals ("'T 'Ain't No Sin"), lyrics ("That's The Way", "Flash Pan Hunter", "Crossroads")

Henning Stoll: contra bassoon ("Flash Pan Hunter - intro", "Interlude"), viola ("That's The Way", "The Briar And The Rose")

Stephan Schafer: bass ("Flash Pan Hunter - intro", "That's The Way", "The Briar And The Rose")

Volker Hemken: clarinet ("Flash Pan Hunter - intro", "That's The Way", "The Briar And The Rose", "Interlude")

Hans-Jorn Braudenberg: organ ("That's The Way", "The Briar And The Rose")

Linda Deluca: viola ("Russian Dance", "Gospel Train - Orch.", "Oily Night")

Kathleen Brennan-Waits: co-producer, boots ("Russian Dance")

Clive Butters: boots ("Russian Dance")

Christoph Moinian: french horn ("Interlude")

Tchad Blake: recording at Prairie Sun Recording Studios, Cotati/ USA

Joe Marquez: second engineer at Prairie Sun Recording Studios, Cotati/ USA, boots ("Russian Dance")

Gerd Bessler: recording at Music Factory, Hamburg/ Germany, viola ("Crossroads")

Biff Dawes: mixing at Sunset Sound factory, Hollywood/ USA

Mike Kloster: second engineer at Sunset Sound Factory, Hollywood/ USA

Teresa Jones: production coordinator for Prairie Sun recording sessions

Robert Wilson: album cover concept and art

Christie Rixford: design

Paul Schirnhofer, Ralf Brinkhoff, Herman J., Clarchen Baus: photography

These songs were based on the play 'Black Rider' with Robert Wilson and William S. Burroughs. Some songs were recorded and worked on before the play was performed originally in March 1990 and some about four years later in California (using the same styles and techniques).

Black Rider Liner Notes

When I was first approached by Robert Wilson and the Thalia Theatre of Hamburg to be involved with The Black Rider, I was intrigued, flattered and scared. The time commitment was extensive and the distance I would have to travel back and forth was a problem, but after a meeting at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, I was convinced this was to be an exciting challenge and the opportunity to work with Robert Wilson and William Burroughs was something I couldn't pass up. I had seen only one Wilson production, "Einstein On The Beach" at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and had been pulled into a dream of such impact and beauty, I was unable to fully return to waking for weeks. Wilson's stage images had allowed me to look through windows into a dusting beauty that changed my eyes and my ears permanently. Wilson is an inventor on a journey of discovery into the deepest parts of the forest of the mind and spirit and his process of working is innocent and respectful. His workshops in

stage one demand from all involved to enter his world and place as much value on the things you bring to it as the things you leave behind. I was nervous about our compatability as his process seems so developed and was in a new country as was working in Hamburg, Germany, the Rainey Streets, church bells and the train station. Surprisingly for me our differences became our strength. Each morning I would bring to rehearsal the songs and music I had worked on the night before at Gerd Bessler's Studio. I had chosen Greg Cohen to collaborate with me on arrangements and shaping the music, selecting an orchestra, collecting sounds and recording crude tapes the night before. Greg is a multi-instrumentalist who I've had the pleasure of working with on the road and in the studio for fifteen years or more. Gerd Bessler's Music Factory was where most of the ideas for the score were born. Gerd Bessler is an extraordinary musician and sound engineer and his experience and background with The Thalia Theatre were invaluable to the work. It was his inexhaustible energy and commitment to spontaneity and adventure at his Music Factory and together we came up with fresh material each night to bring to rehearsal in the morning. Greg Cohen was a fearless collaborator, and helped me grow musically and had an endless supply of ideas with (long hours, cold coffee, hard rolls and no place to lie down). Gerd and Greg and I were the core of the music department in the early stages and we fashioned together tapes in this crude fashion, never imagining they would be released, which gave us all an innocence and a freedom to abandon conventional recording techniques and work under the gun to have something finished to bring to Wilson's carnival each morning. Although included in this collection are other recordings of the material done in California four years later, the

spirit of recording in this fashion with Greg Cohen and Gerd Bessler in Hamburg was the cornerstone of the feeling of the songs. Having Wilson's theatre images to be inspired by for writing and arranging was invaluable to the process and a song- writers dram. The Black Rider Orchestra (The Devil's Rhubato Band) were Hans-Jo rn Brandenenburg, Volker Hemken, Henning Stoll, Christoph Moinian, Dieter Fischer, Jo Bauer, Frank Wulff and Stefan Scha fer. They were all from different backgrounds: some came from a strict classical world, others were discovered playing in the train station and my crude way of working took some getting used to for them and I had to learn a language to communicate with them and still keep

the spontaneity alive. They are heard on a few of the songs in this collection. But recording more with them proved to be difficult with time and distance. They were all heroic in their commitment and contribution and became the pit band I've always dreamed of. In California, perhaps four years later, I formed another orchestra built on the same principles as The Devil's Rhubato Band, same instrumentation to replant the seeds from Hamburg. They are featured on many of the songs: "Lucky Day", "Russian Dance", "Shoot The Moon", "Oily Night", "Gospel Train (Orch)", "Flash Pan Hunter", "The Right Bullets" and "Black Box". The group that was formed in California were all musicians from San Francisco, although we began working from charts, slowly I began to realize that to effectively continue we needed a more crude approach and soon abandoned much of the score and worked from tapes and intuition. All of the players in the "Rhubato West" group were eager to "Frankenstein" the music into something like a beautiful train wreck. We recorded in a cold shed with bad light and no breaks, in order to inject the music with new life. "Gospel Train (Orchestra)" was recorded after a frustrating day of discipline, the piece was barked out like a garage band with the whole orchestra aping like a train going to Hell, it was a thrilling moment for all of us and even the bassoonist wanted to hear the play back. They all are fearless, willing and eager musicians. Together with The Hamburg Orchestra, the group in California and the original recordings done with Greg Cohen and Gerd Bessler, we were trying to find a music that could dream its way into the forest of Wilson's images and be absurd, terrifying and fragile. Three things I hope come across in this collection of songs. The actors in The Thalia Theatre production of The Black Rider were of a caliber I had never seen in my experience; fearless, tireless, insane and capable of going to deep profound places under sometimes difficult circumstances (cold coffee, hard rolls, no place to lay down), they took the songs and brought them to life and the songs brought them to life. I had never worked as a composer who was to remain outside of the performance and teaching them the songs was an education as well as them. They were like old children and amazed me with their willingness and the power of the imagination this collection is me singing but inside each performance are things I learned from their interpretations. William Burroughs, was as solid as a metal desk and his text was the branch this bundle would swing from. His cut up text and open process of finding a language for this story became a river of words for me to draw from in the lyrics for the songs. He brought a wisdom and a voice to the piece that is woven throughout. Somehow this odd collection of people resulted in an exciting piece of theatre that became an enormous success in Hamburg at the Thalia, and has travelled throughout the world and is still running today and it was a privilege to be a part of it.

Tom Waits

Los Angeles, Sept. 1993

THE BLACK RIDER

Black Rider Story Line

Once upon a time there was an old forester who lived with his wife and his daughter. And when it came time for his daughter to marry he chose for her a hunter, for he was getting old and wanted to maintain his legacy. But his daughter was in love with another and sadly he was not a huntsman, he was a clerk and the father would not approve of this union. But the daughter was determined to marry the man she loved so she said to him, "if you can prove your marksmanship as a hunter, my father will allow us to marry".

And so the clerk went out to the forest and he took his rifle and he missed everything he aimed at and only brought back a vulture.

The father disapproved and it seemed hopeless, but the clerk was determined to triumph. So the next time he went to the forest the devil appeared to him and offered him a handful of magic bullets, and with these bullets he could hit all the game he aimed at even with his eyes closed. But the devil warned him that "some of these bullets are for thee and some are for me". And as the wedding day approached, the clerk began to get nervous as there was a shooting contest and he was afraid he needed more magic bullets. Although warned that "the devil's bargain is a fool's bargain". He went to the crossroads and the devil appeared as before and gave him one more magic bullet. On the day of their wedding, the clerk took aim at a wooden dove, and with the devil looking on, the bullet circled the crowd of guests and hit its mark not the wooden dove. But the bride, his only love and the clerk ended up in an insane asylum stark raving mad and joined all the other lunatics in the devil's carnival.

BLACK RIDER, GRAY BUTTERFLY

Black Rider Review

The New Yorker January 10, 1994 pp. 76-80

BY PAUL GRIFFITHS

At the end of November, Robert Wilson had two productions opening almost simultaneously on opposite sides of the Atlantic: a revival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music of, "The Black Rider," the product of his collaboration with Tom Waits, William Burroughts, and the history of German Expressionism, and a new staging at the Opera Bastille, in Paris, of "Madame Butterfly." Six of his productions, including the "Butterfly" are scheduled for next season at the Bastille, and works for Florence and with Phillip Glass are in progress. Hip, hop; hip, hop. This may be normal life for your average stage director, but the whole point about Mr. Wilson used to be that he was not your average stage director. His attempt to make himself into just that---to adapt himself to a pattern of routine and overwork---is presenting a bizarre spectacle of artistic suicide, because what happens when you do too much is that you do too little. Shows get put on, as this "Black Rider" was put on, slackly, without people in the audience being able to feel---as if the force were drilling through their heads---the intense pressure of the director's eyes to vivify each gesture, each move, each shift of an item of decor. For the moment, we've lost what used to distinguish Mr. Wilson's stage vision. I miss the length, too. And why the rush? To give us a restaging of "The Addams Family," and a stage version of Puccinni's melodrama.

{parts about "Madame Butterfly" deleted here}

"The Black Rider" was a different kind of disappointment. In recent years, Mr. Wilson's hectic activity has been divided largely between staging operas in Paris and working with theatre companies in Germany: the Schaubuhne of Berlin and the Thalia Theatre of Hamburg. It was for the Thalia company that he put together "The Black Rider" nearly four years ago, and, more recently, "Alic," also with music and lyrics by Tom Waits. As has become the way of things, Mr. Wilson's productions come to this country only after they've been seen in Europe---and seen widely in the case of "The Black Rider," which the Thalia took to Vienna and Paris, and which the company recorded for Austrian televison. So belatedness may have been partly responsible for the weak effect of the piece at BAM. Vampires? That was 1992.

But I don't think that's the whole dismal story. The thing just didn't seem a very interesting piece. I'm not sure why anyone should have decided, other than for very morbid reasons, that William Burroughs would be the person to rewrite the tale of a young man tricked by the Devil's gift of magic bullets into the shooting of his bride on their wedding day---the tale behind Weber's "Der Freischutz." The lyrics had some wit, wonder and oddity when they tried---as in Mr. Burrough's "That's the way the potato mashes/That's the way the pan flashes/That's the way the market crashes," and so on through other spendidly boneheaded rhymes, or Mr. Waits' striking lines, "November has tied me/To an old dead tree/Get word to April/To rescue me"---but mostly, they didn't try. As for Mr. Waits' music, it's all in the graze and grizzle of his voice. Listening to his recording of the songs, you'd think you were hearing from the next Kurt Weill; as delivered by the Thalia actors, the score sounded like a stickwork of nursery rhymes. It needed, too, a band that could do what Mr. Waits found that the Californian players on his recording could do: "'Frankentein' the music into something like a beautiful train wreck." (The railway imagery goes on, in the recording, in the lumbering weight of the rhythms and the metal-on-metal grate of the sound---qualities that were replaced in the Brooklyn performance by looseness and insipidity.)

The best musical moments at BAM---also the funniest---were those intoned by the reocorded voice of Mr. Burroughs. That was the way the pan flashed. And it flashed only fitfully too, in the stage presentation. One scene recalled the focused bizarreness of Mr. Wison's earlier days: the feeling of people onstage being thoroghly absorbed in what they're doing, and completely unfussed to be doing it in public, for an audience that can't but find it inscrutable---In this key scene of precision mystery, the heroine awoke in a room filled with the bloody carcasses of indistinguishable quadrupeds, with, to the rear, two people dressed as incarnations of Horus, and in front, a lady in an evening gown slowly crossing the stage while making animal noises.

Whoever was responsible for the amplification of those noises---and for the projection and transformation of other vocal sounds throughout the piece---is some kind of genius: Mr. Wilson has the knack of attracting them. Ms. Parmeggiani was again the costume designer, turning her fancy this time toward "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" rather than toward the Noh theatre, but with equally effective results. The problems weren't in the technicalities and the accoutrements, and they weren't essentially in the performances: the actors may have been deficient as clowns and siners, but they offered fiercely clean projection, startling grimaces, and a magnificent collection of muscular dysfunctions. No, what crippled the piece was what had, though so differently, crippled the "Madame Butterfly" production: a central lack of seriousness, a vaunting of style.

In "The Black Rider," there was no subject that the production was betraying or ignoring, but maybe for that reason, Mr. Wilson's betrayal of his own achievements and potentialities was the more melancholy to observe. Items from his previous productions---moving beams and boxes of light, colored spots used to illuminate specific actors or objects, scenes mimed in slow motion (as the whole climactic scene of the marriage-murder was), framework furniture---were dealt onto the stage like cards from a pack of tricks and deceits, their magic mocked by the slickness with which they could be pulled out again. The scene I described above, of meat, gods and a moving lady, wasn't much more than a rehash, seemingly calculated to make Mr. Wilson's admirers, me among them, fill up its vacancy with hope and memory.

For the moment, memory is all we have. Only the odd blurry photograph and library videotape appear to survive to represent Mr. Wilson's great works of the early seventies. The videotape of the prologue to the fourth act of "Deafman Glance" was made in 1981, more than a decade after the original piece, and it's a glacial entombment. But hope can persist. In a recent interview in a French magazine, Mr. Wilson gave a hint of being jaded with international success, and of wanting to devote more time to his projects with students in Water Mill, on Long Island. We'll see.

Paul Griffiths

January 10, 1994

The Black Rider

Oberlin College Review

Preliminary "review" of The Black Rider for the Oberlin College Review

Germany has had a problem with its artistic expressions. The second world war created damaging associations. In a recent article, German musician Blixa Bargeld of the band Einsterzend Neaubauten said "That culture which existed before the war is rightly forbidden to us, because of what it lead to--or at best, did not prevent. The point I am trying to make is that the German tradition is gone. We hate our culture and our language. We cannot redeem that tradition." William Burroughs, Tom Waits, and Robert Wilson have tapped into that tradition, pulled out two centuries worth of art, and created the opera "The Black Rider: The Casting of the Magic Bullets". First premiered in Germany in 1990 by the Thalia Theater of Hamburg, Germany, "The Black Rider" draws initially from the story "Der Freischutz", written by August Apel and Friedrich Laun in 1810, based on a 17th century ghost story about a young couple in love and to win over the fiancee's heart, the young man must prove himself as a capable marksmen. A feat the clerk can only succeed with the help of some magic bullets, crafted and tested by the devil himself. Within several years "Der Freischuts" was turned into an opera by the romantic German composer Baron Karl Maria Von Weber.

The recent version, which was first performed in the states at the Brooklyn Academy of Music during Thanksgiving day weekend, was started when Robert Wilson discovered the story and wanted to do an adaptation of it. Robert Wilson started out as a choreographer, painter and set designer. In his work, though, these jobs are really one and the same, because either the people in most of his performances seem like mobile props (especially when they are physically involved with the set, carrying large puppets and such) or his actual sets and use of lights become the center of action. Wilson's works are often long and very slow moving, but his visuals work very well with music. Usually he comes up with the base idea, maybe some sketches and the musicians and he build from that idea. He has worked with artists ranging from David Byrne to Hans Peter Kuhn. His most famous opera Einstein on the Beach, with music by Philip Glass. This five hour piece, which premiered in 1976, turned musical theater and opera on their heads and gave rise to other works that would seem not to fit in the genre of opera, such as The Cave by Steve Reich and Beryl Kerot, Njinga the Queen King by Ione and Pauline Oliveros,(last minute note..someone on post-classical brought Oliveros up and i forgot to mention this) and The Black Rider itself. To provide music and lyrics for The Black Rider, Robert Wilson picked Tom Waits who had done the music to the Jim Jarmusch films Down By Law and Mystery Train. This time he didn't just add music to the visuals, but created much of the story with his lyrics. To flesh it out, Wilson and Waits invited author William Burroughs to write the libretto, adding humor, autobiographical in jokes, and helping along the analogy of the magic bullets and drugs.

Using Der Freischuts as a starting point, they created an opera that draws from German culture throughout. When, in the prologue, the character of Pegleg presents the Company, they each walk out with a distinct musical phrasing and physical gesture. These gestures and musical passages act sort of like Wagnerian leit motifs as they appear throughout the performance. This modern type of musical theater doesn't always stress a linear narrative, or the importance of any one thing over the other. This is shown in scenes where the characters' movements, somewhere between dance and elaborate slapstick; through the set and settings, which frame and become part of the picture; and the music, which isn't stressed as being the main attraction. These features have often been referred to as modern examples of Wagner's gesamtkunstwerk. The performance makes constant references to German Romantic Operas, from Weber to Wagner, not only in the themes and techniques, but also in musical quotes. The opera mixes this with aspects of the performance borrowed from later German art, though seemingly only pre-war. The jagged bizarre sets, dream sequences, stark lighting and chiaroscuro make-up on the actors reminds one immediately of German Expressionism and Surrealism. The set and the make up may have been borrowed from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the classic German silent film. When, after the introductions, Pegleg walks across the stage, dressed all in black, with tails on his jacket and slicked back hair and white make up and sings "Come on along with the Black Rider, we'll have a gay old time," you can see Joel Gray, the master of ceremonies of the play Cabaret introducing his dancing girls to a club full of people ignoring the Nazi's eminent rise to power.

The Black Rider was a fascinating event. Considering the unorthodoxy of Tom Waits songs and orchestration for the small ensemble of assorted instruments ranging from metal saw to e-mu emax sampler. The music sounded like a cabaret being presented in a southern juke parlor. The singing ranged form the aforementioned cabaret to operatic. The texts, the story and the action were a puzzle, the pieces being the actions of the main characters, their dreams, fragments of even older fairy tales and seemingly unrelated monologues. This made the first couple of scenes a little difficult to follow, but constant referral to the synopsis provided, helped quite a bit. (The play was mostly in German except for random words). Luckily, the opera had supertitles, a large rectangular screen above the stage that provided the audience with the translated dialogue, which was obviously helpful but sometimes distracting from the action. The sets were mostly abstract, using colorful lights and neon lights shining on and surrounded by harsh (i have no idea what belonged here, make up your own sequitor) magical bullets that lead straight to the Devil's work ("just like marywanna leads to heroin," in Burroughs' words). The humor in this dark tale comes from its ironies and absurd situations. When Wilhelm, the young lover, goes out hunting with the magic bullets and is successful, he fills the house of his lover, Kathchen, with literally dozens of bloody dead animal carcasses. When Kathchen's father, Bertram, sees the bloody mess, he's so happy with Wilhelm that he's willing to let Kathchen marry him and at this point the three of them, Bertram, his wife and Kathchen's maid all put themselves in the skin of the carcasses and sing a merry song while dancing. Later, Kathchen's uncle speaks a lengthy monologue in English about Earnest Hemmingway's selling of the rights to "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" to a Hollywood producer. This movie deal is seen as a faustian bargain. Wilhelm made a pact with the devil to get his magic bullets (at a neon crossroads, no less) and this won the acceptance of his new father's love, but of course, also caused tragedy.

Robert Wilson's abstract staging and character directions are impossible to date. There are no "historic" buildings in the Black Rider, just squares and lights. The costumes were the same, belonging to no period one would recognize. The brilliant music, which mixes cabaret with jug band blues, and the text, which makes references to the twentieth century even though the story seems considerably older, gives "The Black Rider" a timeless quality, covering timeless themes, mainly dependence, whether on drugs, on other people's acceptance, magic bullets, or the devil. These themes are presented beautifully through the careful synchronization of music, text, movement, and space.

SDS0564@ocvaxa.cc.oberlin.edu

February 18, 1994