|

|

|

01 |

Praise the Lord, O Jerusalem! |

|

|

|

09:37 |

|

|

02 |

O Lord, rebuke me not |

|

|

|

08:25 |

|

|

03 |

Save me, O God! |

|

|

|

04:39 |

|

|

04 |

Why do the heathen so furiously rage? |

|

|

|

12:22 |

|

|

05 |

Praise the Lord, O my soul |

|

|

|

11:13 |

|

|

|

| Cat. Number |

190233 |

| Packaging |

Jewel Case |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

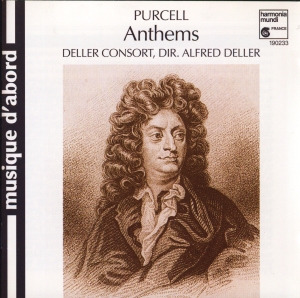

PURCELL o VERSE ANTHEMS

For most of his life Henry Purcell was actively connected with the music of the Church of England. As a boy he was one of the twelve choristers of the Chapel Royal, and at the early age of nineteen he was appointed organist of Westminster Abbey, a post which he held until his death. In 1682, following in the footsteps of his father and uncle before him, he became a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal ; he was appointed as one of the three organists of the Chapel, all of whom were expected to sing in the choir when not performing their duties at the organ. He took part in two coronations, those of James II and William and Mary. At the second of these he seems to have got into trouble with the Dean and Chapter of Westminster for failing to hand over to them the money which he had collected from selling seats in the organ loft. He was threatened with suspension from his post of organist if he did not immediately pay the money over. Purcell complied with this order, and all was well again. This seems to be the only unpleasant incident between Purcell and the clergy, in fact his relations with them appear to have been unusually free from discord when one considers the distrust which so often existed between clergy and musicians in English cathedral foundations. It was not unnatural, since he was so closely connected with the church, that Purcell should write music for it. The Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England makes one important mention of music in its rubrics. At a certain point in the daily offices of Matins and Evensong there occur the words : In Quires and places where they sing, here followeth the Anthem. About sixty-nine of Purcell's anthems have survived but they are badly neglected in English cathedrals today. There are several reasons for this ; one is the relatively small part allotted to the full choir in so many of them. Purcell wrote very few "Full" anthems, and most of those are early works ; by far his greatest contribution to church music was his development of the "Verse" anthem, in which solo voices, or groups of solo voices are used, with the full choir playing a subordinate part - sometimes not appearing until the very end of the anthem. Another feature which precludes modern performance in churches is Purcell's frequent use of a string orchestra ; his string writing does not transfer happily to the organ, and few churches today can maintain a string orchestra ! King Charles II, however, did do just that. When he was invited back from his exile in France in 1660 he instituted an orchestra of "twenty-four violins" (in imitation of the Vingt-quatre violons du Roi of Louis XIV). Although the use of violins in the royal service was not new, this orchestra was more elaborate and ambitious than anything that had come before. It was first introduced into the Chapel Royal in 1662. The diarist John Evelyn records the event thus : "...a concert of 24 violins between every pause, after the French fantastical light way, better suiting a tavern or playhouse than a church". Conservative English taste was shocked by what it considered to be a French importation (and therefore frivolous), nevertheless Charles continued to demand this kind of music from his composers, and his composers continued to supply it; it is difficult to understand how the anthems of Pelham Humfrey could be considered frivolous, for they are mostly tinged with a kind of pathetic melancholy. The anthems of John Blow sometimes erred in the direction of an originality which was not always successful. Purcell studied with both these composers, and he obviously learned much from them as well as improving upon them. The bulk of Purcell's church music belongs to the reigns of Charles II and James II. During the reign of William and Mary, when he was at the height of his powers as a composer, he wrote less than half-a-dozen anthems including, though, the wonderful setting of "Thou knowest Lord the secrets of our hearts". He wrote this for the funeral of Queen Mary at Westminster Abbey on 5th March 1695 ; a few months later it was sung again at his own funeral.

On this record you can hear five Verse Anthems by Henry Purcell. Three of these are for voices and strings, two for voices and organ. Although Evelyn implied that all twenty-four strings played in the Chapel Royal when he was there (see above), we know that at a later date a system was introduced whereby only a few of the players served at a time. This seems to have varied from between five to twelve players. In this recording we have used seven string players and an organ continue, with a chorus of fourteen singers. Most of Purcell's anthems have texts taken from the Book of Psalms. Of the three anthems with strings, Praise the Lord, O Jerusalem was probably written for a special occasion at the Chapel Royal. The words are culled from a variety of sources, which would suggest a compilation for a specific celebration. The date of composition is about 1688. Five solo voices are used, though they mostly sing as an ensemble contrasting with the large five-part choir. Why do the heathen so furiously rage ? is a setting of Psalm 2. It is almost entirely written for the three solo voices, counter-tenor, tenor and bass. The chorus only enters at the end. This was a favourite distribution of soloists in English church music of this period, and of the following century. The counter-tenor and tenor soloists are usually paired, possibly in duets, or else moving together in thirds in the trio sections. The bass has a more widely ranging part and more prominence as a soloist. Praise the Lord, O my soulis a setting of verses from Psalm 103. Six soloists are used, with a four-part choir entering only at the very end. Notable features are the richness of the six-part writing, the expressive trio "The Lord is full of compassion" and the bass solo "For look how high the heaven is". Of the two anthems with organ accompaniment, O Lord rebuke me not is a duet for two sopranos. The text is taken from verses of Psalm 6. There are two interjections by the choir, both identical and both echoing material sung by the soloists. Save me O God is a setting of verses from Psalm 54 for a group of five soloists and a six-part choir.

MAURICE BEVAN