|

|

|

01 |

Incipit Lamentatio Hieremiae Prophetae (Premiere Lecon) |

|

|

|

00:42 |

|

|

02 |

Aleph. Quomodo sedet sola (Premiere Lecon) |

|

|

|

02:35 |

|

|

03 |

Beth. Plorans ploravit in nocte (Premiere Lecon) |

|

|

|

04:11 |

|

|

04 |

Ghimel. Migravit Juda propter afflictionem (Premiere Lecon) |

|

|

|

02:02 |

|

|

05 |

Daleth. Viae Sion lugent (Premiere Lecon) |

|

|

|

03:01 |

|

|

06 |

He. Facti sunt hostes ejus in capite (Premiere Lecon) |

|

|

|

03:26 |

|

|

07 |

Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum. (Premiere Lecon) |

|

|

|

03:32 |

|

|

08 |

Vau. (Deuxieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

00:39 |

|

|

09 |

Et egressus est a filia Sion (Deuxieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

01:39 |

|

|

10 |

Zain. Recordata est Jerusalem (Deuxieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

03:19 |

|

|

11 |

Heth. Peccatum peccavit Jerusalem (Deuxieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

05:14 |

|

|

12 |

Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum. (Deuxieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

02:30 |

|

|

13 |

Jod. (Troisieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

00:37 |

|

|

14 |

Manum suam misit hostis (Troisieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

04:02 |

|

|

15 |

O vos omnes qui transitis (Troisieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

02:11 |

|

|

16 |

Mem. (Troisieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

01:09 |

|

|

17 |

De excelso misit ignem (Troisieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

03:02 |

|

|

18 |

Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum. (Troisieme Lecon) |

|

|

|

02:10 |

|

|

|

| Country |

United Kingdom |

| Cat. Number |

195210 |

| Packaging |

Jewel Case |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

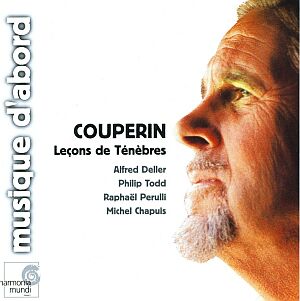

| Countertenor |

Alfred Deller |

| Tenor |

Philip Todd |

| Viola da gamba |

Raphael Perulli |

| Organ |

Michel Chapius |

|

|

Harmonia Mundi HMA 195210

Couperin

Lessons for Tenebrae

From the time he took up his function as organist of the Chapel Royal in 1693, Couperin had written some 20 motets, in most cases for solo voice or small choir: contrarily to Lully or Delalande -who prefered to use great choral masses - Couperin seemed to favour, in his sacred as well as his other pieces, a more intimate kind of music, without specializing in it. The musical language of the Lecons de Tenebres is made up of several types of writing. Gregorian tradition, French style and Italian influences are also present. The Gregorian melody, widely used throughout the entire Middle Ages is still alive today. But, as early as the 15th century numerous composers were attracted by the grandeur and pathos of the Lamentations of Jeremiah. However, throughout almost every version, certain plainsong themes have persisted, mainly in the titles and vocalise. The French style is only displayed in some passages, such as the beginning of the first Lesson's last verse (from Facti sunt hastes to iniquitatum ejus); it is not even possible to isolate an entire verse. But what is more characteristic of the style are the numerous, extremely varied and often highly complex ornaments, such as vocal tremolos on a single syllable, endowing the melody with a special kind of expressive flexibility. The Italian style is mostly used to highlight the expressive quality of the text; this process, frequently used by the composers of madrigals, oratorios and cantatas was introduced in France towards the end of the 17th century, and it appears here much in the same way as it was to appear in most of Bach's cantatas. In the first Lesson, the tears running down the cheeks correspond to a slowly, almost hesitantly, descending melody. There are numerous similar expressive examples throughout the work.

Apart from these examples, the Italian influence is also apparent in daring harmonies, superimpositions and unexpected alterations producing abrupt changes of tonality. The necessity of following the sacred text, of remaining faithful to its spirit, of utilizing only a few voices and instruments, deprived the composer of many of the means usually employed to provide variety to a work and give it sustained interest; and these limitations were likely to create monotony. But Couperin knew how to avoid this. The alternation of vocalization on the Hebraic letters and of the text itself provided him with the opportunity of opposing two kinds of melodies: one in which the voice - devoid of any expressive intention - is used as a kind of wind instrument displaying its technical possibilities and

virtuosity; the other in which the voice is used as a means or highlighting the very words - even syllables - of the text.

There are few works which, with such deliberately limited means, are so full of pathos. The melancholic genius of Couperin was fully in tune with a text of lamentations. This composer who, shortly before the end of his life, was to write uPompefunebre in his Suites for viols, found his natural expression in the Jeremiah text. His music, dramatic and pliable like that of Monteverdi, full of intimate and lyrical fervour, was an ideal vehicle to express the anguish of mortal man and the faith of the Christian soul in eternal life.