|

|

|

01 |

Choros No. 1 (Typico) |

|

|

|

04:49 |

|

|

02 |

Suite Populaire Bresilienne: No. 1 Mazurka - Choros |

|

|

|

03:33 |

|

|

03 |

Suite Populaire Bresilienne: No. 2 Schottisch - Choros |

|

|

|

03:35 |

|

|

04 |

Suite Populaire Bresilienne: No. 3 Valsa - Choros |

|

|

|

04:26 |

|

|

05 |

Suite Populaire Bresilienne: No. 4 Gavota - Choros |

|

|

|

05:20 |

|

|

06 |

Suite Populaire Bresilienne: No. 2 Chorinho |

|

|

|

04:37 |

|

|

07 |

Etude 1 - Allegro no troppo |

|

|

|

01:55 |

|

|

08 |

Etude 2 - Allegro |

|

|

|

01:22 |

|

|

09 |

Etude 3 - Allegro moderato |

|

|

|

02:07 |

|

|

10 |

Etude 4 - Un peu modere |

|

|

|

03:14 |

|

|

11 |

Etude 5 - Andantino |

|

|

|

01:56 |

|

|

12 |

Etude 6 - Poco Allegro |

|

|

|

01:36 |

|

|

13 |

Etude 7 - Tres anime |

|

|

|

02:15 |

|

|

14 |

Etude 8 - Modere |

|

|

|

02:52 |

|

|

15 |

Etude 9 - Tres peu anime |

|

|

|

02:57 |

|

|

16 |

Etude 10 - Tres anime |

|

|

|

01:54 |

|

|

17 |

Etude 11 - Lent - Anime |

|

|

|

03:50 |

|

|

18 |

Etude 12 - Anime |

|

|

|

02:23 |

|

|

19 |

Prelude No. 1 in E minor |

|

|

|

04:23 |

|

|

20 |

Prelude No. 2 in E major |

|

|

|

02:40 |

|

|

21 |

Prelude No. 3 in A minor |

|

|

|

03:05 |

|

|

22 |

Prelude No. 4 in E minor |

|

|

|

03:23 |

|

|

23 |

Prelude No. 5 in D major |

|

|

|

03:19 |

|

|

|

| Country |

Canada |

| Original Release Date |

2000 |

| Cat. Number |

8.553987 |

| Packaging |

Jewel Case |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

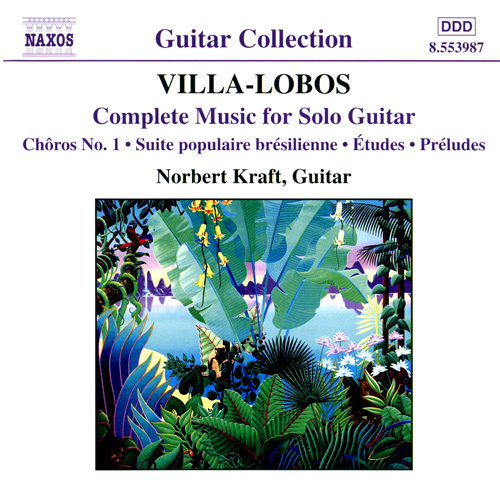

- Choros No.1 (Typico) - Suite Populaire Bresilienne - 12 Etudes - 5 Preludes Norber Kraft, Guitar

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959)

Complete Music for Solo Guitar

Choros No. 1; Suite populaire bresilienne; Etudes; Preludes

Though there are barely forty guitar pieces amongst the thousand or so works contained in Villa-Lobos's catalogue, they would have been enough, by reason of their exceptional quality, to make him one of the most important composers of guitar music of the 20th century. They are the result of a centuries-old inheritance together with personal compositional principles open to progress.

Whether Indian, White or Black, the peoples that make up Brazil have always been musicians. Brought by the Jesuits and the colonizers, the guitar very quickly became a favourite instrument in the country, in popular as well as classical music. In Villa-Lobos's time, European themes were mixed with the country's folk music. In his native Rio, the composer would play together with street musicians and became an excellent guitarist, accompanying the small instrumental groups which improvised on fashionable themes in the "Choros" form, and with the "seresteiros" (serenaders). "We made a logical, not scholarly, counterpoint, far superior to any classical counterpoint", the composer said later, with his characteristic malice. Amongst the forms which he cultivated, the "Suite popular brasileira" (1908-12) immortalizes the improvisations in question in their relative rhythmic simplicity. Thence the subtitles of the four first pieces: mazurka, schottisch (a kind of polka very much in vogue during the 19th century), waltz, gavotte. The last piece, "chorinho", is a miniature choros.

Many explanations of the term "Choros" have been given. Villa-Lobos explained that the Brazilian is "very sentimental, not romantic, and that the term in question came from the Portuguese verb "chorar", meaning "to cry". For Turibio Santos, this crying may also be found in vibrato on the upper strings of the instrument. The "Choros No 1" from 1920 forms the portico of a series of fourteen compositions employing the same title (always in the plural). Conceived for different groups, they culminate with orchestra and choir. The first in the series is symbolic. Dedicated to Ernesto Nazareth, it is inspired by the melodic formulations of these musicians, and its rondo form is in the same spirit. The Parisian years, from 1923 onwards, were an unprecedented period of afirmation which placed him in the first rank of the avant-garde. It was in 1929 that he wrote the Twelve Etudes. Here it is worthwhile making a detour back to the composer's youth. On the death of his father, who had given Villa-Lobos his first musical training, his mother wanted him to become a doctor. As she had confiscated all his musical materials, he was obliged to work in secret, to work out on the guitar pieces by Haydn, Bach and Chopin. In this way he developed a special guitar technique. At the time, Andres Segovia found the Etudes unplayable, but after he had assimilated them the great guitarist recognized that Villa-Lobos had a deep knowledge of the instrument, "If he chose a particular fingering for the performance of a phrase, we should follow his indications, even at the cost of great technical effort, Villa-Lobos has presented the history of the guitar with the fruits of his talent, as great as that of Scarlatti or Chopin." It was in 1953, when they were published, that the composer finally dedicated the etudes to Segovia. Assuredly, they are in themselves a veritable catalogue of innovations, of strange effects in their use of styles ranging from black incantations to the modinha (a Luso-Brazilian sentimental song), in a great variety of rhythms. On the other hand, the compositional basis is close to Chopin, who, as Eero Tarasti has written, had increased in his etudes the technical and sonic possibilities of the piano. The three first are devoted to different ways of playing in arpeggios – the first evokes the playing of a guitarist in a choros ensemble; the fifth explores the polyphonic possibilities of the instrument. The seventh is innovative in various technical ways, which is also the case with the eighth, with its dramatic contrasts. While the ninth adopts the variation principle, the tenth is more complex by virtue of its use of polyrhythms. Generally considered as being highly Brazilian in character, the eleventh, one of the most attractive and evocative, is the peak of the series. The twelfth contains dazzling glissando effects.

Dedicated to Mindinha (Arminda, the composer's second wife), the Five Preludes of 1940 form a highly attractive collection in the richness of their inspiration. Turibio Santos has pointed out the use in these pieces of procedures typical of Joao Pernambuco, one of Villa-Lobos's colleagues amongst the popular musicians, whose compositions became fashionable at the beginning of the 1920s. The melancholy of the opening prelude in E minor is contrasted with a highly Brazilian atmosphere. The arpeggiated Prelude in E major depicts the capadocio (rogue) in Bachian style, and owes its popularity to the suggestive atmosphere in the style of the Bachianas Brasileiras and the lyricism of modinhas. The penultimate piece, in E minor, reflects the primitive Indian soul, which haunted Villa-Lobos throughout his life. It is of a dramatic seriousness and intensity. In the slow waltz of the fifth prelude in D major, the composer's malicious wit comes through when he declared that he had thereby rendered "homage to social life, in other words, fashionable, affected young people, frequenting the concerts and theatres of Rio de Janeiro."

Pierre Vidal

English translation: Ivan Moody