|

|

|

01 |

Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne - Countertenor Solo - Largo |

|

|

|

06:55 |

|

|

02 |

Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne - Soprano solo - Andante |

|

|

|

03:00 |

|

|

03 |

Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne - Countertenor and Bass Duet |

|

|

|

02:25 |

|

|

04 |

Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne - Soprano Duet - Andante |

|

|

|

02:47 |

|

|

05 |

Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne - Soprano Duet - Andante |

|

|

|

06:04 |

|

|

06 |

Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne - Bass Solo - Allegro |

|

|

|

02:25 |

|

|

07 |

Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne - Countertenor Solo and double chorus -Allegro |

|

|

|

03:24 |

|

|

08 |

Zadok The Priest |

|

|

|

05:28 |

|

|

09 |

The King Shall Rejoice |

|

|

|

11:47 |

|

|

10 |

Let Thy Hand Be Strengthened |

|

|

|

08:39 |

|

|

|

| Country |

United Kingdom |

| Cat. Number |

08 5045 71 |

| Packaging |

Jewel Case |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

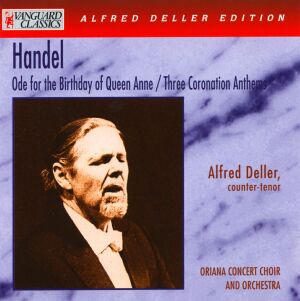

Alfred Deller Edition 1963 / CD reissue - 1995

Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne (Eternal Source of Light Divine), HWV 74

Composition Date - 1713

Composition Description by Brian Robins

The composition of odes to celebrate the new year and the birthday of the monarch was a long standing tradition in England, as a number of works by Purcell and others readily testify. Normally the task of composing such occasional works fell to the Master of the King's (or Queen's) Musick, a position held in the early part of the eighteenth century by John Eccles. However Eccles seems to have provided no such works between 1711 and 1715, a gap filled probably in 1713 for the monarch's birthday by Handel. He had returned to England for a second visit late in 1712, quickly catching the mood of the nation by composing a Te Deum and Jubilate for the service of thanksgiving to celebrate the Peace of Utrecht. It was possibly the success of this piece, the commissioning of which from Handel rather than a native composer has puzzled Handel scholars, which led to him being asked to provide a celebratory ode for the birthday of Queen Anne, February 6. Both the Utrecht Te Deum and the Ode "Eternal Source of Light Divine" demonstrate how clearly he had assimilated the English choral style of Purcell, the sacred work being clearly indebted to the English composer's well-known Te Deum and Jubilate in D of 1694. However Handel's works are planned on a broader scale, with greater prominence given to wind parts. The text by Ambrose Phillips (1674 - 1749) is one of the best examples of a genre that frequently embarrasses modern listeners by its obsequious praise of the subject. Here, however, Handel was provided with a text that not only praises the queen as the author of peace, but includes pastoral imagery of the kind to which Handel always responded with his best music. The result is a seven-movement work that transcends the usual occasional nature of such pieces. Particularly striking are the opening alto solo, with its demanding obbligato part for solo trumpet, the gentle soprano and alto duet "Kind health descends," and the majestic final lines of the chorus, "The day that gave great Anna birth."

Zadok the Priest, coronation anthem No. 1 for chorus & orchestra, HWV 258

Composition Date - 1727

Composition Description by Brian Robins

Zadok the Priest is one of four anthems composed by Handel for the coronation of George II, which took place on October 11, 1727. Handel was commissioned to write the music required for the service because of an interregnum in the post of organist and composer to the Chapel Royal, the incumbent of which traditionally composed the music for such occasions. The event in Westminster Abbey was one of great magnificence and splendor, involving forces larger than Handel had used. They included a chorus of 40 and an orchestra reported to have numbered 160, including trumpets, oboes, bassoons, and timpani. Zadok the Priest, the text of which is taken from the first chapter of 1 Kings in the Old Testament, was the anthem traditionally performed during the Anointing, previous settings including one by Henry Lawes used at the coronations of both Charles II, in 1661, and James II, in 1685. Handel's is a much more elaborate and striking work, dependent for its huge impact on cumulative effect and the great coup de theatre achieved when the chorus' powerful declamatory outburst at the opening words interrupts the extended orchestral introduction. The anthem quickly became by far the most popular of the four, established in the repertoire as simply the Coronation Anthem, and a work performed on nearly every celebratory occasion. In 1784, it took center stage at the massive Handel Commemoration, and its special place in British ceremonial has been underlined by its inclusion in every coronation service since that of George II.

The King Shall Rejoice, coronation anthem No. 2 for chorus & orchestra, HWV260

Composition Date - 1727

Composition Description by Michael Jameson

The British coronation ceremony has survived essentially unaltered for nearly a thousand years, and Handel's four magnificent Coronation Anthems occupy an illustrious place in its history. The most popular of the set, Zadok the Priest, has been performed at every coronation since it was first heard at the 1727 coronation of King George II and Queen Caroline. The King Shall Rejoice (HWV 260) was also written for this same royal occasion and was specifically intended for the part of the service during which the new monarch receives the crown. The King Shall Rejoice takes its texts (almost word for word) from the Book of Psalms (Ps. 21) and is divided into four sections. The opening sequence based on the first stanza of the Psalm leads to a setting of "Exceeding Glad Shall He Be." After this comes a heaven-storming declaration for full choir and orchestra of "Glory and Worship," before the anthem ends with a final, majestic "Alleluia." The scoring gives special prominence to ceremonial clarino trumpets, which add nobility and brilliance to the most opulent moments, as does the use of the organ. Some sources affirm that it was at the insistence of King George himself that Handel provided the anthems for his coronation. However, organist Maurice Greene was senior to Handel in the royal musical establishment and felt that he, rather than a foreigner, should have been accorded the honor. Handel was also offended when several bishops sent him the Biblical texts for the anthems. He resented any inference that he did not know his scriptures well enough to make his own selections and wrote back saying "I have read my Bible very well, and shall choose for myself." Nor, if some who attended are to be believed, was the event itself a complete musical success. Handel himself presided over a vast orchestra of over 150 players, but had a mere 50 or so singers at his disposal. This fact, combined with the reverberant acoustics of London's Westminster Abbey, probably ccasioned Archbishop of Canterbury William Wake's complaint (noted down on his Order of Service) "The anthems in confusion; all irregular in the music." Even so, the occasion was a remarkable patriotic spectacle, and it is easy to appreciate that this impressive music must have left its first hearers awestruck.