|

|

|

01 |

In Tempore Paschali |

|

|

|

18:27 |

|

|

02 |

Regina Caeli |

|

|

|

06:49 |

|

|

03 |

In Assumptione Beatae Mariae Virginis |

|

|

|

16:58 |

|

|

04 |

Ave Regina Caelorum |

|

|

|

04:33 |

|

|

05 |

Salve Regina |

|

|

|

05:04 |

|

|

|

| Country |

USA |

| Cat. Number |

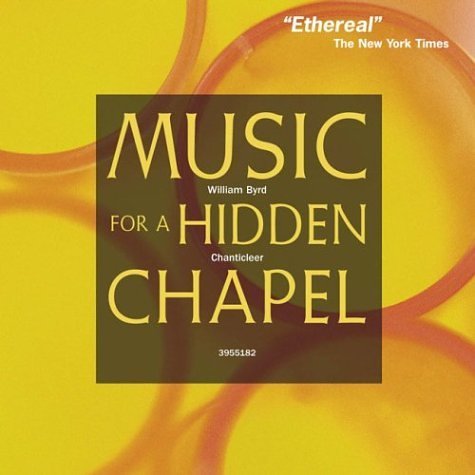

3955182 |

| Packaging |

Jewel Case |

| Spars |

DDD |

| Sound |

Stereo |

|

|

|

Chanticleer

Biography by Corie Stanton Root

Chanticleer may be the only independent full-time classical vocal ensemble in the United States. Since its inception in 1978, the group has developed an excellent reputation for its interpretation of music from many genres, and its bell-like sound has set a new ensemble standard.

Originally founded to sing Renaissance vocal repertoire, Chanticleer has toured worldwide and released more than twenty recordings. While most of Chanticleer's work is done a cappella, the group has collaborated such unusual projects as a fully-staged opera, recordings of jazz standards with the Don Haas Trio, and performances with the unorthodox Japanese dancers Eiko and Koma. Its repertoire ranges from chant to twentieth century pop. In 1978, founder Louis Botto, a graduate student in musicology, was disturbed by the fact that sacred Renaissance vocal music was so rarely performed. So he formed a group to sing this neglected repertoire. Trying to hold to the male-only Renaissance tradition, Botto asked friends who sang with him in the San Francisco Symphony Chorus and Grace Cathedral's Choir of Men and Boys to join the group. Rehearsals began, and the ensemble arranged a debut performance in San Francisco's historic Mission Dolores.

The works chosen for the debut included compositions by Renaissance composers whose music would become staples of the group's repertoire: Byrd, Ockeghem, Morley, Dufay, and Josquin. The members settled on the name Chanticleer in honor of the "clear-singing" rooster in Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, which Charlie Erikson, one of the baritones, was reading at the time. While maintaining its basic repertoire of Renaissance music, Chanticleer also began experimenting with music of other genres. The number of singers varied and eventually settled at 12.

In 1980, the ensemble participated in the Festival of Masses in San Francisco. Robert Shaw was the festival's conductor that year, and after hearing Chanticleer's solo concert proclaimed it "one of the most beautiful musical experiences" of his life. A turning point in Chanticleer's history came when Joseph Jennings, a countertenor, joined the group in 1983. Other members soon recognized his exceptional vocal and interpretive abilities and asked him to become Chanticleer's first music director. Since he accepted that position, Jennings' startling vocal clarity and innovative arrangements have become hallmarks of the ensemble.

International early music audiences began to find out about Chanticleer after a 1984 performance at a large scholarly conference in Belgium. Chanticleer created its own label, Chanticleer Records, releasing a tenth-anniversary CD in 1988. Over the next six years, the ensemble released ten recordings on its private label. These CDs sold well at Chanticleer's concerts, and in 1994 Teldec Classics International signed Chanticleer to an exclusive recording contract. The group's recordings suddenly became available all over North America and abroad. By 1991, Chanticleer was financially able to make all 12 of its members full-time employees, allowing the group to tour more frequently and take on a wide variety of projects. Since then the ensemble has performed and recorded with the London Studio Orchestra, jazz legend George Shearing, and the New York Philharmonic. In 1994, the group presented a critically acclaimed, fully staged performance of Benjamin Britten's opera Curlew River. In 1997 Chanticleer recorded works by Mexican Baroque composers Manuel de Zumaya and Ignacio de Jerusalem with an orchestra of period instruments. It has commissioned works by many of the late twentieth century's foremost composers, including David Conte, Morton Gould, Bernard Rands, and Chen Yi (who served as Chanticleer's composer-in-residence from 1993 to 1996). In 1999, Chanticleer released a collection of these works on its CD Colors of Love.

William Byrd

Send to Friend

Birth

1543 in Lincoln [?], England

Death

Jul 4, 1623 in Stondon Massey, Essex, England

Genre Country

Choral Music

Keyboard Music

Vocal Music

England

Period Years Active

Renaissance 1575-1614

Other Entries Products

Popular Music Entry

Movie Entry

Sheet music

Corrections to this Entry?

Biography by AMG

Even in an era so richly stocked with great names, William Byrd demands particular attention as the most prodigiously talented, prolific, and versatile of his contemporaries. Byrd was born in about 1543, and it is assumed that he was a chorister in the Chapel Royal (his brothers were choristers at St. Paul's Cathedral) and a student of Thomas Tallis. He was named organist and master of choristers of Lincoln Cathedral at the age of 20, where he wrote most of his works in English and music for Anglican services. This music and his anthems provided the young English church with some of its finest music. In 1570 he was appointed a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, where he shared the post of organist with Thomas Tallis. Queen Elizabeth I, despite Byrd's intense commitment to Catholicism, was one of his benefactors, and granted him and Tallis a patent to print music in 1575. Their first publication was a collection of five- to eight-part, Latin motets, but they published little else. Around the same time, Byrd began composing for the virginal. His contribution to the solo keyboard repertoire comprises some 125 pieces, mostly stylized dances or exceptionally inventive sets of variations which inaugurated a golden age of English keyboard composition.

During the 1580s and 1590s, Byrd's Catholicism was the driving motive for his music. As the persecutions of Catholics increased during this period, and occasionally touched on Byrd and his family, he wrote and openly published motets and three masses (one each in three, four, and five parts), which are his finest achievement in sacred music, almost certainly composed for small chapel gatherings of Catholics. Byrd had taken up the publishing business again, printing the first English songbook, Psalmes, Sonets and Songs in 1588. This and his other songbooks include Byrd's compositions in the leading secular genres of the day: the ayre or lute song, the madrigal, and the consort song for solo voice and viols. The consort song's finest hour came at the hands of Byrd, who preferred texts of a high moral (frequently religious) or metaphysical tone. They are notable for the way the viol parts lead an existence independent of the vocal line. He openly published two Gradualia in 1605 and 1607, with music for the Propers of all the major feast days. His last collection, Psalmes, Songs and Sonnets from 1611, consisted mostly of previously published works, but did include two of his viol consort works. Byrd is at his most distinguished in the free fantasias for consort, particularly the later pieces in five and six parts, works of exceptionally luxurious texture. Byrd's last songs were published in 1614, and he lived out his life comfortably at Stondon Massey, where he died in 1623.

Propers for the Mass of Easter Day, for 5 voices (Gradualia, Book 2)

Send to Friend

Composer

William Byrd

Genre

Choral Music

Work Type

Mass Section

Composition Date

1607

Average Duration

18:30

Corrections to this Entry?

Composition Description by Blair Johnston

After achieving a rather restrained musical tone in Book 1 of his Gradualia collection, English composer William Byrd threw open the gates to a more dramatic kind of text/music relationship and, by and large, a more vibrant compositional style for the various Mass Propers contained in Book 2. The Gradualia contains some 110 Latin motets that Byrd combines to form music for the various feasts and celebrations that occur throughout the Catholic year; of all the Masses contained within this massive compilation, the Easter music is widely felt to be the most important-in style, content, and execution it stands with the very best music that William Byrd ever created. Byrd provides five basic sections of music for the Easter Mass: an introit, gradual (and alleluia), sequence, offertory, and communion. Throughout the work Byrd flirts with harmonic and thematic procedures that are quite strikingly modern-circle of fifths motion abounds, and thematic/motivic substance is drawn with crystal clarity. The introit Resurrexi is itself cast in several sections, the main Resurrexi itself, the introit verse Domine probasti me, and the doxology Gloria Patri (the Resurrexi music is to be repeated after the doxology). The opening text of the introit, focusing on the word "resurrexi", is set to a florid, energetic imitation that effectively "paints" the "rising" involved (by means of upward arppeggiation). Something of this same spinning quality spills over into the verse Domine probasti me, an extract from Psalm 138, though here Byrd calls on just three voices. The fourth voice is again allowed to take part in the doxology, during which stronger hints of homophony than any yet heard peek through. The gradual Haec dies and the following alleluia are fused into a single large musical entity. The Haec dies text is drawn from Psalm 117, and each of the four lines of text is given its own small section of music. Byrd sets the opening line in a wholly canonic manner (with the voices in pairs, the fifth and central voice acting as a kind of fulcrum between them); although the canonic structure breaks down by the next line, the imitative interplay continues unabated. After the requisite florid "alleluia" passage, the alleluia verse Pascha nostrum immolatus est Christus is given in striking homophony. The text of the following Victimae paschali laudes is of great length, telling of the struggle between life and death and Christ's triumphant resurrection. Here Byrd employs a far more archaic-sounding style, purely in order to get the text out quickly. A striking duet is given in the third verse, while in the following passage the two sopranos are used to give Mary's answer to the question posed by the entire ensemble. The full ensemble is called back into action for the final triumphant verse. The following piece, Terra tremuit, is, by comparison, very short. After the purely Renaissance Victimae paschali laudes, this two-line offertory is amazingly modern-sounding, even using a striking repeated- semitone figure to draw attention to the important word "tremuit (trembled)"; here we see how closely allied some of Byrd's musical tactics were to the kind of madrigalisms and text-painting then flourishing in Italy. Pascha nostrum, the concluding communion, is almost equally forward-looking. After a single long, imitative phrase on the text "Pascha nostrum immolatus est Christus (Christ the paschal lamb is sacrificed)" a contrasting alleluia passage is inserted. In the second half the voices divide into two halves to give their respective thoughts on the text "sinceritatis et veritatis (bread of sincerity and truth)" before coming together to give the same text in glorious homophony.

Regina coeli, motet for 3 voices (SAT)

Send to Friend

Composer

William Byrd

Genre

Choral Music

Work Type

Renaissance Motet

Composition Date

1605

Average Duration

06:40

Corrections to this Entry?

Composition Description by Blair Johnston

In William Byrd's massive Gradualia collections are contained, in addition to numerous settings of various Mass Propers as needed for feasts and celebrations throughout the year (such as the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary on March 25 or, of course, the Nativity), a number of pieces that do not necessarily fall into a strict categorization but might be employed in a number of ways and at a number of times. Such a work is the three-voice Marian antiphon from the Easter office, Regina coeli, published in the first book of Gradualia in 1605. It is thought that most of the Gradualia music was originally intended for use in private ceremonies (Byrd was, after all, living in a Protestant state, and it was only after retiring from active duty with the Royal Chapel that he began to compose music for the Catholic services that he took part in), and, indeed, the intimacy of Regina coeli's three-voice texture and the restraint with which Byrd explores the music/text relationship (the latter a characteristic of many Gradulia pieces) would seem to support such an idea. Although the Regina coeli text is relatively brief, Byrd sets it in an expansive way, devoting an entire section of music to each of the text's four lines and expanding the "alleluias" that appears at the end of each line into four full-blown sections. Thus is born an eight-part structure in which each section is of nearly equal duration—around fourteen or fifteen breves apiece. First comes the text "Regina coeli laetare (Rejoice, Heaven's Queen)", set in a highly melismatic fashion and cadencing, as does the following alleluia, in the home tonal level (within the Dorian context). Byrd chooses to set the two central verses, "quia quem meruisti portare (for he whom you were fit to bear)" and "rexurrit sicut dixit (has risen as foretold)", in a less melodically decorative style; these two portions come to closes a third above and a third below the basic tonal level, respectively. For the final verse, "Ora pro nobis Deum (Pray to God for us)", the florid style of the opening section is recalled, and the half- cadence on which the verse ends is suitably resolved by the following, fourth, alleluia.

WHAT SOUND?

ROBERT HUGILL asks some questions

about the music of William Byrd

What sound do you think of when you listen to the Byrd masses; an English cathedral choir (men and boys with male altos), a more continental choral sound (men and boys with boy altos); a mixed voice choir such as the Tallis scholars; a full choral sound or one voice to a part? More to the point, what sound was Byrd thinking of when he wrote the masses? This has always fascinated me when singing the masses as they do not easily fit a mixed voice SATB choir. In the version of the four-part mass that we sing at Latin Mass at St Mary's Church, Cadogan Street, Chelsea, London, the mass is in A flat, a tone lower than printed. So the bass part stretches up to a high F, the alto part stretches down to low F plus altos and tenors are often required to act as two equal parts, crossing frequently, even though altos are down in their boots and the tenors up at the top of their range. Did Byrd compose with a particular group in mind, or are these simply masses of the mind; music from a genius ignoring the constraints of ordinary performance? Before leaping to too many conclusions, it may be useful to consider some of the historical background to the works.

Byrd was a Roman Catholic in protestant England, with a post at court. But from the 1570s the authorities began to clamp down on Catholics. Like many Catholic families, Byrd probably regarded the attendance of Anglican Church services as necessary, relying on his wife to keep the family honour by remaining devotedly Roman Catholic. From 1577 his wife and family came under scrutiny; Catholic acquaintances came under intense persecution and from 1581 the Byrd household was regarded as suspiciously 'papist'. Byrd came under investigation himself and in 1588 his wife and two daughters were pronounced outlaws. Catholic peers and the Attorney-General intervened on his behalf and finally in 1592 the Queen herself appears to have ordered the authorities to halt their harassment.

During all this, Byrd continued his work at court and continued to publish Latin sacred music. He almost certainly had some sort of immunity from the Queen; a document relating to this is referred to by his son in the next century. To us this all seems very bizarre; as if an American popular entertainer, at the height of the McCarthy prosecutions, was a well known communist but was not prosecuted due to his popularity with the American President.

Byrd, together with Thomas Tallis, had been granted a monopoly on printing music. The two published a volume of Cantiones Sacrae in 1575 and Byrd went on to publish two more volumes in 1589 and 1591. These are substantial works for mainly five-voice vocal ensemble setting Latin texts. Though Byrd set sacred and Biblical texts, these are not liturgical works. There is some indication that liberal Protestants regarded them as a form of vocal chamber music. But we are coming to understand that Byrd's choice of texts was frequently geared up to giving coded messages of support to the Roman Catholics.

By 1593 the strain was obviously beginning to tell and the Byrds moved to a property at Standon in Essex, close to the estates of Lord Petre, a Roman Catholic peer. Even so, between 1592 and 1595 Byrd published his three settings of the ordinary of the mass, the masses for three, four and five voices. Some continental influence is shown as these are some of the earliest English masses to set the Kyrie, generally the English tradition was to use a plainchant Kyrie. It seems incredible that Byrd should have published these masses, at the height of the persecution of Roman Catholics; his only concession was to miss off the title pages. But he needed to publish them to achieve his aim.

The masses can be seen as a gesture of support for the Roman Catholic community; written for performance during Roman Catholic masses. Catholicism survived underground because of the support of the Catholic peers who would provide a mass centre that could be used by their households and the local Roman Catholic community. These mass centres could be in discreet chapels but they could also be in remote barns or out-buildings. Anywhere where a watchful eye could be kept.

It is important, I think, to bear in mind the nature of these underground services. Roman Catholicism in the sixteenth century was not a casual religion; services were not of the form of a group breaking of bread in the way of the twentieth century. The Tridentine rite had only been introduced in the late 1560s and many of the English clergy dated from Mary's reign and would probably have still used the older, more elaborate rite. For those of us used to the twentieth century's rationalising simplifications, it is good to remember that the complex Tridentine rite was itself introduced as a rationalisation and modernisation. The mass as celebrated by English recusants would have consisted of the celebrant silently, privately saying mass, with the responses said only by the Deacon, the congregation acting as generally silent witnesses. Only occasionally, at the ends of prayers would the priest raise his voice to the point of audibility and then the congregation would say/sing the response. There were two major factors in the services, the artefacts needed for the service and for dressing the altar and the provision of music which was sung whilst the priest was inaudibly saying mass. The provision of these two (artefacts and music) would have been a problem for recusant; both were significantly incriminating but difficult to do without. Artefacts had to be hidden when not in use and music required musicians and access to written music.

Music must have been a serious problem for recusants; until the break with Rome and the suppression of chantries and foundations, there would have been a reasonable supply of reference copies of psalters and the like providing the music needed for services. Not just settings of the ordinary, but the copious amounts of plainchant needed to cover all the propers (the introit, gradual, alleluia, offertory, communion and other sentences, all of which change according to the day and festival). Even with musicians with a good memory, services must have started to seem rather barren and bleak under the persecution.

At first the simple survival of the service itself was important, just being at mass was a great source of succour to Catholic individuals. But, just like the Arts in England during World War Two, there was a gradual realisation that it would be desirable that they survive in some, altered format; so we can imagine Catholics privately gradually attempting to restore some elements of visual and aural splendour to the services.

We still have no clear idea of the extent of underground compositions written for use in the recusant community, but Byrd's masses would have been part of this campaign. To be useful they had to be available, hence the necessity to print them, though it is possible that they were circulating in manuscript some years before their publication. And their provision of masses for five, four or three voices was immensely practical in situations where the provision of music was ad hoc.

We know some little about the musical set up of services thanks to some memoirs by a Jesuit priest: he describes saying mass in a remote place, with a choir made up of a few members of the owner's household; a choir of men and women. This is particularly significant as women were, in theory, not allowed to sing in Roman Catholic services (hence the development of high falsettists and castrati).

Gatherings would no doubt have been disguised as routine household celebrations. Without too much artistic licence, we can imagine a group entertaining themselves after a meal by madrigals sung together and the going on to celebrate mass the next morning with the same group of people now singing mass itself.

So here is where we come to the nub of the matter. The masses were written to be useful to a flexible, variable group of adults (and possibly children). All are in keys from which transposition is simple. We can imagine the four-part mass being sung, variably, by a choir made up of women sopranos, with male altos, tenors and basses or women sopranos, women altos and male tenors and basses or even by an all male group. The Cardinall's Music, in their recordings have found that the four-part mass responds well to being transposed down to be sung ATBarB. As it was not usual for women to sing in church, the supply of women willing and able to do this might have been small so we can possibly imagine the masses being frequently sung by women sopranos with men on all the other parts or by all men in the ATBarB format. The three voice mass is even more flexible. It can easily be sung by SAT, ATB or even TBarB and its very shortness must have made it attractive if the mass had to be hurried.

All this helps us to make sense of the Byrd masses. Their origins in English recusant services rather than as part of an established church mean that the masses remain sui generis. We should not lose sight of Byrd's genius: it could be that the masses, though certainly practical, still contain elements that are not quite ideal, elements that arise simply from the composer's skill, and that is part of their charm.

__________________